I frequently contribute to a column on The Root online magazine, where I respond with Henry Louis Gates Jr. to genealogical questions from the readers. Often the questions involve trying to trace families back to the slavery period, which is a daunting and difficult task. Not only are records hard to come by, but the work can be an emotional rollercoaster.

It is mixed with the delight of finding an ancestor listed by name in a probate record, quickly followed by the realization that they are there because they were property. It can be hard to face the realities of the past when seeing children listed with monetary values next to their names, but also rewarding to know you have pieced a family together with the record.

Unfortunately, these are the types of records you hope for when conducting slave research. You have to dig deep into a slave owner’s probate and account files in the hopes that people are mentioned by name as a part of their property. The type of records that can hide there are sometimes surprising. The article I worked on recently, “What’s the Story of a Portrait of My Slave Ancestor?,” found me browsing page by page through Richard Keith Call’s probate file. Call was a former Governor of Florida and he owned two plantations and hundreds of slaves. He died in 1862, prior to Emancipation, and his probate file includes lists of his slaves from both plantations. I was acquainted with his probate from a previous column, also for The Root, but discovered something new this time.

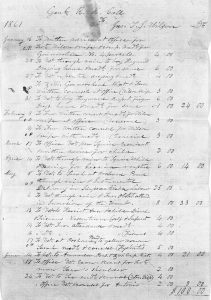

[It] is very clear that these are entries for medical services for Call’s slaves.

Digging deeper into the probate file than I had done before, I found a number of pages of account records for the local doctor, Dr. John T.J. Wilson, for the years immediately prior to and following Richard Keith Call’s death. These could have been easy to overlook, but if you read the entries and compare them to the list of slaves in the probate, it is very clear that these are entries for medical services for Call’s slaves. The entries include a range of services from the care of wounds and conditions to the prenatal care and delivery of a number of babies.

Most of the entries include the name of the individual or individuals being treated, which can provide an intimate look at the lives of those enslaved on Call’s plantations. In the recent article for The Root, we were searching for a young man named Hanover whose brother, Hayward, was living with him and his wife, Bettie, in 1880. They all would have been children when Richard Keith Call died.

This account record notes the dressing of Hayward’s hand…

This account record notes the dressing of Hayward’s hand and an amputation of his finger a few days later. A later entry in the probate file notes that Hayward was not well, suggesting that maybe he was living with his brother in 1880 because he could not support himself. These are details we would never know without this record.

There are also entries that reveal much about the conditions on the plantation, including a number of charges for consultations and medication for the treatment of venereal disease. There were also recurrent visits for the abstraction of teeth and the use of medication for rheumatic conditions that speak to the toll a life in slavery took on the body. This record reveals a part of these ancestors’ experiences that is not typically documented, making this a rare and exciting find even though it is also records a heartbreaking reality.

Meaghan,

My brother located the will from about 1815 for George Waggoner, the brother of Isaac Waggoner, one of our ancestors. It didn’t include all the details about the brother’s slaves that you found for Call’s slaves, but the details it did include were very interesting, and poignant. We have a family history book written in the 1920s for this family, including a bit about their father. The brothers were born in South Carolina. Isaac disapproved of slavery, so between the 1790 and 1800 censuses he moved his family to North Carolina. Of course slavery existed there too, but according to the censuses, he never owned any. George moved to Georgia, bought a large plantation, and became a slave owner. The book, based on oral history, gives the impression that the brothers were not close. However, the will shows that Isaac was one of three executors, attended the auction of George’s property, and bought a few items. But the most striking thing was what the will said about the George’s slaves. He freed one woman outright. If I were tracing my ancestry back to this slave owner, and this slave, I’d wonder if he were the father of any of her children. His other half-dozen slaves were all to be freed outright at the age of 35. However, in the meantime, they were to be sold at the auction, individually. That shocked me, because I would assume at least some of them were family. Once sold, how was anybody else to know when they reached 35 and should be freed? And how were they to find each other? The other thing that shocked me was that, while the family book indicated George was a rich man, the only thing of value he owned was his slaves. The prices for them ranged from under $100 for a very young girl to $400 for a man in his 20s, who presumably was prime working age. At the auction, all were sold to different people. The next most valuable items were livestock, a cow and a pair of oxen. Everything else was odds and ends, selling for a pittance. The will specified how the proceeds from the auction were to be divided, going to his children, grandchildren, and Isaac. I presume that making sure there was cash to “provide for” his descendants was the reason for selling his slaves, while also providing for their freedom years down the line. If I were one of those slaves, being sold and having to wait for my freedom, I wouldn’t be very happy. How often have you come across this situation in your research?

Doris