I grew up with an understanding that I had German and Irish roots. My paternal grandfather would often pull out a few German phrases he learned from his grandparents. On my mother’s side my cousins and I all took great pride in being “Kiley girls.” While these identities were strong in my upbringing, it wasn’t until I was older that I realized my most recent immigrant ancestor was not German or Irish, but Czech – an identity that was not impressed upon me at all.

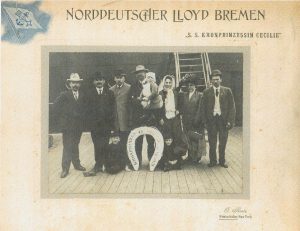

My father’s maternal grandfather, Joseph Kler, was born in Chicago in 1903 shortly after his family’s immigration. They returned to the old country for about three years while Joseph was a young child. A photograph of their return trip to the United States when Joseph was an adolescent hangs proudly in our living room.

Joseph had a passion for history – particularly American history.

Even though he had lived in what was at the time the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was old enough to remember his return voyage to settle permanently in the United States, Joseph was extremely proud of being American. He seemingly rejected any remnants of the old county. In a book of family papers compiled by my grandmother’s sister, Marjorie, she noted that her father anglicized the surname from Klir to Kler (as seen in official documents). She lamented the fact that she did not learn Czech as many of her cousins had. According to Marjorie, her father always said that they were Bohemian Czech, but the family story in the old country was not passed forward.

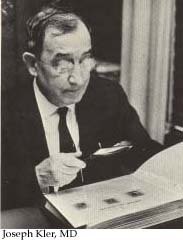

Once in the states permanently, Joseph was raised on a Wisconsin farm and then went to medical school. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical College in 1925 and served as a flight physician in the Navy. He was an ophthalmologist who practiced in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and was the chief of ophthalmology and otolaryngology at St. Peter’s Medical Center for thirty years. But for all his medical training, he had a passion for history – particularly American history.

Once in the states permanently, Joseph was raised on a Wisconsin farm and then went to medical school. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical College in 1925 and served as a flight physician in the Navy. He was an ophthalmologist who practiced in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and was the chief of ophthalmology and otolaryngology at St. Peter’s Medical Center for thirty years. But for all his medical training, he had a passion for history – particularly American history.

Joseph became a collector of pieces with historical significance. He also was a noted collector of historic pewter, Meissen china, and silver. His American pewter collection was so extensive that he donated the best pieces on permanent loan to the Smithsonian Institution. The remainder was sold by Christie’s Auction House. His Meissen china and silver appeared in the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton. He was also an avid collector of stamps with a medical theme, donating his rather large collection to the Cardinal Spellman Philatelic Museum at Regis College in Weston, Massachusetts – a museum of which he was a founder.

Joseph was also an architectural preservationist, organizing and leading the East Jersey Olde Towne project which saved historic structures from demolition and moved them to one site to recreate a colonial village. The entire project began with his effort to save the Indian Queen Tavern in New Brunswick, which quickly grew to a larger preservation effort. In an article on the creation of the village, Joseph noted, “We are interested in preserving a visual conception of our past so that young people can conjure up a picture of the way it was in Colonial times.”[1]

Joseph was also an architectural preservationist, organizing and leading the East Jersey Olde Towne project which saved historic structures from demolition and moved them to one site to recreate a colonial village. The entire project began with his effort to save the Indian Queen Tavern in New Brunswick, which quickly grew to a larger preservation effort. In an article on the creation of the village, Joseph noted, “We are interested in preserving a visual conception of our past so that young people can conjure up a picture of the way it was in Colonial times.”[1]

He also tried his own hand at writing history, composing a history of the Bound Brook Presbyterian Church.[2] Joseph’s family had been Catholic prior to their immigration, but his conversion to Presbyterianism and a marriage to a woman with deep colonial roots solidified his Americanism.

He spent his lifetime chasing the American dream and preserving a history which was not directly his own.

Joseph spent his lifetime chasing the American dream and preserving a history which was not directly his own, as none of his ancestors ever lived in colonial America. Evidence of the importance of American history in his life can be found in his obituary, which focuses more on his collections and preservation work than his career in medicine.[3]

From the perspective of his great-granddaughter, Joseph’s efforts were a part of his desire to truly be American and to pass on that pride of country to his children and their children. He saw himself as fully American. The sense of a Czech identity never reached me, though I know from learning more about Joseph Kler that his love of American history was passed to his daughter (my grandmother), to her son (my father), and then to me. I hope to carry forward Joseph’s sense of civic duty in the preservation of American history and by sharing his pride in being American.

Notes

[1] Muriel Freeman, “East Jersey Group Re-creating Village,” New York Times (November 4, 1973), 127.

[2] Joseph H. Kler, MD, God’s Happy Cluster: 1688-1973, History of the Bound Brook Presbyterian Church, (n.p., 1963).

[3] “Joseph H. Kler, 80, Physician and Preservationist in Jersey,” New York Times, (November 25, 1983), D00021.

My grandparents also came from the Austro-Hungarian Empire and called themselves German. Twice the Austro- Hungarian Empire offered free land to immigrants to settle areas of the empire. I understand the areas were often invaded by the Turks and they wanted a buffer zone. There was very little intermarriage between the native residents and the Germans. Therefore they kept there German language and customs. My grandparents all there life felt they were German, not Hungarian. The town they lived in was predominately peopled by other Germans. Now it is part of Romania.

My great-grandparents also were Transylvanian Saxons from Austria-Hungary. They spoke German and followed German customs. They told their children and grandchildren they were German. They never

Hi Meaghan,

Great post! It reminded me of my great-grandfather who left Bohemia in the late 1870’s with his wife and family. He made every effort to forget the old country, leaving my generation to reconstruct his early history, and indeed his life experiences. As a boy, I wondered why he uprooted his family and came to America. The short answer is that relaxed governmental restrictions and mechanized transport made it possible to leave. He ran from an oppressive government, whose business was transacted in a language other than his own, and a Church which branded him forever illegitimate despite his parents later marriage. The harder question is, why did anyone stay in a place where the legacy of serfdom was strong.

Once in America he became a Presbyterian (Presbyterians established mission churches in Chicago, which attracted many Czechs.) after a dispute with his parish priest.

I have enjoyed digging out his story from a few tales of his life in America and, surprisingly, some records from his early life.

All fascinating! While at UPenn in grad school, the emminent historian Otokar Odlozolik %spellin uncertain now- taugh German history. He had served in Bulgaria in WWI with the army of the Austo-Hungarian Empire. He arrived in Vienna the day the Empire fell, and his description of the chaos and getting back to what was in 1963 Czechoslovakia was fascinating. To the point of this article, however, I am often impressed. Y how much more fervent new Americans are than those of us born here.

Hi Meaghan,

Loved your post as it connects to my NJ ancestors in a couple of ways, plus I grew up in

Middlesex and Bound Brook. My 4th ggrandmother was Sarah Runyon so I have a connection

to the Runyon house in the East Jersey Olde Towne Project that Joseph did so much to

preserve. Also, my 2nd ggrandfather, Peter Hodge Smith (1838-1924) was a longtime

member of the Presbyterian Church in Bound Brook. While he and Joseph wouldn’t have

met I’m certain he would have been very pleased with Joseph’s writing of the church’s history.

Thank you for writing about Joseph and all that he accomplished and providing me an

interesting connection to your story!

Judith

A perfect post for July 4! Thank you.

Hi Meaghan, thanks so much for writing about your great grandfather. Reading your post allowed me to take a walk down memory lane as he was my ophthalmologist from the time I was in grammar school until he retired. He even fitted me for my first pair of hard contact lenses when I was a senior in high school! I was aware of his key role in East Jersey Olde Towne and have visited a number of times over the years. Thanks for the stroll!