Colonial Massachusetts records are a family historian’s dream come true. From the beginning, early Bay colonists meticulously tracked the goings on of their communities, leaving records of government and community alike. These habits have resulted in a veritable trove of records available for genealogical pursuit, mostly aptly demonstrated in the large Massachusetts Vital Records to 1850 collection. However, vital records were not the only documents that these early settlers left behind. Surviving court records for some early Massachusetts counties are quite detailed; despite the wealth of information they contain, they are often overlooked by family historians.

Colonial Massachusetts records are a family historian’s dream come true. From the beginning, early Bay colonists meticulously tracked the goings on of their communities, leaving records of government and community alike. These habits have resulted in a veritable trove of records available for genealogical pursuit, mostly aptly demonstrated in the large Massachusetts Vital Records to 1850 collection. However, vital records were not the only documents that these early settlers left behind. Surviving court records for some early Massachusetts counties are quite detailed; despite the wealth of information they contain, they are often overlooked by family historians.

These court records exist in a variety of formats, most often in microfilm collections, but also occasionally in published transcriptions or abstracts. Fortunately for members of American Ancestors, there are a number of court record collections for early Massachusetts and Connecticut that have been digitized, some of which are searchable for more readily available access. In particular, our collection of the records of the Plymouth County (Massachusetts) Court of General Sessions and Common Pleas spans the period 1686-1859.[i] The categories of cases contained within these records include petty crimes, community disputes, financial disagreements, fornication and illegitimacy prosecutions, and some probate settlements or amendments.

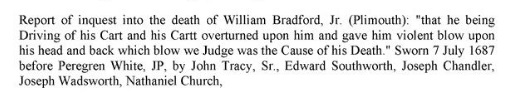

It can often be difficult to know how to use these records in genealogical research, so as a demonstration I chose a few examples from the first volume of the Plymouth County collection. Vital records are often the most sought-after data for genealogical research, and court records can be used as substitutes in some cases. Within this collection you will find investigations into suspicious deaths, such as that of William Bradford, Jr., who was killed after the cart he was driving overturned in 1687[ii]:

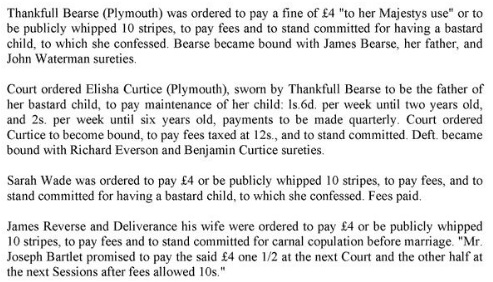

Many readers unfamiliar with early Massachusetts court records might be surprised to discover the number of individuals prosecuted for having children out of wedlock. In addition to offering a fascinating insight into the personal relationships of these early settlers, these cases are sometimes the only record of the births of illegitimate children, births which often were not recorded in the official registers. Additionally, the presentment of married couples whose first child was born too early can help confirm your lineage if you notice discrepancies between the marriage date of a couple and the birth of their first child[iii]:

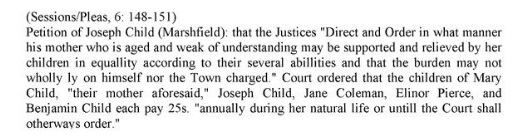

Lastly, there are a number of references to probate records and the support of elderly parents in these court records that can help piece together family relationships. In this example from the March 1698/99 meeting, you can see that Mary Child’s adult children were Joseph Child, Jane Coleman, Elinor Pierce, and Benjamin Child[iv]:

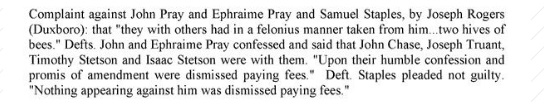

These records can also add biographical narrative to your family history. Locating your ancestors in court proceedings allows you a rare insight into their everyday lives and situates them within their community and time in a way that is unique to court records. Who knows, maybe you will find within your own early Massachusetts ancestry a gem like this daring scene from the Pray and Staples family history[v]:

Notes

[i] Information, Plymouth Court Records, 1686-1859, AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2008.

[ii] Plymouth Court Records, 1686-1859, vol. 1, p. 4. CD-ROM. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2002. Copyright, 2002, Pilgrim Society. (Online database. AmericanAncestors.org. New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2008.)

[iii] Plymouth Court Records, 1686-1859, 1: 74.

[iv] Plymouth Court Records, 1686-1859, 1: 35.

[v] Plymouth Court Records, 1686-1859, 1: 65.

On the darker side…. such records were kept to make sure that the Puritan oligarchy had total control over the populations that they governed in much of southern New England. Any deviation from the blue codes / standing orders of the day were quickly suppressed. If deviant behavior persisted ….such as failure to follow the rules of the sabbath (showing mirth, failure to attend the day -long meeting house services or even breaking the “nooning ” ) such deviants were considered possessed by the “devil” and for the good of the community had to be banished or even murdered. I actually compared the Blue Laws of Anglican Virginia with that of the Standing Orders of Puritan Connecticut (both dating about 1680). For the same offence…. in Virginia, if you could not pay a fine you got your head pinned to the stock ; in Connecticut , you would have had your head on the “chopping block”!