Vita Brevis readers are likely all too familiar with the problem of brick walls in genealogical research. Many are aware of the uses of probate and estate records, but what if your ancestors are not to be found in the probate records of the area where they died? There can be any number of reasons, for economic conditions in the colonial and early Federal period were often unstable, and a family could find itself experiencing periods of both comfort and destitution at one point or another. Fortunately, there are a number of techniques to track less wealthy ancestors, both in the interest of making family connections and learning something of the reality of their lives.

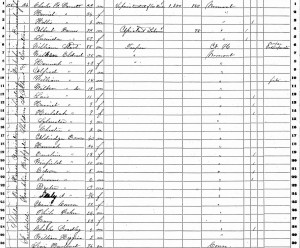

Building on NEHGS researcher Zachary Garceau’s previous post on criminals, you can also generally identify impoverished persons in the early records of the U.S. Census via entries designating poor houses or almshouses. Sometimes these institutions will be identified in the left-hand column of the census, as in the above example from the 1860 U.S. Census for Sheldon in Franklin County, Vermont. You can see that this page was dedicated to the Sheldon Poor House Association and that Charles F. Barnett, superintendent of the poor house, was listed as the head of household along with his family. In this example, the designation of “pauper” is found in the occupation column.[1]

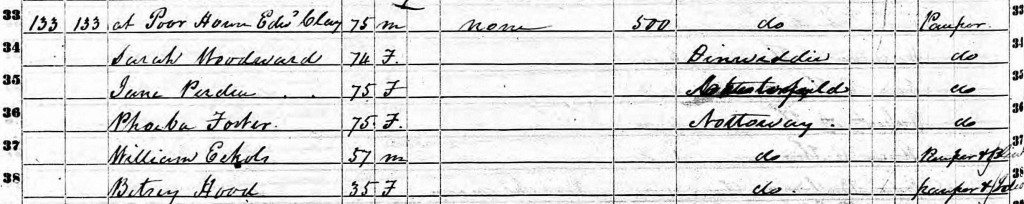

At other times, the household is designated as a poor house in the line intended for the name of the head of household. For example, in the 1850 U.S. Census for Nottoway, Virginia, a line reads: “at Poor House Edward Clay” before listing the other residents of the poorhouse below in the same household unit. Each of these persons was designated as having no occupation and under the column for “condition” they were described variously as “pauper,” “pauper and blind,” and “pauper and idiot.”[2] These designations reveal assumptions made regarding the nature of pauperism and disability and belie the reality of the nineteenth century reform era’s poor relief system.

There can also be found some more specific lists of poor house residents that have been digitized for your convenience. Ancestry’s database New York, Census of Inmates in Almshouses and Poorhouses, 1830-1920 could be particularly useful if you are trying to locate elusive immigrant or other ancestors who might have passed through the state’s sizeable poor relief system. Ancestry also offers another database, U.S. Federal Census – 1880 Schedules of Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes, which contains lists of the impoverished, among others.

Once you have determined your ancestors were associated with a poor house or if you have lost track of them in other records, you can search for records of the Overseers of the Poor and other similar organizations to try and find more information about their circumstances and their time in (and aid from) the almshouse. Unfortunately, most of these records have not been digitized and might be more difficult to access. Members of American Ancestors have the benefit of one rare digitized collection, Portsmouth, N.H.: Records of the Overseers of the Poor, 1817-1838. The database contains record abstracts of persons who received items and services from the Overseers and can be used to determine the nature of an ancestor’s need and/or the length of his or her stay.

One page of the record from 1838 (at left), the final year of the collection, gives you a good idea of the kind of information you can gather from these records. We can see that a number of people needed board for a few weeks, likely due to poverty, especially in the case of the women who are listed with children whose fathers are absent. Others likely found themselves in the poor house due to illness, as you can also see in this example. One woman, Margery Brown, was boarded for three weeks because of her sickness, which also claimed her life. The Overseers recorded the costs of her coffin and funeral expenses, noting a death that might not be found in other records. Other wards of the Overseers only needed temporary aid, like the three individuals at the bottom of the page who were given cord wood. There are two other items of note on this page. Descendants of John Barwin will be interested to learn that the Overseers paid for his travel to Newburyport after his sixteen week and four day stay in the poor house. They could use this information to continue searching for him in the records of that town. Finally, we learn that Mary Elizabeth Smith, who received board and clothing, was the daughter of the Theodate Smith who had spent nearly thirteen weeks in the poor house the previous year.[3]

At our library we have numerous other records of the Overseers of the Poor for various towns and states, should you be interested in preparing to research an impoverished ancestor. You can search our library catalog for “Overseers of the Poor” or “poor house” to get a sense of our holdings before you plan your visit. Other resources to try are the local libraries and historical societies for the areas in which your ancestor lived. They may have records in print or on microfilm that staff can search for you or you can visit and browse yourself. Another good resource to browse for poor house records and history is the website, The Poorhouse Story, which is dedicated to resurrecting poor houses from historical obscurity. Poverty might make an ancestor difficult to find through more traditional sources, but, fortunately, the system of nineteenth-century poor relief left quite a few records that can be useful in your genealogical pursuits.

Notes

[1] Sheldon Poor House Association, Year: 1860; Census Place: Sheldon, Franklin, Vermont; Roll: M653_1321; Page: 609; Image: 623; Family History Library Film: 805321. Ancestry.com. 1860 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009.

[2] Nottoway Poor House, Year: 1850; Census Place: Nottoway, Virginia; Roll: M432_965; Page: 373B; Image: 202. Ancestry.com. 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Provo: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009.

[3] Record 1838, Page 496, Portsmouth, NH: Records of the Overseers of the Poor, 1817-1838 Online database. AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2012. (From records held by the New Hampshire State Archives, Family History Library film 15284–15293.)

Warning outs have been so invaluable to my research as well!

All these stories are deeply touching, but I was especially taken by the first example when I realized that the Superintendent of the Sudbury Poor House was himself 88 years old, and his wife 86. Possibly a respected town elder whose dignity was saved by making him Superintendent? Or was this common, a task taken on by an elder? There is a child age 4 listed with their surname, followed by a young couple with a similar but different surname who appear to be helpers. Was the child mistakenly given the elder couple’s name? Or if not, what was the relationship? Was he perhaps the younger couple’s child, and the last name confounded? There is a story here; I wonder if the town records might have information to flesh it out a bit.

My own family has a similar story, some three-fourths of a century later, in Idaho. My mother’s parents lost their farm early in the Great Depression. He worked for the county roads dept for some years, but lost his job when he lost sight in one eye to an injury. In those days, there was no workers compensation. He and my grandmother jointly took on the Superintendency of the “Poor House”. Basically, this meant he was the janitor and handyman and, with an assistant, she cooked and cleaned. They also raised two of their grandchildren, until my grandfather died and my grandmother’s health was too impaired.

It never occurred to me that there might be records specifically related to this period of their lives. This post was illuminating, not only for my early New England people, but for a generation I remember. Now I have a whole new set of to-dos, and need to plan another trip to Idaho, this time to look at county and land records.

Annie, I agree that it would be interesting to look more into Barnett and discover how he came to be superintendent. I think with an organization as big as the Sheldon Poor House Association it was likely a respected position for an older man to hold or he could have been instrumental in the organization for a number of years. He likely wasn’t of pauper status as the census records property for him at the top of the page. I do think this would vary depending on the location of the poor house, and you are right that town records would likely be very helpful in sorting that out. Regarding the child, I think more than likely it was a grandchild of his, but that raises questions about what happened to the parents. They also certainly could also have adopted in some capacity a poor child given how many they probably encountered in their line of work!

Your example from your own family history is really quite interesting, though, and raises questions about the nature and structure of poor relief systems on the frontier and other, less populated and less established, areas. Certainly it must have been quite a gamble for many families to strike out to the edges of settlement, and just as likely to end in hardship as success, so it would be interesting to do more research about poor houses in those areas. I hope your new searches prove fruitful!

I just found a video on YouTube my first time ever seeing or hearing of this poor house those poor people it’s truly sad and it was heartbreaking to watch

After years of vainly searching more traditional records, I finally hit pay dirt by consulting Town Council records for where my ancestors lived. They received poor relief and more: one direct and one collateral relative appear in these records for having illegitimate children. When these folks died, no formal record was made at the town level of their deaths or where they were buried. Gravestones? I wish! I am grateful to the people at West Greenwich (RI) Town Hall for allowing me to peruse their very old records; and to Dr. Ruth Wallis Herndon for writing the book *Unwelcome Americans: Living on the Margin in Early New England* — which gave me the context to understand my ancestors’ situation.

Elaine, what a perfect example of the utility of poor relief records and scouring those tricky, old records! You’ve also hit on another issue of the burial of poor persons. While the woman in the Portsmouth records appears to have received a proper burial, there is no telling how many destitute people have been lost in the records for improper or anonymous burials. Another book you might enjoy that gives context for marginal and transient people is the volume that I mention in the first reply above: Robert Love’s Warnings. It paints a fascinating picture of Boston in the eighteenth century and the types of people that passed through.

Thank you for recommending Robert Love’s Warnings. I just sampled some of its pages at Amazon.com, and it looks really good!

I have also found information on poor relief in newspapers. The poor house or poor farm expenditures were public records. I have found them printed in the local papers quarterly or yearly. The name of each recipient, time at poor house and the cost to the local authorities is given. In my own family, young children seemed to have moved in and out of the poor house after their mother died. For a time their father was with them. They had several relatives in the area. Was no one in a position to help them?

I have found indirect relatives in both a juvenile reform institution in NY at age 9 and a poor house in Montana, where he died. The former was a boy whose father died and mother remarried and evidently scattered the children. I haven’t been able to trace him beyond the institution to know what he made of his life. His sister is my ancestor. Very hard to trace children that have been farmed out. The latter certainly had relatives who could take him in and evidently did according to previous censuses, but they don’t always know the situation.