As my grandfather[1] prepared to graduate from college, he was ready to cast off academics and explore the world instead of following his father into a law career. Generations of his sea-faring family had literally charted the way, and the possibilities beckoned to him every time he gazed out the windows of his home towards San Francisco’s (then bridgeless) Golden Gate.

He signed on as an ordinary seaman aboard the Hollywood, a World War I-era freighter in McCormick Steamship Company’s Pacific-Argentine-Brazil Line, and his salary was $45 a month plus room and board … such as it was. After completing his cruise around Cape Horn and back through the Panama Canal, he worked for McCormick in several capacities over the next decade, including sailor recruitment and passenger services.

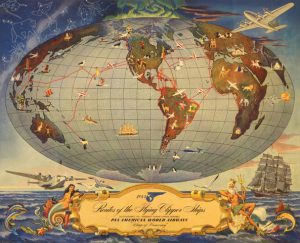

By 1940 he was ready for something new, and was hired by Pan American Airways as a manager for their Pacific flying boat service. He flew to Honolulu for training in early October before heading to Canton Island (named for a New Bedford whaler) to apprentice under their station manager.

In addition to swimming and fishing – the usual entertainments found on a remote island in the middle of the Pacific – my grandfather found himself dining nightly with Noël Coward[2] during the latter’s escape from civilization in February 1941. The station manager felt that only he, his wife, and my grandfather were suitable dining companions, though Mr. Coward graciously sang and played the piano afterwards in the employees’ recreation hall, which was thoroughly appreciated by everyone in that isolated outpost.

A few weeks after Mr. Coward’s departure, my grandfather headed back to San Francisco to escort his wife and children to Noumea, New Caledonia, where he was to become the new station manager. This was the last stop between Honolulu and New Zealand. My seven-year-old father[3] and five-year-old aunt[4] soon found themselves attending a school in which everyone spoke only French, and living in a house provided by Pan Am near the top of Mont Coffyn (also spelled Mt. Coffin) – without a doubt named by and/or for some distant relative of both my grandparents during whaling’s heyday.

Their idyllic life on the island was cut short the morning of December 8, 1941,[5] soon after my grandfather finished overseeing the takeoff of Pacific Clipper NC 18602. While en route to New Zealand, the crew learned of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and subsequently spent several days awaiting further orders after dropping off their passengers.

In the meantime, my family learned of the attack through their next-door neighbors, who had heard it on “Radio Saint Sanatie” (this turned out to be Radio Cincinnati, which had a very strong signal). The whole town immediately went into brownout, and a few days later my grandfather received a cryptic message about fuel supplies from the Australian Air Force.

[Everyone] needed to report to the plane immediately, with one bag apiece weighing no more than 40 pounds.

Finally, early on December 17, my grandfather received a call alerting him that the clipper was returning. He quickly took a launch to the island where the seaplane base was located. When the flying boat arrived, the captain said that his orders were to evacuate the American Pan Am employees and dependents; everyone needed to report to the plane immediately, with one bag apiece weighing no more than 40 pounds.

Since none of the other employees had phones at home, my grandfather called his wife[6] to solicit her help: “Get in that car and go like Paul Revere.” She was in such a hurry that she didn’t even stop to put on undergarments before heading off with the driver to alert everyone!

Despite the heat and hurried conditions, everyone was appropriately attired according to the standards of the day by the time they boarded the plane. My aunt recalls wearing a wool suit, and how upset she was when the draught of the plane’s propellers pulled her cap off and tossed it in the sea.

The heavily loaded plane finally made it off the water, and dropped its bewildered passengers in Gladstone, Australia, late in the day. Then, in order to keep the plane from being captured by enemy forces, the crew flew the plane – with no charts, no flight plan, and no radio contact – westward over Asia and Africa, then over the Atlantic to Brazil, and finally north to New York City. It was the first circumnavigation of the globe by a commercial plane.

My aunt celebrated her 80th birthday by attending Pan Am’s 2016 reunion in Ireland; it included a trip to the Foynes Flying Boat Museum where a replica of the Yankee Clipper – a twin to the Pacific Clipper – can be toured. She even got a special surprise by being featured on Irish television’s RTÉ program “Nationwide,” which can be viewed here; her segment starts at 7:15. Her role in transportation history may not be quite so impressive as being the last survivor of the Titanic … but she’ll take it.

Notes

[1] Folger Athearn (1906–1992).

[2] (Sir) Noël Coward (1899–1973) was a British playwright, actor, and composer/lyricist, who enjoyed spectacular success during the second quarter of the 20th century.

[3] Folger “Jerry” Athearn, Jr. (1934–2000).

[4] Marion “Merry” (Athearn) (Herb) Barton (b. 1936).

[5] New Caledonia lies across the International Date Line from Hawaii.

[6] Marion Agnes (Whitaker) Athearn (1906–1989).

What an interesting family story. Did they stay in Australia long and where did they go next? Did your grandfather continue with Pan Am?

Maybe I’ll write a Part II. If so, here are some spoilers: 1) no; 2) Florida by way of California; 3) yes. And just a couple of weeks ago a woman contacted me through ancestry.com to say that she was startled to find Folger and Marion Athearn on a tree containing one of her ancestors, since she remembered them well when they were living in Lima, Peru. Her father and my grandfather were both working for Braniff at that time. Small world! (Literally, in this case.)

Lucky girl. What a great, adventurous family you have. Right in the middle of so much history. Thanks for sharing!

Yes, I’m lucky to have some cool stories in my past, and I know this one because my grandfather recorded some memories in 1976 for his grandchildren. My aunt did the same for her grandchildren when the oldest two graduated from college, and receiving a copy is what helped launch my interest in genealogy. David Allen Lambert admonishes those of us who seek out our ancestors’ stories to do OUR descendants a favor and not neglect to record our own stories, too!