Typically, when researching family history, finding documents in which individuals state their relationship to each other is a source of excitement. These kinds of discoveries provide researchers with crucial information for genealogical research. However, during my time as a researcher here at NEHGS, I have come across some examples of direct statements of relationships that are not always what they appear to be. This insight specifically relates to colonial era documents, where relationships might be described differently than they are today.

Typically, when researching family history, finding documents in which individuals state their relationship to each other is a source of excitement. These kinds of discoveries provide researchers with crucial information for genealogical research. However, during my time as a researcher here at NEHGS, I have come across some examples of direct statements of relationships that are not always what they appear to be. This insight specifically relates to colonial era documents, where relationships might be described differently than they are today.

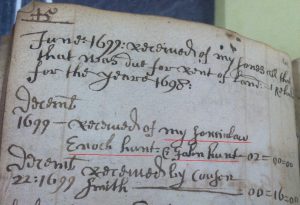

One example of this was a case I had that involved taking a look at one of our manuscript collections, The Account Book of James Blake, 1675–1754. My task for the case was to search this account book for any mention of the relatives of James Blake (1624–1700). I came across many notes relating to his sons, wife, and daughters, but what was interesting to me was that I also found a section that mentioned his three “sons-in-law,” John Hunt, Enoch Hunt, and Benjamin Hunt. It seemed improbable that James could have three sons-in-law with the same last name, especially since it appeared that he did not have three daughters.

In an effort to figure this out, I consulted one of our NEHGS databases, Torrey’s New England Marriages to 1700, to see if James Blake had a second marriage to anyone with the surname Hunt. It turns out this was indeed the case. Marriage records indicate that James Blake Sr. remarried after his first wife Elizabeth Clapp died in 1694. His second wife was Elizabeth Hunt. It would appear that John, Enoch, and Benjamin were her sons. Today we would refer to them as his “step-sons.” However, in the late seventeenth/early eighteenth century, the language used was somewhat different.

“In earlier times people often stated that an in-law connection existed when there was actually a step relationship. Any relationships created by legal means, including step relationships, were often identified simply as ‘in-law.'”

In her book, The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy, Val D. Greenwood dedicated a small section to the “Evolution of the Language” which helped me to sort this out. She explains this difference in language by stating that “In earlier times people often stated that an in-law connection existed when there was actually a step relationship. Any relationships created by legal means, including step relationships, were often identified simply as ‘in-law.'” It would make sense, then, that instead of calling Benjamin, Enoch, and John his sons or “step sons,” that he would call them “son-in-law’s.”

I have also come across many instances during this time period where what we would – in the present day – refer to as a “son-in-law” was simply referred to as a “son” – likewise with daughters who were of an in-law relationship. Greenwood also points out other cases of differences in language, including the fact that the titles Jr. and Sr. did not always mean father and son. It could simply refer to the fact that there were two people in a locality with the same name: one was Sr., the other Jr. I have of course come across instances of this where father and son were referred to as Jr. and Sr. as we do today. However, in some cases the Jr. and Sr. titles ceased when the Sr. passed away.

Another case where I found stated relationships to be different than suspected involved two “cousins” who were for some reason identified as siblings. In looking through probate records of a Coats family living in Newburyport, Massachusetts, I noticed discrepancies in a relationship I found identified there. According to Newburyport vital records, David Coats and Mehitable Thirston were married, had a child, and died in this town. Their daughter Elizabeth was also married in the town to a man named Thomas Greenleaf. In Mehitable’s will she stated her husband David had a nephew named Benjamin Coats. This nephew was given some money for his “advancement in life” in Mehitable’s will, since her husband David had died intestate the previous year.

Newburyport death and probate records indicated that Benjamin Coats was a mariner who died in the West Indies in 1793 at the young age of 22. He did not have a will, but I found a letter of administration for him which named Elizabeth Greenleaf administrator of his estate. What is odd about this case is that in these documents Elizabeth refers to Benjamin as her brother multiple times. However, in her will, Mehitable clearly indicates that Benjamin Coats was a nephew to her husband David, technically making Benjamin and Elizabeth cousins. It was unclear why Elizabeth referred to Benjamin as her brother, but perhaps she felt especially close to him.

These two examples serve to show that we cannot always take stated relationships at face value. We need to do our best to slip out of our modern day perspectives and find ways to view these historical documents through an alternate lens. Even if relationships appear to be clearly stated in the historical record, there may be instances where we may need to dig a little deeper to find additional supporting evidence when something doesn’t quite line up.

Sources:

- Account Book of James Blake, 1675–1754 (Mss C 2747), R. Stanton Avery Special Collections, New England Historic Genealogical Society.

- Torrey’s New England Marriages to 1700 <NEHGS database>.

- Val D. Greenwood, The Researchers Guide to American Genealogy, 3rd ed. (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 2000), 37–39.

- Barbara J. Evans, A to Zax: A Comprehensive Dictionary for Genealogists and Historians, 3rd ed. (Alexandria, Va.: Hearthside Press, 1995).

- Paul Drake, What Did They Mean by That? A Dictionary of Historical Terms for Genealogists (Bowie, Md.: Heritage Books, 1994).

- Vital Records of Newburyport, Massachusetts, in Massachusetts Vital Records to 1850 <NEHGS>.

- Benjamin Coats death, 1792, Newburyport, Massachusetts; Massachusetts Vital Records to 1850 <NEHGS>.

- Administration records, Essex County, Massachusetts: Probate Records, Old Series vols. 362–64, Books 62–64, 1792–1797, vol. 362, 506, 522 (NEHGS Microfilm).

- Ibid., vol. 363, 57–59, 63 (NEHGS Microfilm).

- David Coats household, 1790 U.S. census, Newburyport, Essex Co., Massachusetts <Ancestry>.

Note: Val D. Greenwood is a male.

I have been chasing for years a reference in a 1749 will of John Harvey to “my sister-in-law, Anna Scott, widow.”: His wife’s sister? I don’t think he was married. His brother’s widow, who has remarried? His sister’s husband’s sister? I had started looking for step-sisters, but what was Anna’s maiden name before she married? His mother’s daughter from his previous marriage, or his father’s? Or something else entirely? So this example perfectly resonates with me!

Likewise in the 1901 and 1911 Censuses of Ireland I have found several entries where a grandmother or grandfather was the head of the household but children who were clearly grandchildren are listed as nieces or nephews

That happened in Iowa in 1875! But by 1880 they were grandchildren. I was just starting my family search and had no idea why those census were so different.

Interesting post. But three sons in law with the same last name are not impossible. My great-great grandfather from Co Antrim had three siblings who all married three siblings from the neighboring farm. In my family’s case, it was two girls and a boy marrying two boys and a girl. Such practices were common among the Irish and Scots and perhaps other nationalities as well.

I have that exact same problem that I am trying to sort right now. Abigail Nabby Neaby Smith, niece of Gen. John Stark. She can’t be a daughter of his sisters. She isn’t a daughter of his sister’s children. I researched his wife’s Page family and have come to the conclusion she was Elizabeth Page’s “niece”. However, she was not the daughter of Elizabeth’s sibling. It gets so complicated I need the tree projected on the side of my barn and a laser pointer to explain. I have hunted high and low for a will for Gen. Stark and can’t find one. There has to be one somewhere! A will for Molly Elizabeth Page Stark would be heaven. I’m already 70 years old. That will needs to surface ASAP!

I like your comment “This will needs to surface soon.” Since many of us are “of a certain age”, we all feel that genealogy clock a-ticking. Good luck with your search, and may you have a successful conclusion to all your quests.

Not everyone left a will. Look at the land records of places he lived. You may find a “distribution of [his] estate listed there, which names the people (and many times the relationship) that have unraveled several of my sticklers.

John Stark very clearly came from New Hampshire, you might want to contact the State of New Hampshire records to obtain this information.

Well, that would explain a letter written to my 5th-great-grandfather (Lt. Samuel Treat of Boston) by Elias Parkman; Parkman signed the letter, “Your brother, Elias”. Turns out Parkman had married Samuel’s older sister Abigail Treat, making Parkman Samuel’s brother-in-law in today’s parlance.

And then there is also the practice of referring to fellow church members as “brother” or “sister”!

excellent article except one small thing: Val D Greenwood is a man.

I have encountered a similar situation in my mother’s earliest American ancestor, Nicholas Ide of Rehoboth, MA, who is referred to in the 1647 will of Thomas Bliss of Rehoboth as “my sonninlaw”. It leaves two options: the first and usual interpretation is that he married the daughter of Thomas Bliss and indeed she is often identified, seemingly without strong evidence, by her supposed maiden name, Martha Bliss. But there is a long tradition that Nicholas was the son of a widow Ide who married Thomas Bliss, himself a widower, and it is by reason of adoption that Nicholas is identified as Bliss’s son-in-law . As far as I know neither option has stronger evidence behind it than the other. And, indeed, it is possible that both options are true.

I have worked on this Ide issue myself. I think that the Thomas Bliss reference to Nicholas as his son in law meant that he was a stepson for several reasons. Firstly in his will Thomas twice says he has four children, but other than Nicholas he only names one son and two daughters. He also identifies the husbands of the two daughters as sons in law, but identifies which of his daughters they are married to. Most telling, is that a year later Nicholas sues the estate for a child’s portion without naming his wife, even though she was very much alive–seems unlikely if the Thomas Bliss child was his wife.

This particular issue has been in debate for a long time.

I especially appreciate this post. You succinctly present a situation and unwrap the details clearly so that the important lesson is not lost. I am thinking happily of this newly gained useful knowledge I can apply to my own research. Thank you!

Regarding Benjamin Coats, “nephew” of David Coats but “brother” of David’s daughter: I was immediately reminded of the scene in Great Expectations where Pip’s brother-in-law is asked whether Pip is really his “nevy.” Nephew, or nevy, could be a euphemism for an illegitimate child. Perhaps Benjamin really was Elizabeth’s brother.

Rebecca, could you possibly be related to any Page family a really long time ago? I have a boatload of Smiths. None seem to be related to each other. I was hoping.

Your reference to Benjamin Coats really caught my eye! Is this part of your own family or one you have researched for someone else? If it is your family, we may be cousins of some degree! One of my great-grandmothers was Amelia Coats and I have run into a stumbling block, (probably from my own carelessness in my early genealogy work) about her parentage.

Note that in France the “step” and “in-law” issue is still a problem as the designation is identical.

stepson and son-in-law = beau-fils

stepmother and mother-in-law = belle-mère

and so on.

I have noticed that in most obituaries from before WWII, the obituary does not distinguish between the surviving children and step-children. Without knowing the family already, this would not be clear. Also, children who predeceased their parents were seldom if ever mentioned, even if they died as adults and left children of their own. Again this could be very misleading if you did not already know the family already. Nevertheless, old obituaries can be fantastic sources of information.