Americans tend to reject the notion of operating within a “social class” structure, although it is sometimes easier to see ourselves as “better than” one person as opposed to “lesser than” another. At the same time, we consume (and relish) the higher gossip associated with European royal families and Hollywood movie stars, and Cleveland Amory – one among a number of authors on the subject – devoted a whole book to the question “Who Killed Society?”[1]

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Americans treated “Society” as a kind of blood sport. In New York, for instance, a lady (sometimes a gentleman, or a married couple) “ran” things for much of the period; the benevolent dictators included Mrs. James I. Jones,[2] Mr. and Mrs. August Belmont,[3] Ward McAllister,[4] Mrs. William Astor,[5] and – at the turn of the century – a triumvirate (Mrs. O. H. P. Belmont,[6] Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish,[7] and Mrs. Hermann Oelrichs[8]). Among the structures they created to demonstrate their powers (and good taste) were groups like the Patriarchs[9] and the Family Circle Dancing Classes (F.C.D.C.), while the most famous creation of the period was McAllister’s “400,” that select group of men and women in Society who counted, and who fit comfortably in the ballroom at the Astors’ house on Fifth Avenue.

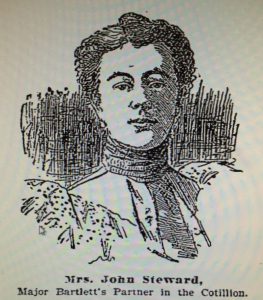

I was recently looking through The New York Times database when I stumbled upon a familiar name: Mrs. John Steward, Jr. I grew up looking at her portrait, painted by Léon François Comerre: she was my grandfather’s aunt, born Cordelia Schermerhorn Jones (1849–1920). The first reference I came to in the Times database was for the Patriarchs’ Ball of 10–11 December 1894, and to my surprise the article included an illustration of Mrs. Steward and the information that, with Major Franklin Bartlett, she had led the cotillion that opened the ball (at 1:30 a.m.).

In the Times’ coverage of the Patriarchs’ and F.C.D.C. balls, there is always a reference to the couples who led off the dancing – this is an easy way to keep track of who was on the rise. (It’s less easy to see who was in eclipse; often people coped by going abroad to economize.) A little sleuthing led to an earlier period of Steward ascendancy during the hectic pre-Lenten season of 1881, when Mrs. John Steward, Jr., led the cotillion with three different partners at both of the Patriarchs’ balls as well as one of the F.C.D.C.

But why? Two or three reasons suggest themselves. As her maiden name indicates, Cordelia Steward was both a Jones and a Schermerhorn, counting Edith Jones (later Wharton) among her cousins. More to the point, her mother was Mrs. James I. Jones, and Cordelia’s aunts included Mrs. William Astor, who, by the end of the 1880s had achieved her own special status as, simply, Mrs. Astor.

As the Comerre portrait confirms, Cordelia was lovely; she was also rich enough that her husband (my great-great-uncle John Steward [Jr.][10]) did not have to work, even after his father was ruined in the Crash of 1873. It is worth noting that the John Stewards lived abroad for much of their marriage, although not, presumably, for economy’s sake. This, in turn, might help explain why Cordelia shone so brightly in 1881 and then again in 1894 – but only in those years.

1881

18 January: “The cotillion was begun at 1 a.m., Mr. Frank Sturgis and Mrs. John Steward, Jr., leading, Mr. Ward McAllister and Mrs. W. W. Astor[11] on their right, and Col. Delancey Kane[12] and Mrs. F. S. G. d’Hauteville[13] on their left. The favors were flowers and imported articles of vertu.”[14]

1 February: “A feature of the menu was the abandonment of salmon and the introduction of truffled turkey, a Parisian luxury. At 12:30 o’clock the cotillion was begun, led by Mr. C. R. Hone,[15] who danced with Mrs. S. S. Howland.[16] On their right were Mr. Ward McAllister and Mrs. J. Lawrence Lee,[17] and on their left, Mr. Delancey Kane and Mrs. John Steward, Jr.”[18]

15 February: “The cotillion began at 1:30 o’clock. It was led by Mr. Charles Russell Hone, dancing with Mrs. J. B. Potter.[19] On their right were Col. Delancey Kane and Mrs. George Peabody Wetmore,[20] and on their left Mr. Ward McAllister and Mrs. John Steward, Jr.”[21]

10–11 December 1894

“The ball began unusually late, owing to the opera and one or two large dinners which preceded it. It was supposed to begin at 11:30 o’clock, but few guests arrived before midnight… After supper, at 1:30 o’clock this morning, Lander’s orchestra began playing in the main ballroom, and the cotillion commenced. It was led by Franklin Bartlett[22] and Mrs. John Steward… Carriages were ordered for 3 a.m., but it was some time after that when Delmonico’s doors closed behind the last lingering guest.”[23]

“Few costumes were more striking than that of Mrs. John Steward, who led the german [i.e., waltz]. Mrs. Steward wore a Paris gown of lilac-ribbed silk, with wild roses trimming the bodice, and rich lace on the skirt.”[24]

Some of the people I have named remain famous to this day: Mrs. Astor, the Belmonts (and their daughter-in-law), and Ward McAllister. They are famous for conspicuous excess, perhaps, and for playing at Society as it was played at the European courts of the period – if without the superstructure of inherited status that Americans tend to spurn. Mrs. John Steward, Jr., is not remembered in this group, nor should she be, but for a season or two she twinkled as bright as any star in the Knickerbocker firmament.

Notes

[1] Who Killed Society? (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960). Cordelia Steward’s nephew Augustus Van Horne Stuyvesant, Jr. (1870–1953) is featured in the last chapter of the book.

[2] Elizabeth Schermerhorn (1817–1874) was married to James I. Jones 1839–58. Using Mrs. Jones as an example, Lloyd R. Morris notes that “Feminine social leadership was in perpetual dispute” (Incredible New York: High Life and Low Life from 1850 to 1950 [New York: Random House, 1951], 25).

[3] August Belmont (1813–1890), initially the Rothschild family’s representative in New York, married Caroline Slidell Perry in 1849.

[4] Ward McAllister (1827–1895), notable for the ferocity with which he directed his friends’ leisure activities.

[5] Caroline Webster Schermerhorn (1830–1908) was married to William Backhouse Astor, Jr. 1853–92; she gradually pared away his name’s distinguishing features until she became Mrs. Astor. Her daughter Emily married John Steward, Jr.’s first cousin James John Van Alen in 1875.

[6] Alva Erskine Smith (1853–1933), the suffragist and architectural patron, was married to William Kissam Vanderbilt 1875–95 and to the Belmonts’ son Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont 1896–1908.

[7] Marian Graves Anthon (1853–1915), famed for her breezy speech, married railroad president Stuyvesant Fish in 1876.

[8] Theresa Alice Fair (1871–1926), a silver heiress, was married to Hermann Oelrichs 1890–1906; her sister Virginia was married to Alva Belmont’s son William Kissam Vanderbilt, Jr. 1899–1927.

[9] The Times, almost certainly quoting Ward McAllister, described the Patriarchs as the American Almack’s, “one of the most brilliant collections of people London had ever seen… In no sense are the ‘Patriarchs’ assemblies, for in this City an assembly would embrace at least from 1,000 to 1,800 people. They are simply private balls, given by 48 gentlemen, and at Delmonico’s [restaurant], instead of at their own houses, as they find their own houses too small comfortably to contain the fashionable world” (“Second Ball of the Patriarchs,” 18 January 1881). The remainder of the 1880s would be devoted to building houses large enough to hold balls on the scale the article contemplates.

[10] John Steward (Jr.) (1847–1923) was married to Cordelia Schermerhorn Jones 1871–1920.

[11] Mary Dalhgren Paul (1858–1894) married Mrs. Astor’s nephew William Waldorf Astor (1848–1919) – later the 1st Viscount Astor – in 1878.

[12] Colonel De Lancey Astor Kane (1844–1915).

[13] Susan Watts Macomb (1849–1928) married Frederic Sears Grand d’Hauteville in 1872.

[14] “Second Ball of the Patriarchs,” 18 January 1881.

[15] Charles Russell Hone (1849–1920).

[16] Frederika Belmont (1854–1902), a daughter of the August Belmonts, married Samuel Shaw Howland in 1877.

[17] Margaret Lewis Livingston (1843–1919) married John Lawrence Lee in 1868.

[18] “A Largely Attended Ball,” 1 February 1881.

[19] Mary Cora Urquhart (1857–1936) was married to James Brown Potter 1877–1900; she later went on stage under her married name.

[20] Edith Malvina Keteltas (1848–1927) married George Peabody Wetmore in 1869; he served as Governor of Rhode Island 1885–87 and as a U.S. Senator from Rhode Island 1895–1907.

[21] “Two Successful Balls,” 15 February 1881.

[22] Franklin Bartlett (1849–1909), later a congressman from New York.

[23] “The Patriarchs’ Dance,” 11 December 1894.

[24] “Gowns and Matrons and Maids,” 11 December 1894.

Society is still there just not on the “Society” page of the newspapers. It is alot more subtle until you encounter it.

I am reminded of the quote, “It’s still magic even if you know how it’s done…” – What a beautiful time indeed. Absolutely stunning!

Scott,

I loved reading about what Cordelia Schermerhorn Jones’ “Society” was like, partly because I’m related to her. She must be descended from Jacob Janse Schermerhorn, who arrived in New Amsterdam (New York City) in 1638 from Holland as a teenaged apprentice. In the early years, immigrants intermarried with other Dutch families because the colony was so sparsely settled. Thus he’s related to most other New Amsterdam families. The same thing happened, of course, in New England out of the same necessity. “City of Dreams: The 400-Year Epic History of Immigrant New York,” by Tyler Anbinder is a wonderful 2016 book covering this history. I haven’t figured out yet exactly how Cordelia Schermerhorn Jones fits into my Schermerhorn line, but everything I’ve read about the Schermerhorn family is quite clear that they’re all related, one way or another. Jacob Janse became a prominent man in his day, though “Society” wasn’t quite what it was in his descendant Cordelia Schermerhorn Jones’ time.

Thanks for your post,

Doris

I almost always enjoy these posts so am sorry to say that I find this Gilded Age excess utterly revolting–for many reasons surely familiar to anyone knowledgeable about American history. Both history and morality condemn their way of life.