This is a big year for honoring Fred McFeely Rogers, who – if not a family member – was a virtual neighbor to millions of us. The United States Postal Service is issuing a stamp in his memory this week, and I was touched to discover that an “icon” honors him near the pew he habitually occupied in a church my great-great-great-great-grandparents inadvertently helped found in 1838.

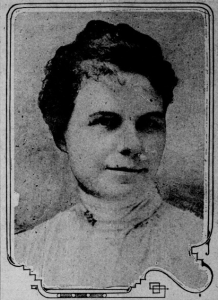

However, this story is about a very different Mr. Rogers, the first husband of the second wife of my great-grandmother’s sister’s first husband. Got that? I’ll rewind and explain: my great-grandmother’s sister, Kate Bottomes, married a man named William H. Rardon in 1891. By the 1900 census, Kate was divorced from Mr. Rardon; he married Lillian Vestalina (Roberts) Rogers in 1908. In August 1912, Lillian Rardon got some very interesting news: her first husband, James Wood Rogers, had been killed by government soldiers in Belgian Congo, on 8 October 1911.

It wasn’t until 2 January 1912 that the State Department in Washington, D.C. received the news via Cairo, and another seven and a half months elapsed before the news reached Lillian. It rated front-page news in California newspapers, and a unanimous resolution in the Congressional House directing the State Department to investigate. However, even Hollywood could not have come up with a more bizarre plot.

A native of Michigan, Mr. Rogers moved to California in the 1880s and became a produce dealer. He acquired the rights to the Wedge Mine near Randsburg, California, in November 1896, and after taking $130,000 of ore out in seven months, he sold his rights and moved to the Klondike. There he invested in more mines, but tragedy seemed to have struck when the Los Angeles Herald reported on 17 June 1900 that he had been shot, probably fatally. This proved to be only the first time his wife believed him dead!

[Even] Hollywood could not have come up with a more bizarre plot.

On 13 February 1904, the Los Angeles Herald ran a salacious article under the following multiple headlines: “Missing Man Much Wanted,” “J.W. Rogers of Corona Disappears,” “Made Money in Klondike But Unsuccessful Here,” “Drew Nine Hundred Dollars From Bank and Bought a Suit of Clothes Two Weeks Ago, and Has Not Been Seen Since.”

The article described three theories: his wife suspected foul play and feared him dead, his bankers believed that he’d skipped out leaving $20,000 in debts, and his former partners believed that he’d gone back to the mines in the Klondike. Guess who was right?

On 22 March 1904, James Wood Rogers applied for an emergency passport in Cape Town, South Africa, for himself and his wife, Lillian V. However, this is the only evidence to suggest that she actually made the trip with him, and it seems doubtful that she did based on subsequent events. According to the San Francisco Call of 21 August 1912, Rogers could have been the model for Kurtz in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness … if it hadn’t already been published a few years previously.

“The authorities declare that Rogers had a domain over which he exercised all the authority of a despot. He was an elephant poacher and a trader in ivory in express violation of the laws governing this traffic. Complaints of his activities had come so persistently to the ears of the authorities that it was decided to capture Rogers dead or alive.” The article then went on to describe how Captain C.V. Fox and six soldiers spent three weeks tracking him through the jungle. “Rogers was cornered in a hut in a mountain fastness … suffering from a mortal wound inflicted by Fox’s men in the last hours of the hunt. He was surrounded by a retinue of natives and one white man.”

The article finished by stating that Mrs. Rardon would be bringing Rogers’s remains to Michigan for burial in his family’s plot, and that she was his sole heir, having married her second husband under the belief that Mr. Rogers had died. There was just one little problem with this claim.

The Los Angeles Times ran a notice 1 February 1905 that Lillian V. Rogers had filed for divorce from her husband, James W. Rogers, and the Oakland Herald reported on 29 August 1906 that an interlocutory decree had been issued the previous day in this case. Oops! I guess Lillian had forgotten all about that in her excitement.

Wonderful story! I’m working on an embezzler who escaped NYC and ended up in a Fraser River mining camp around the same time. Great place to hide out under an assumed name and hide the money by investing in the operation.

Fellow researchers, if you haven’t yet found this level of scandal, keep working on the FAN (Friends, Associates and Neighbors) network and you will be rewarded.

I love your second paragraph! Of course one of the difficulties in tracking down infamous relatives and associates is—as you pointed out—the fact that they may have changed their names. Good luck with your sleuthing.