Much has happened with the Society’s Civil War digitization project, funded by the Cabot Family Charitable Trust, since Abbey Schultz’s last article on quality assurance. Our vendor completed all scans in June 2016, ending the imaging portion of the project. The focus then shifted to preparing the images to be uploaded into CONTENTdm software so they can be displayed on our Digital Collections website.

Much has happened with the Society’s Civil War digitization project, funded by the Cabot Family Charitable Trust, since Abbey Schultz’s last article on quality assurance. Our vendor completed all scans in June 2016, ending the imaging portion of the project. The focus then shifted to preparing the images to be uploaded into CONTENTdm software so they can be displayed on our Digital Collections website.

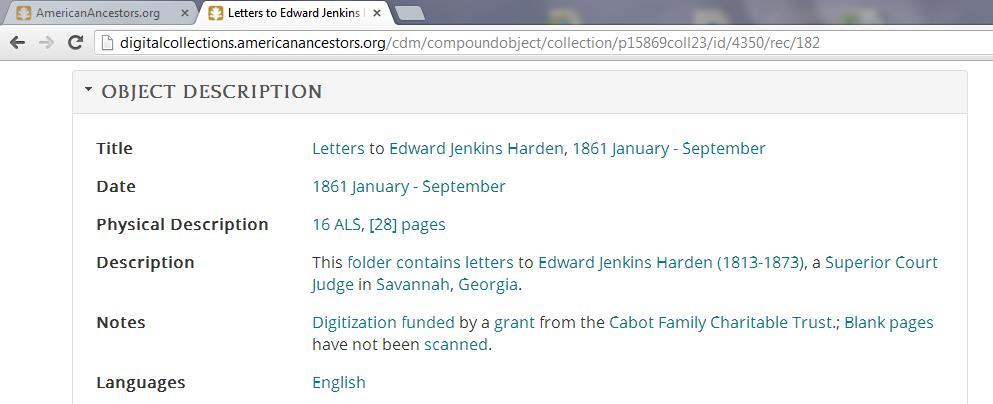

A major component of this preparation focused on the gathering of metadata that would be uploaded with the images. Metadata, often defined as data about data, is simply the information used to describe each image. A typical example of metadata familiar to many people would be a library catalog record. The catalog record has data describing an item including its author(s), title, publisher, subject matter, physical description, acquisition date and method, and location.

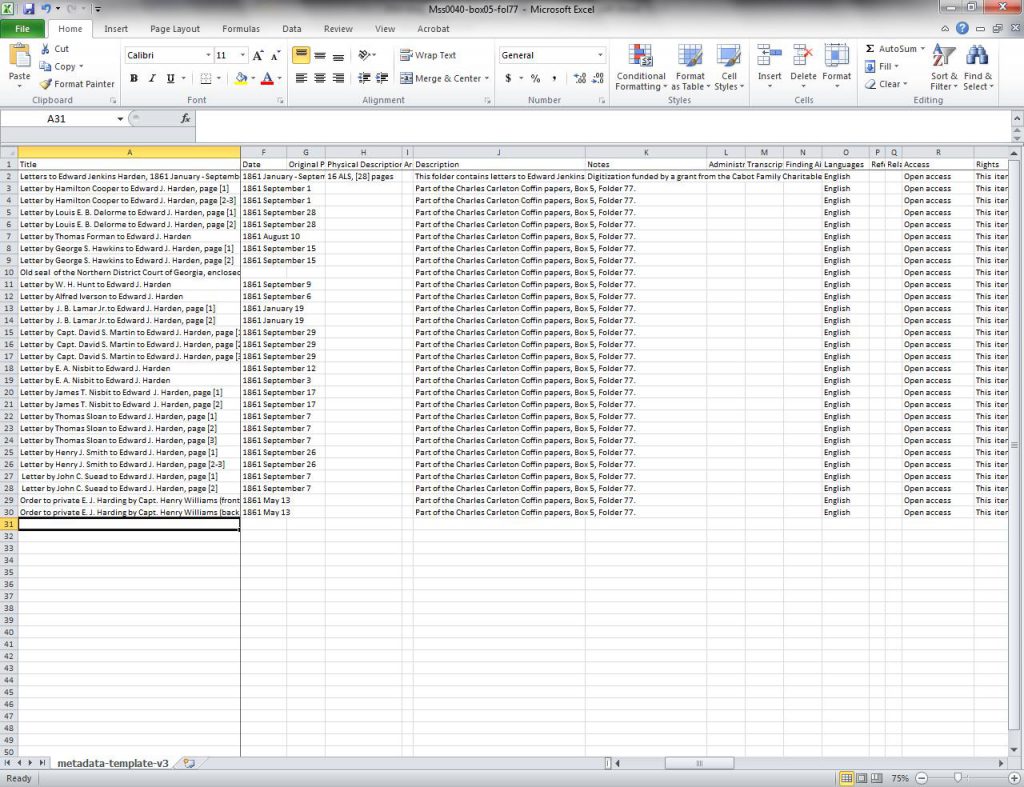

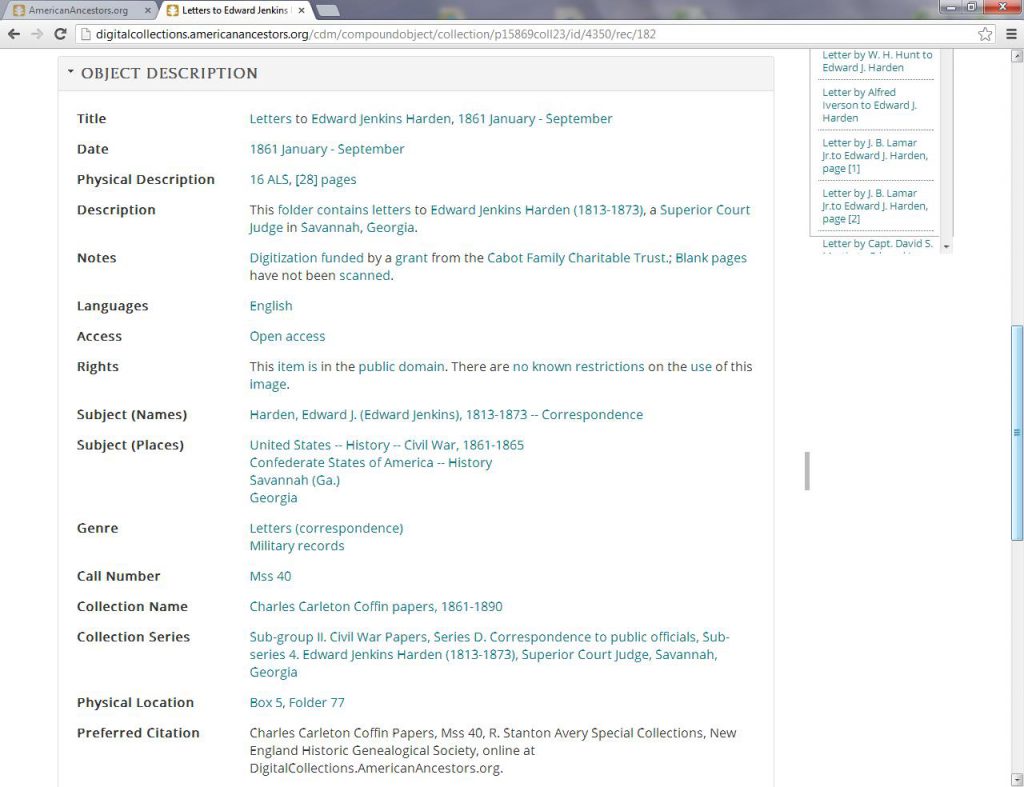

NEHGS Special Collections documents some twenty-six data elements for each digital image (thus there is a column heading for each in the spreadsheet) including title, creator, date, description, language, access, rights, subjects, call number, collection name, physical location, preferred citation, and repository name. A spreadsheet is used to facilitate assembling the metadata because of its copy, paste, fill down, and other useful editing features.

The first row of the spreadsheet contains the column headings, the second row has data for the entire object (archival folder, account book, diary, photo album, etc.), and the subsequent rows have the data describing each individual image file.

The digital image files are batch converted to JPEG format for easy loading in web browsers. When fully populated with data, the spreadsheet is converted to a tab-delimited text file since this is the file format required by CONTENTdm software for imports. When all images and metadata are ready, the files are imported into CONTENTdm.

The data transfer does require precision and attention to detail. The upload of the image files and metadata will stop at the first error and the entire upload will fail because of a typo in a file name, an extra tab, or incorrectly formatted date. Once the upload is successful, the Curator of Digital Collections needs to approve the new digital items and controlled vocabulary. The images are still not visible by the public until the entire collection is indexed – this can take several minutes to an hour.

The following Civil War collections have been successfully uploaded and are now available to the public: Civil War Papers of Captain John T. Burgess, 1860-1914 (Mss 1088); Chapman Family Correspondence, 1861-1865 (Mss 1070); Charles Carleton Coffin Papers, 1861-1890 (Mss 40); and the Howard Family Papers, 1860-1910 (Mss 459). Sally Benny, Curator of Digital Collections, and a volunteer are finishing uploading the final images and metadata for the last collection, Civil War Papers of Captain Leander Gage King, 1861-1933 (Mss 1073). We are very grateful to the Cabot Family Charitable Trust for its generous support of this project!

What a surprise to see listings of letters concerning my gr-gr-gr-grandfather, Judge Edward Jenkins Harden, in the NEHGS files!

I have to offer my sincere appreciation for what you do. Your work is truly the “silent hero” behind all of our research.

Bravo!

Who knew!!! Your article has inspired me to do the same with my own family history collections, which should make it handier for the local historical society to deal with after I am gone. Thanks for sharing!!!!!

Thank you for the inside look at how professionals compile and transfer metadata using modern software. Years ago I assembled metadata for different kinds of projects (mostly scientific), but then it was a cumbersome process, and the end product not so usable unless one was familiar with the freakishly obtuse search terms of the time. I have always indexed my collection of notes, images, etc– at least once I get them organized, which is another topic. But this article gives me some ideas for doing it in a more professional manner. even if all I get done is the spreadsheet part. I developed a resistance to data entry after all those projects, but have to admit that genealogy is a lot more interesting than painstakingly entering data with numbers and digital points. One thing I have learned about doing this kind of thing is that it gives me a much better overview of what I’ve got and how it fits together, so it is not only a tool for organizing, it can be a valuable tool for analysis, too.