Many family history researchers are hard-pressed to find personal information, photographs, memorabilia, or heirlooms to treasure and preserve. I am not one of them, and yet I seem to have a remarkable supply of “memories of things unknown,” the scraps of someone’s attempt to memorialize a moment or a personality in a manner obvious to the author but obscure to later generations. I have stacks of unmarked photos of unnamed family members, locations, cattle, horses, barn cats, and especially Dalmatian dogs.

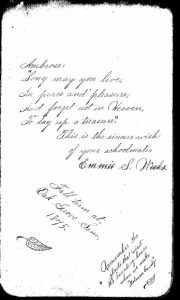

My great-grandfather Ambrose Church’s autograph book from his school days at the Oak Grove Seminary in Vassalboro, Maine – a girls’ school founded by the Society of Friends, but open as co-ed to local children – is a case in point.  It is a memory book of days long forgotten, as unfamiliar to me as the school itself, and filled with wonderful artwork, enviable script handwriting, inspiring messages, and hints at fun events between 1875 and 1878. Emmie S. Weeks wrote during the Fall Term of 1875: “Remember the ghosts that visit the boarding house when we make molasses candy.” It’s easier to hear the voices of those friends in these pages than the echo of an earnest moo or a friendly woof in a black and white photo!

It is a memory book of days long forgotten, as unfamiliar to me as the school itself, and filled with wonderful artwork, enviable script handwriting, inspiring messages, and hints at fun events between 1875 and 1878. Emmie S. Weeks wrote during the Fall Term of 1875: “Remember the ghosts that visit the boarding house when we make molasses candy.” It’s easier to hear the voices of those friends in these pages than the echo of an earnest moo or a friendly woof in a black and white photo!

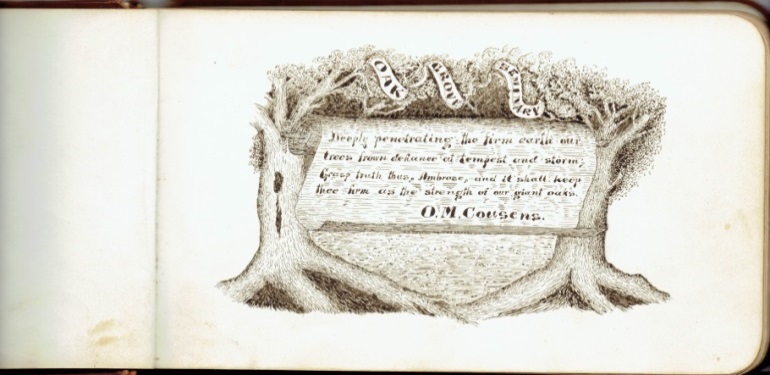

At first glance, I thought the book was a collection of memories of unknown things, fascinating in itself but problematic on its face. A few names were recognizable as maternal cousins, but who was Emmie Weeks who made molasses candy or O.M. Cousens who drew beautiful trees? What was “the week of Thanksgiving 1875,” referred to so many times in its pages? After a second glance and some online research, I found a similar album online which belonged to Ambrose’s brother George!

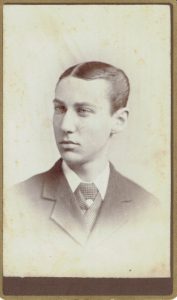

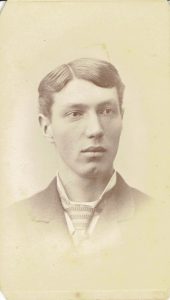

Cousin Charles W. Sawtelle wrote on 7 February 1877: “Remember out in the entry at singing school North Sidney the Friday eve before Thanksgiving ’76.” (Did they sneak a smoke?) And “Remember the short comb.” From their photos, neither Ambrose nor George had enough hair for a long one!

City directories and census records gave very little information about the friends and relatives signing Ambrose’s book, and I was surprised at how quickly they “disappeared” after leaving the school. In 1875, O.M. Cousens was the principal of the school who drew the detailed trees on the first page. Florence and Charles Sawtelle were siblings and Ambrose’s cousins, but Emmie Weeks is still a blank. Local newspapers of the time are silent on events of that popular Thanksgiving week, and I lack family diaries that might explain everything. Research at the Vassalboro Historical Society revealed that in all probability the school did not produce yearbooks for the years 1875–78. In fact, the school’s spring term 1875 was only five weeks long because of a “violent epidemic disease.”

The autograph book is also a small view of Ambrose’s life as a teenager, his community, and the society in which he moved. He was only fourteen when the book begins in 1875, only 17 when he finished at the Dirigo Business College in 1878. How many teens now can make molasses candy, both pulled and sponge? For that matter, in these days when schools are eliminating courses in penmanship, how many of us can write legibly, let alone in script?

Undoubtedly because Oak Grove Seminary was founded as a Quaker school, there are many inspirational messages and reminders of Christian duty. “Seek ye the Lord while He may be found. Call ye upon him while He is near. Remember me as your true friend. Ewing Bailey.” While Ewing Bailey is personally another blank, his reference to bass fishing “down on the pond” is enlightening.

This book of so many memories has reminded me to look more closely at the days of my own life to recognize what will be of future value. It is sad that there are many people who will be forgotten in pages like these, especially in a digital age lacking print materials, even though such recorded sentiments can reveal much of their personalities if we only pay attention.

One line written on 26 April 1876 by Dirigo Business College’s schoolmaster, Frank Marden, is particularly poignant and prophetic: “May your life have just enough sorrow to temper the glare of the sun.” Ambrose Church’s future had both sun and sorrow, but for only twenty years: he died on 9 September 1896, at age 34, of “pulmonary consumption” (tuberculosis), leaving a wife and thirteen-year-old son, my grandfather Rex Church.

We, the family researchers, understand the fallacy of the common attitude that “of course we’ll remember these people.” We should never become memories of people unknown, nothing more than signatures on a page or next to a hashtag. While we may not seek fame, infamy, immortality, or notoriety, I believe it is our responsibility to provide our descendants enough information to know who we are, and how we fit into our families and communities.

HI Jan

I had family in Vassalboro, I wonder if you could check the book for any Stevens or Reeds that may have signed it.

Thank you

Lisa (Whitcomb) Huckins

Hi Lisa, I checked the book, and there is only a William Reid of Augusta who signed it, no Stevens at all. Neither name appears in George’s autograph book as it appears online. Sorry! However, I have many Reeds/Reads in my family, Lees, Libbys, and Browns in Vassalborough, and a few Stevens in the Augusta area. There might be common ancestors!

In my (ha!) spare time, I now fully intend to dig out my great-grandmother’s autograph books from Oberlin, Ohio, late 1860s. Your article inspires me–who might Google help me identify among the signers & poetasters? Thanks!

Bob Leutner

Iowa City IA

Jane, go to Googlebooks advanced and search the phrase “May your life have just enough sorrow to temper the glare of the sun.” You will find the source of the phrase in several books. I recently did this for a phrase written by one of my great great grandmothers and found the book from which she had copied it.

As always, another excellent article about your family! Thought provoking! Thank you Janet.

Jan, so many of your posts trigger thoughts of stories I can pass on to my grandchildren. They also make me think about the assumptions our parents and grandparents made, and the assumptions we make in turn. I have to laugh, because many of those assumptions become part of my stories! When I went to school, we were required to have intensive study of cursive writing, as it was assumed that no one could succeed without being able to write legibly. Well, that training ended in eighth grade, and the handwriting of nearly every single one of us deteriorated dramatically over summer break! Then we each began experimenting with letter forms, and by high school graduation had developed a reasonably legible individual style that bore little resemblance to the rigidly enforced “standard” we’d been taught. And oh, my, the worried fuss by elders about lack of cursive skills among my grandchildren’s generation as they picked up keyboarding in grammar school! Now those children are all in their mid to late teens, and — each has developed a perfectly legible, highly individual cursive style. , What I find interesting is that their styles, though individual, are oddly peculiarly similar overall to mine and to my children’s handwriting! I love being made to think about that, and to recognize it as part of the heritage (whether genetic or cultural) being passed down through my family. Now I have to go dig out some old letters and look at the writing– who knows how long this has been going on, even with changes in letter forms?

My grandfather was the headmaster of the oak grove school in 1914. I have family pictures and his diary from that time. I would like to meet someone there and share.