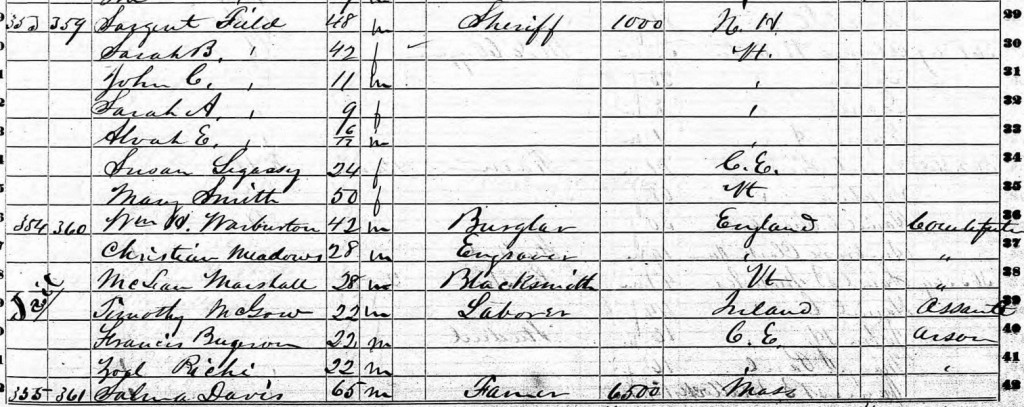

The Federal Census of the United States was established to accurately list the nation’s citizens, including those serving time in jail. In June 1850, men by the name of Christian Meadows and William H. Warburton (better known by his alias of “Bristol Bill”) were found guilty of counterfeiting currency at Groton, Vermont.[1] Meadows appears in the 1850 Census living in Danville, Caledonia County, with his condition listed as “counterfeiter.” Directly above Meadows is Warburton, whose profession is listed simply as “burglar.” The word “jail” is scrawled across the column generally reserved for the dwelling and family numbers, making it abundantly clear where the men are residing. In the household before the prisoners, we also find a “Sargent Field,” whose occupation is given as sheriff, showing that the man responsible for capturing criminals lived with his family next door to the building where they were held.[2]

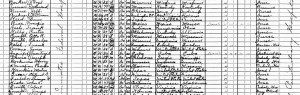

In the 1860 Federal Census, another small group of men between the ages of 19 and 66 are listed together, this time without occupations, in Jacksonville, Alabama. In the column beside the names of these seemingly unrelated men, born in various locations, are the words “prisoners in jail.” There is not any indication as to the nature of the crimes which landed these men in prison. Once again, just two houses from the jail is the local sheriff, showing that when it comes to criminals, the law was never too far away.[3]

In 1880, enumerators were provided a separate supplemental sheet with the words “inhabitants in prison” written across the top. These sheets were different from the standard Census of 1880 in that the age and occupation of an individual was not recorded; instead, this information was replaced with length of sentence and the nature of the prisoners’ crime. In one example, Thomas and Edward Reilly of Jersey City in Hudson County, New Jersey, were imprisoned for assault and disorderly conduct respectively.[4] However, if these two men were related, they were not sentenced on the same day, suggesting separate arrests.

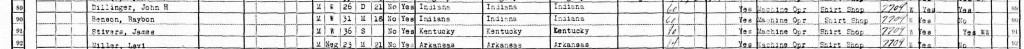

In the 1920s and ‘30s, American criminals began to gain a larger degree of fame than ever before, and census records from this period reveal a great deal about their lives in prison. For instance, much can be learned from a 1930 record from the United States Penitentiary Hospital in Leavenworth, Kansas. Among the inhabitants listed in this hospital is Lloyd Barker, a member of the notorious Barker-Karpis Gang. The words “Inmates Federal Hospital” are written in the column reserved for the relationship of an individual to the head of the household. Interestingly, while most of those listed on this page have their occupation listed as “none,” interspersed throughout the page are others with a wide range of occupations, among them Nurse, “Runner,” “Barber Hos.,” “Orderly Hos.,” “Electrical Hos.,” Drug Clerk, “Laundry Hos.,” and Cook.[5] It appears that these prison employees may have been inaccurately labeled as inmates due to their close proximity to prisoners on the census record.

Another notorious criminal may be found 450 miles away from Leavenworth in the Indiana State Prison. Listed towards the bottom of a type-written census sheet, a relatively rare find, is a man by the name of John H. Dillinger.[6] Much like those mentioned above and below him in this record, Dillinger was labeled as a machine operator at a shirt shop, showing that inmates were put to work while serving their time. Mixed within this list of shirt shop employees, we also find a hospital porter and attendant mentioned. One cannot help but envision an enumerator, clipboard in hand, walking through the halls of the prison, recording information on those he encounters through his journey, leading to this seemingly random order of individuals.

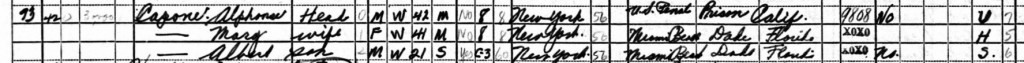

In Miami Beach, Florida, in 1940, we find perhaps the most well-known criminal in American history, Alphonse “Al” Capone, living with his wife and son. Here, he is seen living the life of a free man after being paroled on 16 November 1939. Because he was imprisoned in 1932 and paroled in 1939, there are not any census records showing Capone during his time in prison; however, the 1940 Census asks individuals where they were residing in on 1 April 1935. In the case of Capone, who was being held at Alcatraz Federal Prison, he was recorded as residing at U.S. Penal Prison, California.[7]

The United States Census has always acted as a means of recording those who are living throughout the country. As shown in these records, those who were serving time in prison were also recorded, and the information provided by these records is a valuable resource for researchers and historians.

Notes

[1] “Announcement,” Vermont Journal, 21 June 1850, p. 2.

[2] Household of William H. Warburton, Danville, Caledonia Co., Vermont, 1850 United States Census, Roll: M432_922; Page: 235A; Image: 464.

[3] Household of H. H. Sutton, Jacksonville, Alabama, 1860 United States Census, Roll: M653_4; Page: 295; Image: 11; Family History Library Film: 803004.

[4] 1880 United States Prison Enumeration Sheet, 1880 Schedules of Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes, ancestry.com.

[5] United States Penitentiary Hospital, Leavenworth Co., Kansas, 1930 United States Census, Roll:707; Page: 1A; Enumeration District: 0018;Image: 1177.0; FHL microfilm: 2340442.

[6] Indiana State Prison, Michigan City, Laporte, Indiana, 1930 United States Census, Roll: 604; Page: 12B; Enumeration District: 0021; Image: 96.0; FHL microfilm: 2340339.

[7] Household of Alphonse Capone, Miami Beach, Dade, Florida, 1940 United States Census, Roll: T627_581; Page: 2A; Enumeration District: 13-42A.

Zach, whenever I see your name on a Vita Brevis post, I know I can look forward to a slightly different (and informative) take on things. I loved this- especially the enumerator who took quite literally the “occupations” of those Vermont inmates! I would suggest, though, that the people in the Indiana prison may well have been prisoners who had been given duties within the facility. That is not an unusual situation, then as now.

Annie,

I appreciate that! I would also agree that the inmates in Indiana were likely put to work as part of their sentence or would given those duties. I meant for it to sound as though this was not their employment prior to their sentencing, however, now that you mention it, I can definitely see how I could have phrased that better. Thanks for the feedback!

I agree with Annie. The 1930 IN state prison shows a similar pattern, with the inmates you show working in the “shirt shop.” I’d guess they were making shirts for other inmates, including the numbers that identified them. Not a particularly marketable skill once they got out.

The lack of the 1890 census causes a major problem for me in this regard. I’ve mentioned in other VB posts my g grandfather who in March 1890 was convicted of murder in Wisconsin and sentenced to “life at hard labor” in the Wisconsin state penitentiary at Waupun. The prison records don’t survive, but he should have been enumerated in the federal census that year. He was pardoned unconditionally in January 1895, so does not show up in the prison in the Wisconsin state census that year, as it was taken in the summer. He’d returned to his home and children by then, and shows up there. I would have liked to see the 1890 census, just in case it mentioned the kind of hard labor they had a 40+ year old farmer doing. The town of Waupun was famous for its stone quarry, so it’s possible the prisoners were doing stonework. The prison had only been open about five years when he was sent there, and the original heavy stone gate is still visible in the prison’s home page.

Until recently you could be imprisoned in the State of Maine and other New

England states for debt and even tax collectors could be imprisioned if they did not collect all of the tax monies owed to the town. I wonder how the census takers in 1800 would have “enumerated” the case of Ephraim Ballard ….who found himself imprisioned for both offences at separate times as noted in the diary of his spouse, Martha Moore Ballard !

Half of my wife’s ancestors lived in Danville, VT, but fortunately, none of them had appeared on the Census as residing in the Danville Jail. And a small jail it was.

Very interesting! Have you come across similar listings in state census records? I found my gg uncle in the 1910 census in a prison work camp.

I used the same approach for identifying “inmates” of our local county orphanage over time.

So true …not only “orphanage inmates” but residents of “poor farms” , “mental institutions ” and etc. , could be as well identified from such census roles. Black sheeps do emerge from such uncensured, censured logs !

My distant relative’s husband was one of the criminals in the infamous Boston Brinks robbery. My research into him via the census starting in 1920, he was in one prison or another so the newspaper reports on him were quite accurate!