When researching a family, one can quickly become focused on names, birthdates, and death dates. It is easy to get caught up on going as far back as possible until reaching the metaphorical brick wall, and being left with a “well, what do I do now?” mentality. Seventeenth-century immigrants can be incredibly difficult to trace and track, but learning about them in public records can help add meaning and information about their lives.

Our database Middlesex County, MA: Abstracts of Court Records, 1643-1674, digitized from the Society’s R. Stanton Avery Special Collections, can provide interesting information about seventeenth-century New Englanders beyond their vital records.

Though some of the records are brief, such as a one-line abstract indicating that an individual gave testimony, other records are more detailed. On 20 April 1654, 28-year-old Robert Twelves appeared before the court to state that though he came to New England to serve as an indentured servant to a Mr. Hobson for three years, he was able to pay off his term after a year and a half.

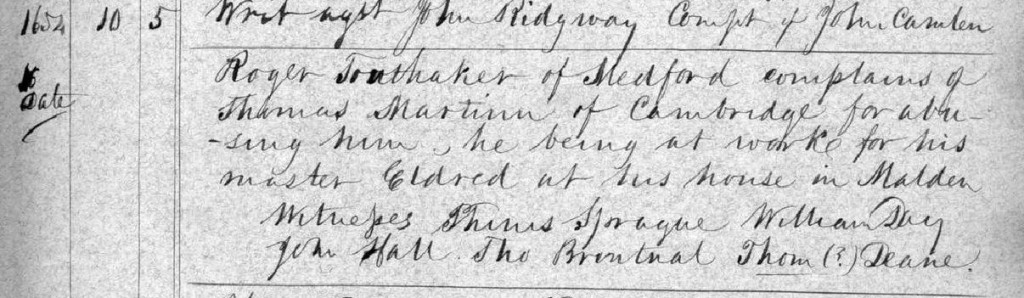

These records also depict the struggles and challenges of living in early New England. In 1654, an indentured servant, Roger Touthaker of Medford, filed a complaint of abuse against a Thomas Martin of Cambridge while he was working in Malden for his master, a Mr. Eldred.

Recently, I used the court abstracts to provide a possible answer to a research question. George Lillie of Reading in Middlesex County married Hannah Smith in Reading in 1659. According to previous genealogies compiled by the Lillie family, Hannah was the daughter of Francis Smith of Watertown and Reading. However, Great Migration series author Robert Charles Anderson provides evidence that she was likely not Francis’s daughter. That left the question: who was Hannah (Smith) Lillie?

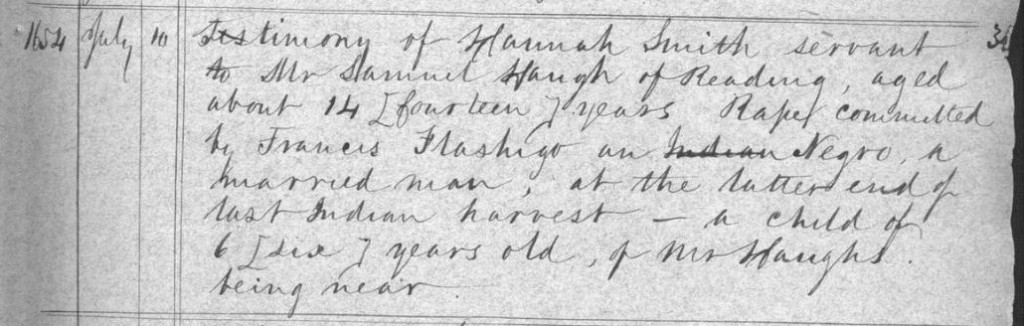

The Middlesex County, MA: Abstracts of Court Records, 1643-1674 database provided a potential solution to this question. On 10 July 1654, fourteen-year-old Hannah Smith, servant of Mr. Samuel Haugh of Reading, gave testimony before the court about an assault on her by Francis Flashigo. On 31 May 1656, Hannah Smith, aged about 16, appears in court to state that she was living with Goodman Press.

If this Hannah Smith was fourteen in 1654, she would have been about nineteen in 1659, when she married George Lillie. This is about the average age of a first marriage in the seventeenth century, and her residence in Reading makes it possible that she is the first wife of George Lillie. Though these court records do not firmly link this Hannah Smith to George, the court records provide potential solutions to brick walls as well as insights into the lives of early Middlesex County settlers.

It sends a shudder through me to think that I might have claimed a branch of ancestors who are not my own, that I might one day come across a document that upends it all. In fact, there is a Lillie in there somewhere and I’m going to go look it up right now!

Having to undo an ancestor is one of the most frustrating problems I’ve encountered. A William Knapp of Watertown had a daughter named Anne who married a Thomas Philbrick. So say many, many records. However, William Knapp’s will states that the share of his estate meant for his daughter Anne should go to the children of John Philbrick, Thomas’s older brother. I still don’t know who Thomas married. And I had spent over a week sorting out William Knapp, too.

These are definitely interesting abstracts. I took a quick look today, just to see some of the Peirce surname records. One had two pages of names of testators regarding the illegitimate child of an Elizabeth Wells and James Tufts, son of Peter Tufts and Mary Peirce (dau. of Thomas Peirce of Charlestown). The records give all the names along with their ages, and sometimes relationships. All very useful, and in this case, a very intriguing story too.

Middlesex, Co., MA – Abstracts of court records, 1643-1674, Vol. 2 p. 80-81

Hurray for Mr. Wyman! Without whose inspired deligence over several winter months, we wouldn’t have such a resource. Especially as it reflects the ORIGINAL ordering of the material, rather than John Noble’s circa 1900 “rational” reorganization of it.

I had the pleasure of working directly with the manuscript on Wednesday evenings for several weeks, learning how TBW handled the material, etc. It was a joy to see it all again in clear relief as a pic rather than that less than useful OCR edition that was first up.

NOTE: The vast majority of Suffolk and Middlesex files remain locked away. The only substantial Suffolk publication remains Sam Morison’s 2 volumes in the Colonial Society of Massachusetts series from 1933. They are on the shelves, completely under utilized. As they are now out of copyright, GET THEM UP AS SEARCHABLE DATABASES.