First, a clarification. When I pulled out Richard Newton’s name for the example in my last post, I did not check to see whether he was a Great Migration immigrant. Turns out he is. However, as his Great Migration sketch is not on the horizon, we will continue to pretend he belongs to the Early New England Families Study Project! Continue reading Collecting published accounts: Part Two

First, a clarification. When I pulled out Richard Newton’s name for the example in my last post, I did not check to see whether he was a Great Migration immigrant. Turns out he is. However, as his Great Migration sketch is not on the horizon, we will continue to pretend he belongs to the Early New England Families Study Project! Continue reading Collecting published accounts: Part Two

Category Archives: Genealogical Writing

“Remember your ancestors”

So read the words atop a family record engraved by Richard Brunton in the early 1800s. It is that admonition, which speaks directly to the NEHGS purpose, that led us to have an interest in Brunton – now the subject of a new book written by art historian Deborah M. Child: Soldier, Engraver, Forger: Richard Brunton’s Life on the Fringe in America’s New Republic.

Over the centuries, families have kept records of their history: in pen and ink, in needlework, and now in printed books and in electronic media. Families have kept these “documents” not just as cherished mementos of loved ones, past and present, but also as the “central repository” for the vital records of the family and its members. Richard Brunton – an English soldier who deserted during the American Revolution and made his home in New England – was a trained engraver. During the years when he was traveling throughout New England practicing his craft – sometimes even in the production of counterfeit bank notes – he was, in his own way, at the vanguard of the business of producing family register forms, something that would only increase and become more commercially viable in the following decades. Continue reading “Remember your ancestors”

Writing family history: Start small

Earlier this year, I read a blog post by the New York Public Library titled “20 Reasons Why You Should Write Your Family History.” Always on the lookout for new ideas to work into our seminars and webinars on writing and publishing, I read it eagerly. One particular thing caught my eye: a quote from John Bond’s Story of You, saying, “You are doing a service by leaving a legacy, no matter how small or large.” I’ve thought about that quote a great deal, with a specific focus on the word small.

Earlier this year, I read a blog post by the New York Public Library titled “20 Reasons Why You Should Write Your Family History.” Always on the lookout for new ideas to work into our seminars and webinars on writing and publishing, I read it eagerly. One particular thing caught my eye: a quote from John Bond’s Story of You, saying, “You are doing a service by leaving a legacy, no matter how small or large.” I’ve thought about that quote a great deal, with a specific focus on the word small.

Starting small is great advice for the family historian looking to write and publish. I’ve spoken with many people who struggle with just how to get started. They might have years’ worth of data, in paper files and electronic files. How should they organize it? What should be their focus? It seems such a daunting task that they simply can’t get going – or can’t complete what they’ve set out to do. Continue reading Writing family history: Start small

Collecting published accounts

This may turn out like watching sausage being made or paint dry, but let’s walk through the process of creating an Early New England Families Study Project entry.

This may turn out like watching sausage being made or paint dry, but let’s walk through the process of creating an Early New England Families Study Project entry.

We start with the entry from Torrey’s New England Marriages Prior to 1700:

NEWTON, Richard (–1701) & Anne/Hannah? [LOKER/ RIDDLESDALE] (ca 1616–1697); by 1641; Sudbury {Stevens-Miller 132, 138, 143; Marston-Weaver 47; Warner-Harrington 414, 471; Reg. 49:341; Bullard Anc. 153; Chaffee (1911) 134; Holman Ms: Loker 3; Moore Anc. 399; Framingham Hist. 340, 342?; Marlboro Hist. 421; Bent Anc. 27; Newton (#4) 17-18; Bigelow-Howe 94; Leonard (#2) 49; Cutler 2:5; Morris-Flynt 56; Tingley-Meyers 92} Continue reading Collecting published accounts

First Settlers of Connecticut

Other than Vermont, the five New England states had significant European-derived settlements in the early colonial period. In late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, “genealogical dictionaries” were produced for the states of Rhode Island,[1] Massachusetts,[2] and Maine and New Hampshire (together).[3] Such a dictionary was not completed for Connecticut, but Royal Ralph Hinman had made an earlier attempt in the mid-nineteenth century which can serve as an initial reference when researching seventeenth-century families of Connecticut. Continue reading First Settlers of Connecticut

Other than Vermont, the five New England states had significant European-derived settlements in the early colonial period. In late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, “genealogical dictionaries” were produced for the states of Rhode Island,[1] Massachusetts,[2] and Maine and New Hampshire (together).[3] Such a dictionary was not completed for Connecticut, but Royal Ralph Hinman had made an earlier attempt in the mid-nineteenth century which can serve as an initial reference when researching seventeenth-century families of Connecticut. Continue reading First Settlers of Connecticut

Verify what? Part Two

Collect and compare as many different published versions of the subject as you can. Often there is one old surname genealogy and/or a “dictionary” of settlers. Then there will be some accounts of different branches in some “all-my-ancestors” volumes (often seen in Torrey’s New England Marriages Prior to 1700 – see the new version of Torrey on americanancestors.org that now takes you to the image of the full page from the book, allowing you to see and print all of the entries with the same surname together.) Continue reading Verify what? Part Two

Collect and compare as many different published versions of the subject as you can. Often there is one old surname genealogy and/or a “dictionary” of settlers. Then there will be some accounts of different branches in some “all-my-ancestors” volumes (often seen in Torrey’s New England Marriages Prior to 1700 – see the new version of Torrey on americanancestors.org that now takes you to the image of the full page from the book, allowing you to see and print all of the entries with the same surname together.) Continue reading Verify what? Part Two

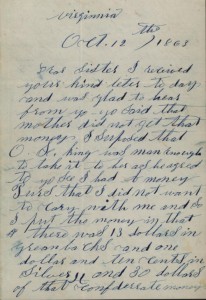

Something to love in Civil War pensions

Following up on my post last month regarding Revolutionary War pensions that can have troves of information, I remembered another subsection within Civil War pensions that are almost always filled with immense amounts of genealogical and biographical data. These are the “Parents’ Pensions.”

While most of us are probably familiar with veterans’ and widows’ pensions, the parents’ pension was claimed by one or both of the parents of a deceased Civil War soldier. The pension act of 27 July 1868 stated: Continue reading Something to love in Civil War pensions

Verify what?

There appears to be a bit of trepidation among new researchers about what is meant by “verifying” sources. It probably sounds horrendously difficult, time consuming, and redundant, but it doesn’t have to be as hard as some would think – and any time spent spent “auditing” sources can return great benefits. Here are a few pointers.

There appears to be a bit of trepidation among new researchers about what is meant by “verifying” sources. It probably sounds horrendously difficult, time consuming, and redundant, but it doesn’t have to be as hard as some would think – and any time spent spent “auditing” sources can return great benefits. Here are a few pointers.

When assessing whether a source, or part of a source, needs verifying, consider the following: Continue reading Verify what?

Trust but verify – again

What is it with these genealogists? They’ve been researching for hundreds of years, published thousands of books and magazines, and still can’t get it right! In my last post, we left off with the question, “Can we trust nothing? must we verify everything from scratch?”

What is it with these genealogists? They’ve been researching for hundreds of years, published thousands of books and magazines, and still can’t get it right! In my last post, we left off with the question, “Can we trust nothing? must we verify everything from scratch?”

The answer is no, you don’t have to verify everything – but it is usually a good idea to verify whatever you can. Those who love the hunt and enjoy being genealogical vigilantes don’t mind this little quirk about our “pastime,” but it can certainly be confusing to newcomers, especially the millions being courted today with advertisements of “easy” genealogy. Continue reading Trust but verify – again

The 1920s, the ’20s, the twenties: writing dates

A few months ago, we agreed that apostrophes do not belong in plurals: To make a plural, generally you add an s or es. No apostrophe. The same rule applies when you are referring to a decade, say, the 1920s. It is absolutely fine to put a letter after a number without an apostrophe between.

A few months ago, we agreed that apostrophes do not belong in plurals: To make a plural, generally you add an s or es. No apostrophe. The same rule applies when you are referring to a decade, say, the 1920s. It is absolutely fine to put a letter after a number without an apostrophe between.

If, however, you decide to drop the 19 from 1920s, you would insert an apostrophe to show that something is missing: the ’20s. (After all, that is one of the apostrophe’s jobs: to show that something has been removed.)

You could also spell out the abbreviated form as “the twenties,” keeping it lower case unless you are talking about the Roaring Twenties, a distinct historic era. The Chicago Manual of Style,[1] NEHGS’s style guide of choice, says, “Decades are either spelled out (as long as the century is clear) and lowercased or expressed in numerals.” I’ll repeat: As long as the century is clear. In genealogical writing, we’re often discussing such long spans of time, and precision is so essential, that we will probably always want to use the form 1920s, to distinguish the twenties decade from the 1820s or the 1720s or the 1620s—and soon from the 2020s.

Here are some other basic guidelines for writing dates: Continue reading The 1920s, the ’20s, the twenties: writing dates