On Friday, I wrote about some of the most widely-read Vita Brevis posts of 2017. To mark the beginning of the next year, here are six more popular posts showcasing the range of subjects covered in a blog that publishes about 250 posts a year. (In fact, Vita Brevis marks its fourth birthday on January 10, and the blog’s one-thousandth post was published in November.)

On Friday, I wrote about some of the most widely-read Vita Brevis posts of 2017. To mark the beginning of the next year, here are six more popular posts showcasing the range of subjects covered in a blog that publishes about 250 posts a year. (In fact, Vita Brevis marks its fourth birthday on January 10, and the blog’s one-thousandth post was published in November.)

In July, Michelle Doherty laid out a genealogical case using “Circumstantial evidence”:

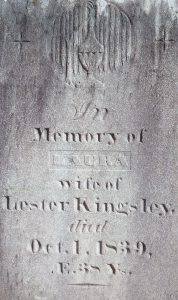

All I knew was that Benajah married a Laura Smith. I searched for a death record for Laura, wife of Benajah Lester Kingsley, and found death and cemetery records for her. These indicated that Laura died in 1839 at the age of 38, giving her a year of birth of 1801. Next, I looked at the NEHGS database, Massachusetts: Vital Records, 1620-1850. I searched for Laura Smith, born in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, around the year 1801. Two results came up: one Laura Smith born in Becket in 1806 and another born in a town called Sandisfield, about 30 miles south of Becket. Two very plausible options for the wife of Benajah, one born in the same town as him but with a different date of birth, and another with the right date of birth but [a birthplace] somewhat far away from Benajah.

All I knew was that Benajah married a Laura Smith. I searched for a death record for Laura, wife of Benajah Lester Kingsley, and found death and cemetery records for her. These indicated that Laura died in 1839 at the age of 38, giving her a year of birth of 1801. Next, I looked at the NEHGS database, Massachusetts: Vital Records, 1620-1850. I searched for Laura Smith, born in Berkshire County, Massachusetts, around the year 1801. Two results came up: one Laura Smith born in Becket in 1806 and another born in a town called Sandisfield, about 30 miles south of Becket. Two very plausible options for the wife of Benajah, one born in the same town as him but with a different date of birth, and another with the right date of birth but [a birthplace] somewhat far away from Benajah.

Jeff Record has written several posts about his grandmother and her adoption by his great-grandmother. In “A knock at the door,” he describes a fateful encounter:

Jeff Record has written several posts about his grandmother and her adoption by his great-grandmother. In “A knock at the door,” he describes a fateful encounter:

She was not pleased to see me – this paternal first cousin of my (biological) great-grandmother, Opal Young. Her name was Grace, and we had arranged our meeting through the mails, never having spoken to each other by telephone. Before, as I had stood on her stoop waiting for her to answer my knock, it was hard for me to believe that I would be meeting with a blood relative of my grandmother’s – one outside the small circle of my grandmother’s own descendants. I wondered how she might appear to me (part of me thought surely on a broomstick?) and I wondered what of “her family” she might recognize in me, too.

In some ways I am not sure why Grace agreed to see me at all. She was, after all, a 91-year-old spinster living alone in the hills above Glendale, California. While I had done my best to answer her many questions in advance, the prospect of meeting a strange relation at the door that day must have both daunted and intrigued her. After our initial written exchanges, I had sent Grace a copy of Opal’s letters to my grandmother. I wanted her to have these as proof of life – that I was indeed her “childless” cousin’s great-grandson.

In September, Pamela Athearn Filbert wrote about her own serendipitous encounter with a stranger. She paraphrases the sort of letter that many of us would like to receive (or perhaps to write):

In September, Pamela Athearn Filbert wrote about her own serendipitous encounter with a stranger. She paraphrases the sort of letter that many of us would like to receive (or perhaps to write):

“Hello. Based on your family tree, I have a photo album that might be of interest to you. It was rescued from a dumpster, and I’ve had it in excess of 25 years without doing anything with it. My genealogy group has a show-and-tell meeting coming up on July 11, and as I’ve been a member for so long, I couldn’t think of anything I haven’t already shown. Then I thought of this album, and thought maybe I could finally do something with it, so have been researching names in it.

“There are about 42 pages with photos, 95% of which have everyone’s names on the back. There are several photos of groups of people at family gatherings. These are mostly Abe Whitaker [my great-great-grandfather, whose likeness I had never seen!] and his daughters Josie and Mertie. I would like to know if this is something you would want. Please let me know if you get this message even if you are not interested.”

In October, I described the events surrounding a talk I had been scheduled to give on my new book. The talk was cancelled, for reasons that remain unclear; at least one bystander commented that my subject matter was sure to be controversial:

In October, I described the events surrounding a talk I had been scheduled to give on my new book. The talk was cancelled, for reasons that remain unclear; at least one bystander commented that my subject matter was sure to be controversial:

Years ago, when I was working on my first full-scale genealogy, one of my cousins expressed strong reservations about her entry in the book. She had been married (and divorced) four times, and her first reaction was to push back on what I had written down. We talked on the phone about it, though, and at the end of the call she said, ruefully, “Well, I did it – I married them – and I’ve got no one to blame but myself.” I think (and hope) she realized that there was nothing malicious in my presentation – that I was simply presenting to future readers the fullest possible account of this aspect of her life, as I was doing for her siblings and all our other cousins.

Getting that part right – and not the scandalous nature of this or that person’s biography – is the measure of the book’s success. The lecture is transitory, but the emotions around its cancellation are telling.

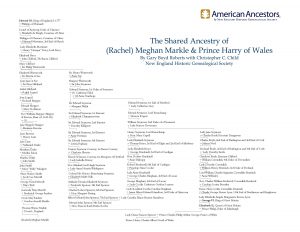

A royal engagement provided the pretext for Christopher C. Child’s examination of “The Wentworth connection” between Meghan Markle and Prince Harry of Wales:

A royal engagement provided the pretext for Christopher C. Child’s examination of “The Wentworth connection” between Meghan Markle and Prince Harry of Wales:

As Gary Boyd Roberts announced yesterday, Meghan Markle has a distant kinship to Prince Harry through their shared descent from Sir Philip Wentworth (died 1464) and his wife Mary Clifford. While Gary continues to work on much of Meghan’s American ancestry, especially her forebears in colonial New England, I’ve composed the chart from his notes. This outlines the three closest kinships between Meghan and Harry that have so far been identified – two through Harry’s mother and one through his father. As Gary has noted, there are hundreds of other ways they would be distantly related.

I’ve also been working on Meghan Markle’s American ancestors, so stay tuned!

In December, and in preparation for the 400th anniversary of European settlement in Plymouth, Sarah Dery began a new series on texts associated with Mayflower passengers William Bradford and Edward Winslow in “Trouble with Speedwell”:

In December, and in preparation for the 400th anniversary of European settlement in Plymouth, Sarah Dery began a new series on texts associated with Mayflower passengers William Bradford and Edward Winslow in “Trouble with Speedwell”:

We know the story of Mayflower carrying 102 brave souls to the New World, but do you know about Speedwell? This vessel, captained by a man named Reynolds, was a ship that was to accompany Mayflower on its journey. In the paragraph below, taken from Bradford’s book [Of Plymouth Plantation], the Governor describes the ‘lesser ship’ and those who had to turn back.

Being thus put to sea, they had not gone far but, the master of the lesser ship, complained that he found his ship so leaky as he durst not put further to sea till she was mended. So the master of the bigger ship (called Mr. Jones) being consulted with, they both resolved to put into Dartmouth and have her there searched and mended, which accordingly was done, to their great charge and loss of time and a fair wind. She was here thoroughly searched from stem to stem, some leaks were found and mended, and now it was conceived by the workmen and all, that she was sufficient, and they might proceed without either fear or danger…