Recently, I’ve started visiting the cemeteries of my ancestors. Fortunately, most of my maternal ancestors stayed in the Boston area after immigrating, so it hasn’t been too difficult.

Recently, I’ve started visiting the cemeteries of my ancestors. Fortunately, most of my maternal ancestors stayed in the Boston area after immigrating, so it hasn’t been too difficult.

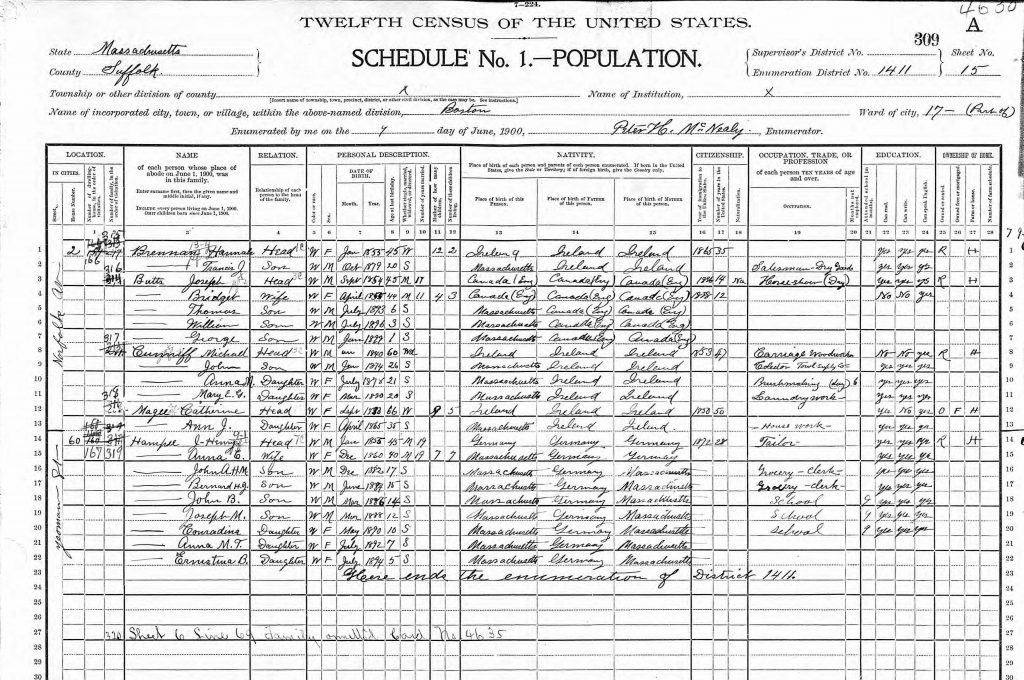

A few months ago, I visited St. Joseph’s Cemetery in West Roxbury in search of the headstone of my great-great-grandparents, John Henry and Anna K. (Ulrich) Hampe. After searching for some time, I finally came to the Hampe plot. Listed on the headstone are John and Anna, as well as their children Joseph M., Bernard J., Anna M., and B. Ernestine Hampe. Though I was happy to take a few pictures, I couldn’t help but feel a flicker of disappointment. With the exception of Joseph, the other Hampes buried at St. Joseph’s Cemetery only list their birth and death year, rather than the full dates of those events. Continue reading Correcting an error