My recent post about twins in the family – correcting my ancestor Sarah (Johnson) Eaton’s ancestry – reminded me of various corrections to my family papers over the years. As I had indicated there, when I started my genealogical research, I was given an enormous head start on my native Connecticut ancestry. Two friends of my great-grandparents had prepared family charts tracing nearly all of my grandfather’s ancestors back to the immigrants in the 1600s. While this was a terrific help, over the years I have found sometimes that this material wasn’t always right. Many times the ancestors on the charts were listed in published genealogies, but my attempts to confirm the line have led me to revisit these ancestors, sometimes turning them into “former ancestors.”

I’ll share some of the more interesting examples I’ve discovered over the years, and some that have happened very recently, often when working on research projects for other people. My research on these families is not for naught though, as I will frequently recognize some of my former ancestry in members’ charts when doing consultations, so I’ll still remember the sources I had used to correctly research these families.

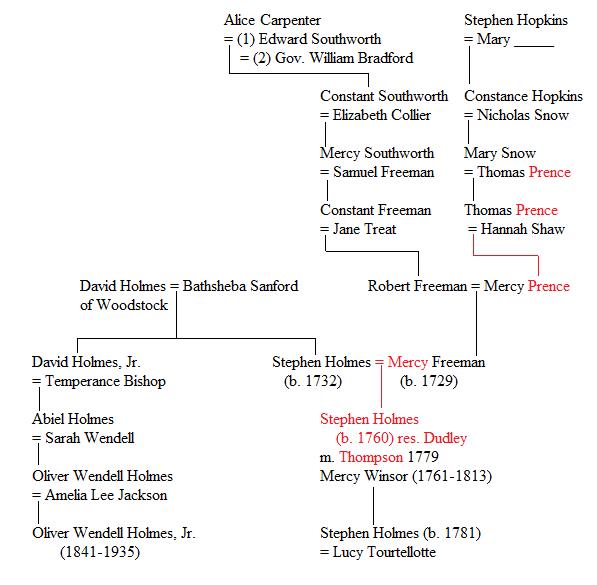

My great-grandmother’s great-grandfather, Stephen Holmes (1781–1859) of Thompson, Connecticut, was identified on the above chart as the son of “Stephen Holmes” and Mercy Winsor. The ancestors of this “Stephen Holmes” of “Dudley” was carried forward on chart 14, identifying him as the son of Stephen Holmes and Mercy Freeman. This elder Stephen Holmes was the son of David and Bathsheba (Sanford) Holmes of Woodstock (great-great-grandparents of Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., whose grandfather was a Woodstock native). Mercy Freeman (born in 1729) was identified as the daughter of Robert and Mary (Prence) Freeman, and granddaughter of Constant and Jane (Treat) Freeman and Thomas and Hannah (Shaw) Prence, all of Cape Cod.

While the charts we had did not attempt to go further back, this was in the beginning of my genealogical research with my aunt in the early 1990s, and we researched these families going back to early Plymouth with a descent from Governor William Bradford’s step-son Constant Southworth and Mayflower passenger Stephen Hopkins. This got us excited and interested in joining the Mayflower Society.

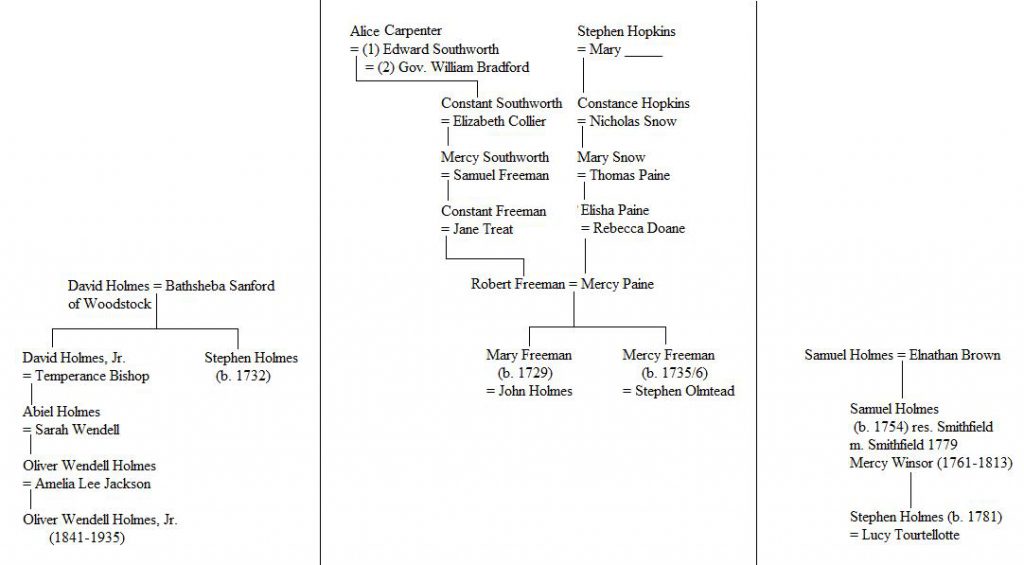

However our bubble was quickly burst as we identified several incorrect items on the above chart. Firstly the surname “Prence” should really be Paine. Robert Freeman had married Mary Paine, daughter of Elisha and Rebecca (Doane) Paine, and granddaughter of Thomas and Mary (Snow) Paine.[1] These corrections still had us descended from Mary Snow, the granddaughter of Stephen Hopkins, but not for long.

While Robert and Mary (Paine) Freeman did move from Cape Cod to northeastern Connecticut, their daughter Mercy Freeman (born in 1735/36) married Stephen Olmstead, while their daughter Mary Freeman (born in 1729) married John Holmes (who moved from northeastern Connecticut to Dutchess County, New York, and did not have a son named Stephen).[2] The earlier mentioned Stephen Holmes, son of David and Bathsheba, did exist, but did not marry anyone named Freeman.[3]

Also, our “Stephen Holmes,” husband of Mercy Winsor, was actually named Samuel Holmes (who never lived in Dudley, rather mainly in Smithfield, Rhode Island), and turned out to have been born in Scituate, Rhode Island, in 1754, son of Samuel and Elnathan (Brown) Holmes, with no connection to this Woodstock Holmes family behind the Supreme Court justice. (This senior Samuel Holmes of Scituate is still a brick-wall, while his wife descends from early Rhode Island families, none of them in Cape Cod.)[4] It would be another fifteen years before I found a “true” Mayflower ancestor, but as a result I learned a great deal about these early Holmes and Freeman families improperly melded together on an old ancestor chart.

Notes

[1] John D. Austin, Mayflower Families Through Five Generations Volume Six – Stephen Hopkins (Plymouth, Mass.: General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 2001), 1-8, 13-14, 40-41, 175. Obviously we used the earlier edition (published in 1992) in the 1990s. The basic summaries of these families discussed has not changed between the editions.

[2] Ibid., 176. I really didn’t get that far at this point: I just turned the page! For John Holmes, also see Robert S. Wakefield and Margaret Harris Stover, Mayflower Families Through Five Generations Volume Seventeen – Isaac Allerton (Plymouth: General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1998), 147. This John Holmes also had Mayflower descents from Isaac Allerton, Stephen Hopkins, and Francis Cooke. Oh, well!

[3] Clarence Winthrop Bowen, Donald Lines Jacobus, and William Herbert Wood, The History of Woodstock, Connecticut – Genealogies of Woodstock Families, 7 (1943): 91. This Stephen Holmes (1732–1773) left Woodstock, married Anna Paterson, graduated from Yale College, and settled in Saybrook, Connecticut.

[4] James Newell Arnold, Vital Record of Rhode Island …, 3 (Providence County, Scituate): 43.

James Pierce Root, nineteenth century genealogist, reminds us that one of the idiosyncrasies of genealogy and family research is that one is never able to bring it to a close. That the researcher can rarely if ever be sure of having accessed that “last storehouse of records” confirming the details of his or her family history. He further reminds us that “…no one should wait for absolute perfection before committing his work to the press.” There is a temptation to withhold from publishing, and continue trolling archived records for those bits of missing information that may in the end no longer exist due to destruction or deterioration. Authors may also be tempted to continue to edit and revise their works in pursuit of faultlessness. However, refraining from publication must be avoided. There are a great many benefits that can be achieved by releasing the body of facts found to date, even if what is published is subject to corrections. This commentary is a very good example of how the publication provided the opportunity to clarify and correct previously thought “correctness”.

In your final chart, you misspell the name Olmstead as Olmtead.

Loved the title of your post, “Former Ancestors.” Yes indeed, if one searches the family tree long enough, there are certain twigs that indeed fall to the ground when their attachment to the main branches proves too frail to withstand the “winds of time!” Thank you for a chuckle this morning.

I have been researching since 1977 and I have to admit that I have a large file of Once and Future Ancestors.

“Former Ancestors” is perhaps too ambiguous. How about “Falsely Claimed Ancestors” or “Faux/Supposed Ancestors”? My charts have such as well, and the other day I was notified by the DNA people of another old New England line they connected with mine, which I will now try to check out. It’s a line in which I don’t recognize any names! How much trust will we be able to put into DNA based genealogy?

I learned early on that I needed to be ruthless with the delete button! One bad marriage record and then pages of pedigree are wiped out. Most of mine have been adjustments due to better and more detailed 20th century research (including my own) that allowed more modern genealogists to see patterns that weren’t as clear in the past.

One was a Mayflower connection I had to eliminate: I descend from Experience Mitchell (~1603-~1689) of Plymouth, whose first wife was Jane Cooke, daughter of Hester Mayhew and Francis Cooke (Francis, of the Mayflower). The Cooke connection was believed to be solid at the time that specific family history was published in 1915. Later in the 20th century, it was determined that Experience had three wives, Jane Cooke being the first. My line descends from the second or third wife, neither of whose names are known (or at least they weren’t when I last looked into the matter). By reading one archived Register article in passing I learned of the newly-identified subsequent wives and I promptly wiped out that section of my pedigree! (And eliminated the history attached to my grandmother’s sister’s name, Hester!)

My second really big change was also incorrectly identified in another family history, written by my great-great-grandfather in 1925, His grandfather had spoken to him personally of HIS grandfather, Noah Woodruff. At the time, only one Noah Woodruff was known to have existed, then and there. But there were two, born within a year of each other, one town removed, both married to a “Mary” and both died in the same year. Our history was published as attached to the incorrect Noah’s lineage. I am now working on a correction, which brings us back to the same immigrant ancestor, Matthew Woodruff of Farmington, CT, but which also adds a generation into our Woodruff line! Eliminating that Noah eliminated a lot of “history” – including a connection to some notable Colonials, including Matthew Marvin and John Astwood. I look forward to filling in the blanks with new notables!

It’s all history, and as such must be treated with all the objective tone we can muster. This includes being fully prepared to click “delete” when necessary. It also includes documenting the events of each person objectively, even when it includes unsavory or unpleasant events (hello to another ancestor, William Potter!), which may be a good topic for a future entry, if it hasn’t already been addressed.

Keep up the great work!

People often tell me they pursue genealogy to find “the truth,” but I warn that often we can only *approach* the truth given the materials at hand (even the Genealogical Proof Standard recognizes this). Understanding the limits of the historical and vital records we use helps us to recognize why errors exist and why correcting them–while sometimes painful–helps us all in the end.

It almost looks like the people who wrote the original family history picked a Mayflower immigrant, then “found” a way to connect to that immigrant. I know some people who work backward like that, frustrated for years because they have trouble proving their connection to that famous person.

Lots of us need to learn about designating multiple generations of our constructed ancestral line as “former ancestors.”

NEHGS has done extensive research for me to identify the parentage of my direct ancestor “Lucy Perkins” allegedly born 1728-1739 in Massachusetts and who married Isaac Solomon Andrews of Ipswich, at Ipswich, shortly after 10 Aug 1754. I believe the first 6 of their children were born at Concord and the last 5 at Hillsborough, NH. Many, many amateur researchers (like me) have claimed to know that “their” Lucy Perkins, Mrs Isaac Solomon Andrews was a daughter of Jacob Perkins and Susanna Cogswell. NEHGS says otherwise; that they cannot find Lucy’s parents, so I am content not to repeat the unsubstantiated allegations.

It would be so satisfying to tie up this loose end. … I’m beginning to think Lucy could have been an illegitimate child of a Perkins woman. Lucy Perkins a bastard child still doesn’t appear in the Vital Records of Massachusetts towns, nor in any extant Will probated in Massachusetts. Any suggestions re how to confirm or disprove the illegitimacy theory? Where to look next? I need to find those “future” ancestors.

Thanks!

My grandmother did a lot of research, but didn’t realized that her great grandfather had legal problems with Indiana not recognizing a Kentucky divorce, so he got another divorce in Indiana after several children were born to this second wife and their second marriage in Indiana.

Of course this resulted in her matching children up with the wrong mothers. She did a lot of research on the wrong mother’s family. I’m glad I kept the “unrelated” people in my database, because I eventually found that another branch of the family was related by marriage to them.