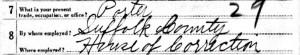

World War I Draft Registration Cards can be filled with useful and pertinent information about our ancestors. They can show us birthplaces, birthdates, parents’ nationalities, height, weight, hair color, and eye color. Additionally, occupations are shown on these draft cards, and can also be an invaluable resource. Was your ancestor a porter at the Suffolk County House of Corrections,

World War I Draft Registration Cards can be filled with useful and pertinent information about our ancestors. They can show us birthplaces, birthdates, parents’ nationalities, height, weight, hair color, and eye color. Additionally, occupations are shown on these draft cards, and can also be an invaluable resource. Was your ancestor a porter at the Suffolk County House of Corrections,

![]() a student at an automobile school,

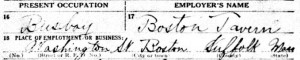

a student at an automobile school,

or a busboy at the Boston Tavern on Washington Street? This information appears as part of the draft registration process.

or a busboy at the Boston Tavern on Washington Street? This information appears as part of the draft registration process.

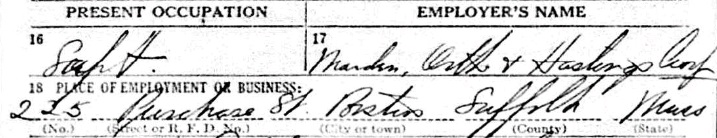

Recently, while researching the Hastings line in Massachusetts, I came across Arthur Henry Hastings’ World War I Draft Registration Card at Ancestry.com. In this instance, I realized that Arthur Hastings was employed at Marden, Orth & Hastings Corporation at 225 Purchase Street in Boston.

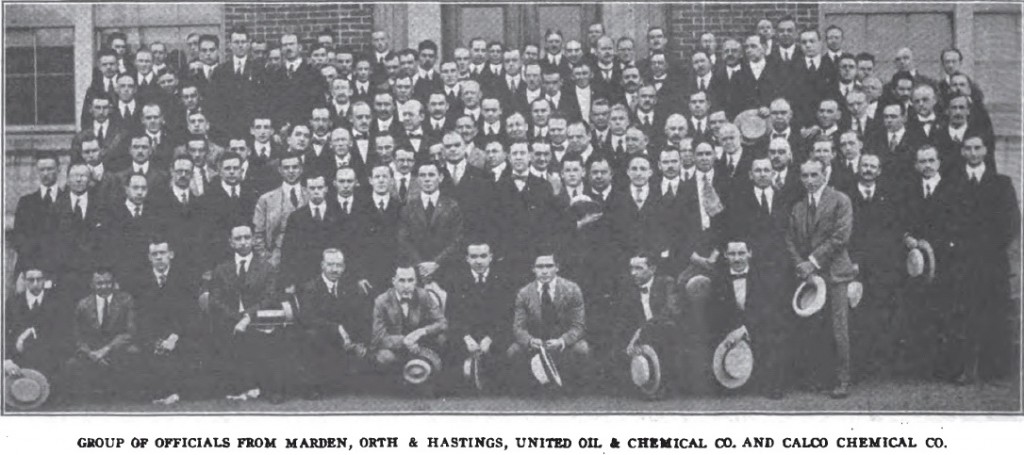

Did a Hastings family member start this company? Was the family that I was performing this research for aware of this company? I was able to search through business journals, textile publications, patent records, and advertisements to find out that Marden, Orth & Hastings Corp. was founded by James A. Murdock in 1837. Mountford S. Orth was a direct descendant of James A. Murdock, and he, along with Frank W. Marden and Walter Oliver Hastings (Arthur Henry Hastings’ brother), took over the business in 1906. The company was very successful and had offices in Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Seattle, St. Louis, Louisville, Bound Brook (New Jersey), Cincinnati, and San Francisco. Marden, Orth & Hastings dealt mainly with processing oils for the leather, paint, and textile industries, and stocked the tanning oils, extracts, and greases used in these businesses.

Many different kinds of leather characterized the Boston market in the early twentieth century; tanners were firm on their prices and buyers were unable to buy leather on their own terms.[1] A rising market in Boston in 1922 benefited both tanners and shoe manufacturers, as buyers were obliged to figure ahead on supplies, and shoe retailers and jobbers placed larger orders instead of buying small lots in anticipation of lower prices.[2] More boots were produced in 1922 than the previous year, but the bulk of the shoes produced were oxfords. Marden, Orth & Hastings lasted until the stock market crash in 1929. I was able to find a picture of the company from the August 1918 Textile World Journal (see above).

This was great information for the family I was performing research for, and showed me a valuable lesson when looking through military draft registration cards: there is much more information on these records than simply when and where a family member may have registered for a military draft. Pay close attention to the other details and you may find out some valuable information that was previously unknown to your family.

Notes

[1] Shoe and Leather Reporter, 19 October 1922, p. 33.

[2] Ibid.

Thank you for your insights regarding information we may glean from unexpected sources such as draft registrations. Very helpful!

One little question — I think the first snippet may refer to a “porter” rather than a “pastor” at the house of corrections. It is my understanding that the occupation of porter, while now almost fallen into disuse except as a mover of luggage, used to refer to a wider scope of cleaning and/or maintenance jobs. The handwriting reads more like porter than pastor to me, and prison clergy would normally be referred to as chaplains, not pastors.

Fixed!

Scott, I believe it was you some time ago who mentioned the conundrum of knowing/researching which John Smith was which in early Cape research. Do you happen to have a source that might help spell that out? I researched the “green books” at the Sturgis, but want to make sure I have seen everything I can possibly gather.

A bonus: one sees an authentic image of the registrant’s signature!

Has anyone seen any work on various handwriting styles and conventions, as well as the methods that were taught….or were there earlier methods, such as the Palmer method that I was drilled in?

Yes, Jane, if you google “history of handwriting” there are several books on the subject.

Great point for those looking for individual information. I have resolved a series of roadblocks by reviewing the Civil War enlistment records of 4 g-g-uncles. Also,consider Civil War discharge certificates and Pension applications for data from 1861 on.

I found the WW I draft registration cards for both my grandfathers. In addition to their signatures–the only one I have found for my paternal grandfather–I learned exactly where they were on that date. I knew my maternal grandfather, but my paternal grandfather died before I was born, so I learned more from his card. His job as a civil engineer (in today’s terms a surveyor) took him all over WA, OR, ID, BC, Alberta, Sask, with periods of unemployment in his field. That much I knew from my father’s stories. As it happened, he was working in Medicine Hat, Alberta, for the Canadian Pacific Railroad as a lineman, which meant he was out of work in his field. He signed the card in Walla Walla, Walla Walla Co. WA between Christmas and New Years, 1918, during a two week trip there. Both his and his wife’s families lived there. Interestingly, he gave his father-in-law’s name, instead of his own, as a person who would always know where he was. So I got a lot of new information from this card. The WW II draft registrations are also useful. This same grandfather was living in a nursing home. I can’t imagine why the government bothered with nursing home residents, even though it was the “old man’s registration.” Perhaps they were just being sticklers, as it was based on age, or in case some of these men were there for rehab and might later recover. Most of the form was filled out in a very different handwriting from that on his WW I form, so I took it to be that of an administrator or secretary. He signed with an “X,” and yet a different handwriting filled in his name, but with a spelling that was phonetic but very wrong. When I found this, my father had already died. I asked my mother if she could help explain. She told me my grandfather was in the nursing home because of a massive stroke, which left him paralyzed. This would explain his inability to sign his name. The handwriting that gave his name next to the “X” was probably that of an aide, who just made her best guess, and didn’t even look at the front of the card, where his name was spelled correctly. So I learned perhaps even more from the WW II card.

One thing I discovered in searching the WWI Draft Cards was that the information is reported on more than one page, and I assumed that the microfilm was organized with the front page of the Draft Card being represented first for each individual. Not so in West Virginia! My aunt’s grandfather was a coal miner and I printed out his draft card information to show her and she said the description was incorrect — he was not 6’2″ with brown eyes and red hair! He was about 5’7″ with blue eyes and brown hair. So I went back to the data in Ancestry.com and looked at the page BEFORE his card and that was the description for her grandfather down to a tee. If I had not had her to verify or a photo of him I could easily have been misled.