You’ve probably heard the story: “My ancestor’s name was changed at Ellis Island!” But you also probably know that this is a myth; immigration officials at Ellis Island did not randomly alter incoming passengers’ names. However, the surnames and given names of one group of immigrants, French-Canadians, frequently did change when our ancestors crossed the border.

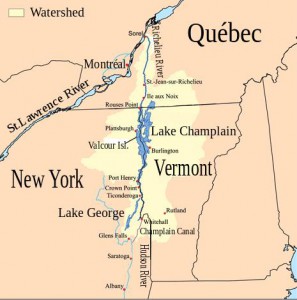

Throughout the centuries, migration from Quebec was driven by poor agricultural conditions, overpopulation, and inadequate employment opportunities. Settlers typically came down the Richelieu Valley into the United States, choosing to try their fortunes in Vermont or northern New York (see Figure 1)[1]. When they began to put down roots and buy land, get married, and baptize children, their names as recorded by clerks and priests morphed into something different. The examples below, from nineteenth-century century Vermont, illustrate what happened.

First, English-speaking clerks or priests wrote the French name phonetically, according to English rules of pronunciation. Most settlers at the time were illiterate and wouldn’t have known if their names had been captured accurately. Thus, the French surname “Bousquet” could become “Bostwick,” Chouquette “Shackett,” and Michaud “Mitchell.”

Second, clerks or clergy could translate the French name into its English equivalent: e.g., Lenoir becomes “Black,” Roi becomes “King.”

Third, confusion about “dit” names could lead English speakers to choose (and Anglicize) one or the other of a Quebecois family names as the American surname. For example, Homand dit Francoeur sometimes became “Francoeur” (my family) and sometimes became “Oman.”

Finally, there is the occasional name change that doesn’t fall into any of the above categories. My personal brick wall was the given name recorded by a Vermont clerk of “Nelson.” What was his name prior to emigration? I couldn’t find a candidate Nelson in any French-Canadian records. Thanks to the Gassette book mentioned below, I learned that “Nelson” was “Narcisse” in Quebec records. Who knew?

Three helpful sources will assist family historians seeking their French-Canadian ancestors. The American-French Genealogical Society has an online list of French-Canadian Surnames and possible variants in the United States.[2] Véronique Gassette has published a spiral-bound book, “French-Canadian Names: Vermont Variants, through the Vermont Genealogical Society. Finally, RootsWeb hosts a list of “dit” names typically associated with a specific family name.[3]

Notes

[1] “Richelieu River,” accessed at Wikepedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richelieu_River 23 March 2016, citing Champlainmap.png: Kmusserderivative work: Pierre_cb – Champlainmap.png, CC BY-SA 2.5.

[2] American-French Genealogical Society, “French-Canadian Surnames: Variants, Dit, Anglicizations, etc.,” accessed 23 March 2016.

[3] http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~unclefred/DitNames.html, accessed 23 March 2016.

Right even my paternal Grandmother who was a Brouillette, used her shortened surname as Bruette on her wedding application in South Dakota. She was French Canadian from a family who had come into Decator, Ill. then made their way to S.D. Territory by the time she was born. I couldn’t find her spelling on anything in S.D. until someone suggested I try the other spelling, then they showed up all over the place:)

I associate “Brouillette” with Vincennes, Indiana. It may have been that your French Canadian ancestors in Decatur, IL had come from, or at least through, Vincennes at one time.

Thank You for this reply, I thought I had lost the email that came with it. As it happened I was researching another ancestor and came across an article so went back to this original source in Vita-brevis to find this so I could answer about what had been found there. “Michel Brouillet, Vincennes Fur Trader, Interpreter and Scout,” by Richard Day, Curator, Old French House, Vincennes. So I do have a very interesting file about the Indiana Brouillet family. Have made no connection for sure with that line, the families were large of course, but in Dubuque, Iowa found a clearer connection to the family line who showed up in South Dakota Territory where my Grandmother was born in 1867, in Vermillion as it was then known as a Postal site.. However her parents are buried in what is now Jefferson, Union Co. SD in St Peters Cemetery where we have paid our Respects and have photos of their Gravesite. So interesting what we come across when doing research. Thank You again for bringing this back to my memory.

Thank you not only for the reference recommendations but for the Narcisse/Nelson hint. I have several ancestors named Narcisse who I keep “losing” and I would never have thought to look for them as Nelson.

And, French spelling also worked in reverse for some families who came to Quebec from the US: Drew became Droux. Certainly easier than the more complex examples mentioned.

The Narcisse-Nelson switch is quite common. There is also Étienne-Stephen, Pierre-Peter, Jacques-James, Honoré-Henry, Magloire-Maguire and Philomène-Phoebe.

Yes, the New England captives brought to New France had their names changed: Farnsworth-Phaneuf, Rising-Raizenne and Drew to Ledru. This also happened to some Germans who settled in Quebec. Kammerer-Camaraire, which became Cameron in Vermont.

I have heard that names did not change at Ellis Island, that the accepted story is a myth. But- I have personal experience that names did change, usually because of language interpretations. So, when that comment is made, I discount what I hear, because I have found five different spellings of my family name, and one of those probably was a shortening. I do not think that it was deliberate, but misunderstandings happened with the best of intentions, and renaming did occur. Thanks for your blog- I enjoy it.

I have always understood the reasons for very early variants for my ancestors’ names due to (often before the 17thC in for example, the UK), many persons being unable to read and write, therefore, many names were “entered” into records phonetically by ministers etc. Often this led to many versions or variants of both forenames as well as surnames….However, what I have not been able to understand is those people who changed the spelling of their names when they left England circa mid 17thC when they arrived in America. For example, my “American” name is Tillinghast…but immediately prior to my ancestor arriving in America the archived records of England show the spelling fairly consistently as Tillinghurst or Tellinghurst. Thus the ending from hurst to hast. I have noticed the same with other persons arriving from the UK in that period. Anyone have any suggestions as to why this might have happened?

This might be a situation where the “r” got dropped because of a New England or Southern accent, but the “r” might be found later. My mom used to say that she drove a Toyoter cah. My Hezekiah was recorded as Hessie Carr.

My mother exactly!

Tillinghast – I just looked up the word origin for HURST – “Old English hyrst, of Germanic origin; related to German Horst .” Meaning, a sand bank, or hillock. Perhaps useful or not. But, phonetic spelling is likely the culprit, especially considering probable variations with accents.

Hurst also refers to “woods” and in a few early sources that is the usage in this instance….The family is of Titla, early “ruler” of the southeastern area of England…thus of Titla’s woods…Ti or Tytlia’s Hurst….and so forth as it changed over the centuries.

I would accept the phonetic explanation if this particular ancestor weren’t well educated and was able to write and read….thus would have spelled his own name for someone or written it himself.

But thank you for your suggestion…appreciated.

At Ellis Island names were entered as understood by the people hearing names as spoken to them. PLUS not everyone understand sounds in the same way.

Add in that someone who did not understand English might understand a question far from what the asker intended to convey.

Also, some immigrants decided what name to use before leaving a ship as a result of discussions with neighboring passengers as my father-‘s great uncle did. He and his neighbor each chose English sounding names which had nothing to do with their birth names.

German immigrants also sometimes Anglicized their surnames so that Zimmerman became Carpenter and Schwartz became Black. This happened especially during and after WWI. But, as you say, the change was made by immigrants themselves, usually after a few years in the community and not at Ellis Island.

All those same things happened in early California records as well. First, Spanish did not have standard spelling until the mid-19th century, so that “b” and “v” were uses interchangeably, as were “s” and “z,” “i” and “y,” etc. Earlier records spelled the very common male name “Josef” but later “José” (generally not a problem for most search engines but the online Early California Population database with all the California missions records is entirely specific by character). As English-speakers became a larger part of the population, there were translations of names, e.g. “Blanco” into “White,” and any number of given names into their English equivalents. Plus names were spelled as they sounded to English speakers: my favorite (I still laugh when I see it) is the Juarez family enumerated as “Wharis”! Another tricky thing is that most Spanish women kept their own family surnames, but census takers often didn’t know this, so it can be tricky to track women back and forth between their maiden and married surnames. And as this article mentioned about the French Canadians, most of the early Californians were not literate and so were not able to instruct or correct priests and officials when listing their names. My great-great-grandmother’s family had their name spelled Lisalde, Lisald, Elizalde, Elizalda, Elesalda, Allisalda…to name just a few few variations!

Huge help. My mother’s family is French Canadian. Hard to find sites geared to us that are not modern day with a British spin on history. However, i am somewhat new to this and I may just not have found the right path to the sources I need. Many thanks.

I did the research to try to find my Grandmother’s family in South Dakota Territory (now SD) it was explained to me the LL’s would be silent in French so her Brouillette surname became Bruette without them in pronounciation. The man who suggested the site to me was so long ago, I would need to get out my files to see if I kept what internet site he suggested. These sites have changed too, but I think any French Canadian site in Canada would still have suggestions as to spelling changes to sound more English.

The ‘ll’ is not silent; it sounds like a y. Sounds something like Brewyette.

It was spelled by My French Canadian Grandmother herself as Bruette, making them silent. Her parents used the spelling Brouillette and some still do pronouncing the LLs. Perhaps there were others using your spelling, have not come across them in SD or IA.

No, the double L is not silent; it is pronounced as a Y. Bruyette would be closer to the French sound than Bruette, which could sound like “brouette”, a wheel-barrow.

In my research the French-Quebec name “Brasseau” was “translated by ear” to “Brazo/Brozzo” and about 13 other similar variations! And, my Beauchamp” relatives became “Boshaw’s” … just one of the challenges of finding them!

Have heard Beauchamp pronounced Beecham too:)

I was told by my mother (not alot of detail) that my ancestors were named Beauchamp before becoming Boshaw (as my last name is Boshaw). I would love to know more. How would I go about finding it out without costing me an arm and a leg?

Interesting your Beauchamp became Boshaw, have seen this pronounced exactly as seen as in “Bow-Champ,” but in some places “Beech-ham.” In parts of South Dakota my Grandmother’s maiden name Brouillette, is pronounced using the two Ls. But she was finally on her Marriage certificate without them to Bruette. But have seen Brown dit Brouillette, some have just become Brown leaving out the dit surname.

My Secor maternal side is seen so many ways Seycar, Secoure, Secaur, Secore., it is French, but not in my line French Canadian.

I love this about surnames:)

There are Brouillettes who became McLean.

Grandma married a McGraw, for her first marriage, I cannot find him. Somehow he disappeared out of her life and she subsequently married my Grandfather and helped raise her son who was a McGraw all his life. I found him deceased in Great Falls, MT.

My French Canadian ancestor, Mathias Allard, was known for a long time (and had his kids baptized with the surname) as John Gould, which wrecked havoc with their locations until I did a directory search, knowing they lived on Charter street in Salem, and finding all their first names correct in the corresponding 1880 census. The question is, why Gould and its relation to the name Allard, and why did the entire family eventually revert to the name Allard again?

Interesting, Gould is often found for the French-Canadian names Doiron and Doré. I have not seen it for Allard, which doesn’t usually change much except to become Allore.

The French word for gold is l’or, which sounds like the second syllable of Allard. It’s an innovative translation, much the way Frappier became Strikefoot or Lesieur became Sawyer.

Great post! We had an instance in our tree where luckily the priest had written in their old name – Loranger – next to their new name – Wright, in the baptismal records. Even better – they later changed it back to claim a Canadian inheritance!

Thank You for your wonderful post! You may have helped me break through a brick wall!

My “RICH” ancestors appear in Vermont around 1790, and then moved to Crown Point by 1810. For 25 years, I have searched for the German form REICH, and have been in contact with the RICH Family association, with no success in finding these ancestors prior to 1790.

Is it possible that my ancestors were originally Richelieus or Richards, etc, and then shortened their surnames to RICH? (My family’s oral tradition is that Felix RICH fought with Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, and then later fought in the War of 1812 from Crown Point.)

Houde dit Desruisseaux became ‘Brooks’ after immigration from Quebec to Connecticut. Translation of Des ruisseaux is ‘by the brooks’. It took a few years to make the connection.

So interesting, I replied about the Brouillette surname changing to Bruette, and on the marriage certificate it is spelled that change. She married my Grandfather Brooks. Must look into this although have found a Canadian connection to him, never thought about his surname ever being anything else. His Mother’s maiden name “Bump” and her Mother maiden name “Upper,” all from Canada.

Someone commented about finding Brouillette in Indiana, yes, have run across that, but have lost the email that sent the comment.

Name changes at Ellis Island continued into the 20th century. My father emigrated from Sweden in 1923 and his name made a simple change at Ellis Island — from Jonsson to Johnson. I never thought to ask how he felt about that. I had a difficult time when I first tried to find him in Ellis Island records, not knowing which spelling would be there, PLUS, he was called by his middle name, signed with the first Initial and middle name, or sometimes just his two first initials. So I had to look at O. Fabian Johnson, Olof Fabian Jonsson, O.F. Johnson, and every other variation. I found him when I looked for the name of his brother who immigrated with him — and HIS name had had the first and middle names joined as one!

Very good timing! You confirmed what I just discovered. My husband always thought his ancestors all came from England. He was a little surprised when I showed him that his great grandfather Frank Mitchell was the great grandson of Germain Michaud of Quebec, Canada.

My first visit to the blog, and what an interesting topic. My great grandparents, Pierre Poulin and Marie Perpetue Cloutier migrated to Brewer, Maine, and voila, they became Peter Pooler and Eliza Cluckey Pooler. Peter’s uncle, Jean Poulin, had preceded him in Maine, and was already John Pooler. But Cluckey? Like a chicken? I think John must have been the one to say, “Lose the French, kids.” Just a thought.

This is in part due to a dialectal pronunciation of Cloutier. Some dialects of French pronounced the T sound as a K. This is evidenced in a number of transformed French-Canadian surnames: Cloutier-Cluckey, Trottier-Truckey, Gauthier-Gokey, Pelletier-Pelkey, Éthier-Hickey, and Berthiaume-Barcome/Barcomb. Incidentally, Cloutier was also translated as Nailor.

Thank you. Nailor would have mystified me even more.

My paternal grandmother’s maiden name was “RIVES”, with a long i. When I started researching in North Carolina, where she was born, the locals pronounced it “REEVES”. The spelling varied, but the Rives who emigrated from England, began in France, where it translates to RIVER.

Name changes occurred not just among French Canadians migrating to the US, but also within Canada. On the west coast of Newfoundland (the northern part is known as the French Shore, because France had fishing and coastal rights there until 1904) common family names include White (originally Leblanc), Bennett (originally Benoit), Gill/Gilley (originally Galliot). In the Bay St George/Port-au-Port region, which still has some French-speaking communities, there are is an O’Quinn clan (formerly Aucoin) who were given “Irish” names by Irish priests.

Some of my acquaintances say that their ancestors’ names were not changed at Ellis Island, but actually created, that is, they came from Russian, Middle European or Yiddish background with different alphabets. The resulting name was the best approximation in English.

Bousquet became Booska or Buskey. Francoeur often became Hart, Shackett is a variation of Choquette, not Chouquette.