The rustic handmade sign above the door said “Ye ol’ Genealogical Research Center Library and Museum.” The letters were in Old English style. They were painted yellow over a green background, and they perfectly captured the upbeat, cheery nature of my friend Tom.

The rustic handmade sign above the door said “Ye ol’ Genealogical Research Center Library and Museum.” The letters were in Old English style. They were painted yellow over a green background, and they perfectly captured the upbeat, cheery nature of my friend Tom.

“Step in,” he urged me. I walked through the door and into his study. This was where he had spent the first fifteen years of his retirement researching his family’s history. Even before I entered the room, I knew what I would see, and I didn’t like it.

Before that, my wife Cindy and I had spent the afternoon with Tom and his wife, Betty, having lunch and reminiscing. I have known Tom and Betty practically my whole life. I grew up with their three children. They are a great, close-knit family. I also knew Tom’s mother, Sybil. (I am not using any real names in this blog, by the way). She was a proud, petite woman who always dressed meticulously and maintained a constant attitude of proper decorum.

Over lunch, Tom described his life growing up. He was an only child, and after his father died suddenly when Tom was very young, he and his mother moved in with her parents and the three adults lovingly doted over the boy as he grew. Betty told me that when she started dating Tom, she fell in love with his whole family. They all had a special bond, she said, and she very much wanted to be a part of that.

When Tom retired in the early 90s, long after his mother and grandparents had passed away, he began to research his family’s history. He and Betty traveled all over the country visiting the places where his ancestors had lived. He interviewed cousin after cousin and collected anecdotes that he added to the records he kept in dozens of notebooks in his Ye ol’ Genealogical Research Center Library and Museum. He self-published a family history book that ran more than 300 pages of single-spaced copy and photographs, and he gave it to his relatives for Christmas.

After much prodding, one of those cousins finally came clean with the shocking truth…

Then one day, when Tom was in his late 70s, he took a DNA test and everything changed. Oddly, he didn’t match any of his cousins who also took tests. After much prodding, one of those cousins finally came clean with the shocking truth: Tom was adopted. When Sybil brought the infant Tom home from the adoption agency many years ago, she made the whole family promise that they would never reveal the secret to him. She said she didn’t want him to feel different.

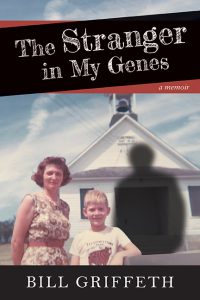

I didn’t know any of this until after I published my book, The Stranger in My Genes, about the DNA test I took that revealed another shocking truth, that my father wasn’t my father. When the book was released in September, almost immediately I heard from friends who told me about our mutual friend Tom’s similar experience. So Tom and I reached out to each other, and not long after Cindy and I drove to their home and took Tom and Betty to lunch. Both are now in their early 80s, but they look and act twenty years younger.

Tom told us how he reached out to his biological family. “I think we might be related,” he told his half-brother when he called him out of the blue one afternoon. Tom learned about his biological parents, who were both long gone, and he developed a relationship with a few of his blood relations. They sent him family photos and told him about his family’s history.

I noticed the distant look in Tom’s eyes as he told this part of the story. He had taken the DNA test four years ago, and while the initial shock had worn off, it was clear that the disappointment had not. And it probably never will.

The walls were lined with several bookcases. And they were all empty.

After lunch, Tom directed us to his study. We stepped through the door, but I already knew what we would see. Tom and Betty had warned us. The walls were lined with several bookcases. And they were all empty. At one time, they had been stuffed with boxes and notebooks full of Tom’s research. But now it was all gone, all of it donated it to a local library.

Tom and I went through the same series of emotions after we learned our new truths. There was denial, then depression, then anger, and finally acceptance. I am at peace with my situation. I am glad that I took my DNA test and learned the truth about my life, but clearly Tom is not.

“When all was said and done,” Betty told us as we stood in the deserted room, “I asked him if he would take the DNA test again if he had the chance.”

Tom silently shook his head.

Thanks, Bill, for a very heartwarming story. It’s hard for me to tell exactly where Tom was in the many steps of the grieving process, but even though he was still on the negative side of accepting his story, it is hopeful that, if he is still with us, your friendship and understanding will be able to comfort him into accepting what happened, and that he will look positively on his life in the twilight of his years. The best to both of you.

When I started receiving matches from my dna they were all on my mothers side. It was a long time before matches to my dad’s side started to arrive, and they fit the paper trail. My great, great grandfather is Josiah Smith; a great name to research. I had my brother’s Y DNA tested and submitted the result to Smith’s Northeastern project two years ago. There he sits all alone with no group identified, and no one even remotely close on Family Tree DNA. We are beginning to wonder if back there somewhere there was a non paternal event. If this is the case I have not done any long research on that side of the family, because I can’t find Josiah before he showed up in census records in Vermont.

Not the same as being adopted or having your “father” not your biological father, but frustrating all the same.

Bill, while I feel sorry for what Tom has gone through emotionally, there’s a positive way to look at this experience. He spent 15 years producing what must be an impressive amount of research material on the family he thought was his. Despite his disappointment that it turned out not to be his own, it’s still important work and he should be proud of it. Hopefully the institution to which he donated it will make it available to others.

One of the things that separates REAL genealogists from amateur hobbyists is the ability to be as interested in other people’s ancestry as in their own. It’s a line you cross at some point in your research, when you realize that you can’t remember whether this particular family is one of your own or not. Consider, for example, the work of someone like Bob Anderson; where would the Great Migration Study be if he had only thought to research is own lines?

Hopefully Tom can get beyond resignation to a more positive outlook on this whole thing!

I feel for both Bill and Tom, though my feelings, as a biological child, can’t possibly be yours. I think one difficulty is that their adoptive parents weren’t honest, even if their motives were good. Even if they had told them, the response of the child can’t be predicted. I know two families who adopted one of their children, and lovingly told them so. In both cases, there was sturm und drang during adolescence over the issue. But one family was able to come through it and the adopted child is now, in her 40s, well integrated into her adoptive family. When she was college age, she searched out her birth parents, found them, was glad to know where her smile and her musical ability came from, and moved on. In the other family, even in childhood, the adoptive mother decided that every problem was because the child rejected her because she wasn’t his “real” mother. He too sought his birth mother at about the same age. He found her, but I’ve no idea if he’s still in touch with her. His adoption was just too much for him to accept, and, also in his 40s, he’s never felt part of the family he grew up in. I hope for him, and for Tom, that this will change.

After many years of researching my father’s line I learned, through DNA testing that the man I grew up with was not my biological father. At first I was surprised, then I was hurt, then I was curious. I was able to eventually find out who my biological father was and to find 3 new brothers who have accepted me with open arms. It is not easy when you are older, in my case 63, to discover your life was not as you thought. But..it is what it is and acceptance comes. The fun part is discovering all the new ancestors and their stories!!

We are more than the tabulation of our genes. Although he may not be related genetically, this is the family that shaped him emotionally.

Bill, please tell Tom to call the local library and “get his family back.” The “folks” in his research are still HIS family – if they hadn’t crossed the oceans to make the choices they did it means he wouldn’t be the person he was meant to be. It is the inherent flaw of genealogy that it is always somehow compelled to play that pretentious big brother to the truth that is “family history.” God speed my friend –

Our family relationships aren’t just based on genes. The pat of this story that captured me the most was this: “Betty told me that when she started dating Tom, she fell in love with his whole family. They all had a special bond, she said, and she very much wanted to be a part of that.” That bond meant that there was a family, and those bonds were built on the experiences and heritage, non-genetic though it may be, of the generations before. I hope that Tom comes to recognize that, and the good fortune he had to grow up in such a bond of love.

Although I wasn’t adopted, thanks to an experience several years ago I can totally relate to the feelings of one’s sense of self shifting at the news. “Betty” and I weren’t blood relatives but her mother’s people had been marrying my mother’s people for a dozen generations, so were had hundreds of cousins of one degree or another in common. She often talked about “Frank and Jane”, an aunt and uncle of her husband “Bill” who were both nearing 90 but were still as sharp as they’d been at 30 and 40. Jane was the repository of most of Bill’s family history back to the first immigrant ancestor, which meant nothing to me at the time.

Four years after Betty and I began collaborating on our shared connections, a distant cousin on my side also addicted to genealogy dropped the bombshell that Betty’s husband and my now-deceased father were 4th cousins NO removes through Dad’s paternal grandmother. In 20+ years of searching for her family, I’d only managed to determine her first and maiden names, but the documentation the cousin had gathered verified the relationship.

Oddly, other than Bill and I now knew we had an ancestor in common, the importance of this revelation didn’t hit me until a year later when I finally met Frank & Jane. Betty, Bill and I had arranged to meet them at their ancestral cemetery to photograph and catalog the stones. F & J, both dressed in jeans T-shirts and running shoes, were bouncing around the cem like teenagers. I’d gone over to Jane to introduce myself simply as “Betty & Bill’s friend Joanna”, but on taking Jane’s hand what came out instead was “I’m Joanna. You and my dad were 4th cousins”.

In that instant it dawned that Jane and I not only shared the genes of many of the cem’s inhabitants, but hers had been a huge family my dad and his two brothers, short on (known) relatives on their dad’s side, would’ve loved and visited often. I was aware that my sense of “family” had suddenly shifted and not in a good way, that Jane was a link to many generations of people I should’ve always known, or at least known about, but didn’t. That my once-full family tree was suddeny missing nearly half its branches. I came away that day with the sense that this must be how “new” adoptees feel on learning of blood relatives they never knew existed.

Again, I know this is not *exactly* the same as learning late in life that one is adopted, but close enough that I can totally relate to the feeling that one’s world has changed forever.

I’ve known I was adopted from my earliest memory. My parents told me the story of how they brought me home from the adoption agency instead of from the hospital. I grew up knowing and feeling I was different than my adopted mom and dad’s families. I never quite fit in, as much as I love them all. We did not share ethnicity, and it was strong on both sides of the family (dad grew up speaking French-Canadian, mom grew up speaking Portuguese). I have ALWAYS been in search for my blood. It has taken a while, but I have connected with my bio-dad and all my siblings. They have welcomed me with open arms and I love them all.

Bio-mom wants nothing to do with me, and before she would give me bio-dad’s name, made me promise not to contact my siblings on her side. Blackmail, for information I believe I am entitled to have. While she is alive I will keep my promise, but after she passes, all bets are off. I believe every person involved has the right to know their true history. I think my brother and sister have a right to know about me, as much as I had a right to know who I came from.

I understand it would be a shock to find out so late in life that you were adopted, but as an adult, you are far more equipped to handle that truth than a child, growing up wondering why you were given up, or knowing your parents tried for years to have their own child, but couldn’t, so adopted you instead. I am being a bit dramatic. As an adult I know they love me, and that those feelings are not so black and white. But when you are a small child, those are the feelings you have, no matter how many times they say they chose you.

My experience makes it difficult to understand why adults who find out their truth fall to pieces. I haven’t replaced my family now that I’ve found my bio-people. I now have two families! I don’t understand how one can just throw away a history because the blood isn’t what you thought it was–I research all four parents’ family history now! I don’t understand how one can know about siblings and not reach out to them. I waited years to contact my bio-dad, but realized that I would probably regret if he passed away before we connected.

Life it too short people. And the truth is the truth, you are who you are, both biologically and otherwise. It is truly a shame to waste time wallowing in self-pity when there are people you could be sharing some love with, or at least some good times.

Kathy – you have said it all so very well.