Today, as most of us here in the United States enter our kitchens to cook, prepare, or bake our contributions for Thanksgiving dinner, many of us will reach into our bookshelves and pull out the recipe for those tried-and-true dishes that our families request (or sometimes expect) us to bring to dinner. If your kitchen is anything like mine, these recipes are usually pretty easy to find – they’re the ones on the index cards that have batter and sauce splattered all over them, and in the cookbook with the broken binding that seems to automatically open to the same wrinkled page with ripped edges.

Today, as most of us here in the United States enter our kitchens to cook, prepare, or bake our contributions for Thanksgiving dinner, many of us will reach into our bookshelves and pull out the recipe for those tried-and-true dishes that our families request (or sometimes expect) us to bring to dinner. If your kitchen is anything like mine, these recipes are usually pretty easy to find – they’re the ones on the index cards that have batter and sauce splattered all over them, and in the cookbook with the broken binding that seems to automatically open to the same wrinkled page with ripped edges.

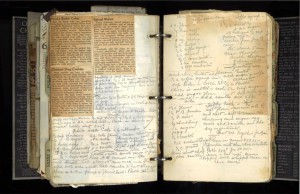

At the end of October, I got my hands on a collection of recipes that is not just a cookbook – it is an encyclopedia. I do not know who the previous owner(s) of this cookbook/encyclopedia was (or were), but I can tell that they really poured their heart and soul into the creation of this collection. As I was flipping through the pages (which is rather difficult since this binder is actually bursting at the seams), I found a recipe for just about any occasion. Stuffing, date bars, tomato preserves, liver fricassee: if you have a craving for it, you could probably find a recipe for it somewhere in the pages of this binder.

Although I thoroughly enjoyed seeing the decades-old clippings from newspapers and magazines taped, glued, and even pinned to the pages of the binder, my favorite finds were the handwritten recipes, or even better, the recipes that had handwritten corrections. These recipes jumped out to me because they reminded me so much of some of the cookbooks that my family has at home. For example, my favorite holding in my mom’s cookbook library, the Better Homes and Gardens Pies and Cakes book, has corrections and comments written in the margins by three generations of my family.

While cookbooks and recipe collections may not constitute primary resources for researching family history, I personally think that you can learn a lot about a family from these volumes: who did most of the meal preparation, favorite family foods, the family’s ethnic or geographical heritage, and even where they got their everyday information. If you look at the bookshelf in my mom’s kitchen, you’ll find a few of the essentials (Joy of Cooking, a few books by Julia Child), and a wide assortment of books on cookies, cakes, pies, and other desserts, many of which were inherited from her mom. Even though baked goods don’t stream constantly from home – much as I wish they would – it definitely shows that a sweet tooth is part of our genetic makeup.

In an attempt to learn more about the former owner(s) of the found recipe binder, I took a closer look at the types of recipes they took the time to include in their personal culinary encyclopedia. While I noticed that there was a rather thick section on canning techniques and recipes for preserves, applesauce, jams, and assorted pickled foods, I was incredibly saddened to see that the smallest section of the binder was dedicated to desserts. That, right there, tells me that there is no chance that I am related to whoever it was who put the collection together.

I think that my next step will be to sit down and really look closely at the newspaper clippings and pieces of scrap paper that fill the leaves of the binder. Hopefully, there will be a clue hidden somewhere in the pages that will lead me towards an answer. However, that will have to wait for another day. I guess I’ll have to return to my own index card with the molasses stain for the pumpkin bread recipe for this weekend’s big gathering. The only decision that remains is which note to follow about whether to add the raisins or not.

When my mom moved into assisted living at 96, a couple of years ago, she no longer needed her many cookbooks or her big recipe file. My younger sister, who cooks a whole lot more than I do, asked Mom for the recipe file. That Christmas, my sister pulled out from the recipe file 25 pages worth of the 3 x 5 cards that held the most family memories. She photocopied them, three per 8 1/2 by 11 page, complete with smudges, drops of ingredients, and Mom’s notations. Some of the recipes also were cut from the newspaper or the side of boxes. On facing pages, my sister “interpreted” each recipe, since in some case the original couldn’t really be read. For a front cover, on a sheet of Christmas stationery, she wrote a tribute to our mother and her cooking, and enclosed the whole thing in plastic covers. Each family member of whatever generation got a copy as a Christmas gift. The family doesn’t get together on Christmas day, but sometime the week after, that year at my brother and sister-in-law’s house. She suggested we each sign up for a dish from this little cook book, to recreate a meal from the family’s past. What fun that was, and what memories it sparked! The younger generation, each of whom cooked a dish too, learned a lot about their grandmother, and she was tickled to be eating what she used to make, without having to cook any of it. My offering was tomato aspic, a life-long favorite. My brother asked for part of the leftover aspic when it came time to pack it up–he hadn’t had any since leaving home. The entree was a Dungeness crab casserole, a regional favorite. This gift from my sister was a thoughtful use of Mom’s bulging old recipe file. And so was the meal my sister-in-law suggested we make from it.

Late in my mother’s life, when her eyesight was worsened by macular degeneration, I translated her favorite recipes to large type from the 3×5 cards. I thought I would have a coronary just reading them although I am know the result was delicious. I no longer have these recipes but recall the ingredients and instructions such as, cream 1 lb butter in a cup of heavy cream. A very clear signal of her formative years as a young bride during the deprivations of WWII. And her Thanksgiving dishes of celery and olives signal the family history and times. Recipes should be a considered more than food history but a reflection of the times and locale.

My mother kept a foot-long recipe file box containing recipes from friends and both sides of our family. The oldest recipe was “Sauce for Pudding”, written by my great-great-great grandmother, Hannah Haskell Poor (1823-1919). One Christmas about 30 years ago I took 36 of these recipes, wrote them on 3×5 cards, photocopied them, and inserted them into little photo albums. They were given to everyone in the immediate family and to the friends whose recipes were included. (I couldn’t leave out our neighbor, Barbara Sylvester’s “Whoopee Pies”!)

The vast majority of the recipes in Mom’s file were for baked goods and comfort food. No need to write down how to make beef stew, etc. I was surprised, though, to see that my great grandmother, Arlette Parsons Frellick (1866-1961), the daughter of a fisherman, wrote down a recipe for “Fish Chowder”. Then I realized that the recipe called for that new-fangled contraption called a pressure cooker. I’ll bet she could make pot chowder in her sleep.

The most intriguing recipe was for “Pork Cake” in which a pound of pork fat was softened with boiling water and used for the shortening. I asked my mother about it and learned that the cook, my great-great grandmother, Julia Black (1844-1926), was a cook in a lumber camp in the Adirondacks. This high-calorie cake was part of the lumberjacks’ breakfast.

Measurements and instructions were often approximate and visually evocative: shortening the size of an egg; alum the size of a walnut; jazz the meringue.

If I were to do it again I’d use images of the original cards, in the cook’s own handwriting, complete with splatters. When my mother died I took her copy of the booklet home with me, made dearer by her handwritten notes on the margins of some of the recipes and the date that she had made them.

I have the recipe box that was my grandmother’s. She will turn 104 on December 10th and is now living with my aunt. I would like to share her recipes in her own handwriting with my large extended family. I am wondering what the best way is to keep her writing, but take advantage of today’s paperless and indexable (I may have made up that word) technologies.