One of the most thoughtful gifts my son has ever given me is a small, black journal with blank pages which I carry with me every day. Kevin’s instructions to me at the time were to write down my memories as well as my family’s memories and stories. His good intentions became my inspiration and abiding interest, my focus in my family history research, and my obligation. Scribbling madly, I started asking for stories to preserve for our following generations.

One of the most thoughtful gifts my son has ever given me is a small, black journal with blank pages which I carry with me every day. Kevin’s instructions to me at the time were to write down my memories as well as my family’s memories and stories. His good intentions became my inspiration and abiding interest, my focus in my family history research, and my obligation. Scribbling madly, I started asking for stories to preserve for our following generations.

I soon understood that there is a significant difference between stories and memories. Memories are the foundation and basis for the stories they may become as time puts them in a different context. While some are skeletons in the making, our family stories give us a better understanding of our ancestors’ characters and their perspectives on their world, as well as some insight into their actions and motivations.

One story about my great-grandmother Felicia Libby Lee (1854–1952) grew from my grandmother Winifred’s memory of a traumatic day when she and her three siblings were little. The older menfolk went off one August for several days on a cattle drive, leaving Felicia alone with the children on their remote Kansas farm. An unfortunate battle with a rattlesnake left her bitten. She treated the wound, and, fearing that she might die, fired up the wood stove to cook enough food to keep the children alive until their father returned. In the prairie heat, with the wood stove roasting everything near it, Felicia sweated out the venom and was there to greet the returning family.

My maternal cousin, Ellie Bailey, offered one story about how our McLeod grandmother refused to ever wear anything purple. Grandmother Lula Roberts McLeod looked down on the large McLeod family for their Canadian log cabin origins, and did not like Frances, her mother-in-law. When Frances died, she was embalmed and dressed in purple in an open casket. The embalming fluid leaked through her dress. Standing next to the coffin, Lula was revolted so much that she refused to ever wear purple again.

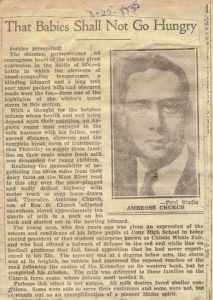

It was a newspaper clipping (shown above) that gave me some insight into my father, Ambrose S. Church (1912–1995), a man not inclined to brag or to compliment himself. The newspaper article told how, during a blizzard, Dad, a dairy farmer, had strapped on snowshoes and a backpack loaded with bottles of milk to deliver to families with infants. Nor had he ever told me he had served as a city councilman – that he never mentioned having grown a feeble mustache (barely visible at right) is understandable.

It was a newspaper clipping (shown above) that gave me some insight into my father, Ambrose S. Church (1912–1995), a man not inclined to brag or to compliment himself. The newspaper article told how, during a blizzard, Dad, a dairy farmer, had strapped on snowshoes and a backpack loaded with bottles of milk to deliver to families with infants. Nor had he ever told me he had served as a city councilman – that he never mentioned having grown a feeble mustache (barely visible at right) is understandable.

I discovered, as so many others have, that a question asked does not equal a question answered. We may hear great stories, wonderful memories, or angry orders to “leave it alone.” In telling me an unflattering story about his great-grandfather Charles Otis Cony (1848–1928), my father admonished me that I couldn’t “write about it until I’m gone.” Charles had been dead for over fifty years at that time, so I was puzzled at this demand, but I complied: Dad has now been gone for 21 years! I’m good!

I have found unending inspiration for stories in the pile of family memorabilia bins, a hunt I now view as “dumpster diving” (dead vintage hearing aids, well-used toenail clippers, and the odd set of dentures were discarded – quickly). Whatever falls out of walls and ceilings during renovation – photos, audio recordings of my niece’s baby sounds, scrapbooks, and newspaper clippings – becomes fodder for my collection of family stories. Some stories can be verified, some will gain mythical status over several generations, and all will be valuable to our descendants.

Finally, I agree with both Stephen King’s observation, “When it comes to the past, everyone writes fiction,” and Jill Lepore’s “History is what is written and can be found.” Somewhat horror-stricken, I have realized that it is now my turn to decide how I want to be remembered, what events in my life I want recorded, and what, if anything, I want buried, burned, or blessed. I’ll become a story in the view of those I leave behind, so let it be a great story! (Meanwhile, hand me some matches!)

We should never become just a face in an unmarked photo, nothing more than signatures on a page or next to a hashtag. Fiction or fact, memories morphing into family stories are what bind us to our families and our lineages. So mark those photos! Do that research! Tell those stories and write them down! You think no one will be interested in what you have to relate? They will be! After all,

You’re reading this, aren’t you?

Your thoughts and admonitions about writing the stories are spot on. But, it also brings up the thorny question of what do you do with them after you write? Of course, a well-written and documented piece could potentially be published as a genealogical journal article if it was useful research to their audience. The same might be true if published as a book or article and placed in various genealogical libraries, or historical libraries associated with the family’s location. And, perhaps some family members might be interested if the stories are written and distributed to them in various ways. Then there is the internet; a family blog, attached as stories on public genealogy trees, or a website set up for that purpose. Do you or others have additional ideas?

Great Story Plots, on several fronts in this one I loved it! And what about ourselves, food for thought and has me thinking:)

While I never miss a blog, this is One of the few blogs that I actually printed out for further contemplation and perhaps sharing.

I started keeping a journal after 9/11. I don’t write in it every day, mostly special occasions. My sons and grandchildren can read in my handwriting how I felt the day they married and when I learned I was going to be a grandparent as well as all those special days since. I started typing my memories of childhood events. Christmas morning, Easter Sunday’s, birthdays, first bicycle, learning to swim, stories about childhood friends. I try to date them as accurately as possible. If there is a photo, I include it. I’ve included all the stories that we tell when the family is all together. Remember, for the current events include the weather on that day and what kind of car you were driving. Long after I’m gone some one of my ancestors will enjoy seeing a picture of my first car, a 1961 Lincoln Continental. There will be sad stories also, but that’s life. You have a million stories and they are all good, write them down.

Great thoughts, wonderful family stories.

Even those in a family who may not seem overly interested in their lineage, are in fact interested. Don’t let them fool you. And those who are openly curious will be eternally grateful that someone in the family, someone like you, took the time to record history.

Oh dear, the postmodernist mantra that “all history is fiction” has come to NEHGS. Not ALL is fiction: there are the “who, what, where and when” to the best of what is recorded and what we can find…the “why” and the “how” – not so much. It seems to me that much of what we do as family historians is to sift the fact from the fiction. And, yes, sometimes to tell a good story, it may be embellished, but as Hilary Mantel wrote, “when you’re writing historical fiction, if you say there was a full moon that night, there had better have been a full moon.” I fall in that camp.

I agree Elizabeth, good one, keeps us on our toes:)

I used to use a journal to write my thoughts, which were mostly based on my emotional response to whatever was going on at the time. Often it gave me an emotional release, but wasn’t always something I cared to share with others. Most of those were eventually shredded, with the only ones preserved that represented a sort of milestone in my life. However, over the past couple of years, I began to keep a daily gratitude journal and found it a great start of the day.

Now I have grown to see it in a broader sense. An actual record, some of it purely factual. I also record my vital health stats as well my husbands. I am now almost 82 and have serious health issues. This record helps me remember later if some problems show up.

But most importantly, I often now quote something from the newspapers or books I am reading and then take off on that. I even cut out small articles and cartoons and paste them in the journal. I write more objectively about our own lives. I think the future generations will get a picture not only of us, but also of the times.

When I was 7 or so years old, I lived with my grandparents in Wisconsin and wrote to my parents living in Arizona. My mother kept those letters and gave them to me during her last years. They also contained a few letters from grandparents wrote to my parents. She had kept none of my parents’ letters to me or my grandparents. I have transcribed those letters and added commentary as to what was happening in the world (war, of course) at the time. They revealed to me an unknown fact that my grandfather had a serious heart condition; that my grandmother’s name, who we had also called “Anne,” was really “Anna.” These will be passed to my children.