Twenty-first century genealogists enthusiastically debate the relative merits of different types of DNA testing: autosomal (atDNA), Y chromosome (Y-DNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). But how often do you hear discussions about a medical family history or medical pedigrees? And yet knowing one’s medical family history may the best predictor of your risk or a relative’s risk of developing specific but also preventable or treatable diseases.

The predisposition to many illnesses may rest in our genes. Examples include cancer (up to 33% of diagnoses associated with our genetic heritage[1]), functional alcoholism (60% genetic[2]), and asthma (50% genetic[3]). So paying attention to our ancestors’ medical history makes sense.

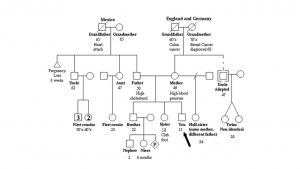

A medical genogram is a simple and effective way to capture and display your medical pedigree (see Figure 1). Begin by making a list of all your family members, going back to at least your grandparents, if not farther. Then interview as many relatives as possible. (Sound familiar? All good genealogists interview their families!) Next to each person’s name document their age or date of birth, date of death, and key medical conditions. Your list of conditions may include: cancer, heart disease, diabetes, asthma, mental illness, high blood pressure, stroke, kidney disease, birth defects (e.g. spina bifida, cleft lip, heart defect), developmental delays or disorders (e.g. issues with cognitive functioning, autism spectrum), vision or hearing loss at an early age, or known genetic conditions, such as cystic fibrosis or sickle cell. The date of onset of each condition should be included, when known.

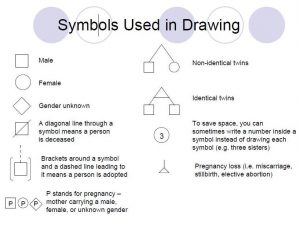

Now you are ready to draw (see Figure 2). On a medical genogram males are displayed by a square and women by a circle. Begin by placing yourself towards the bottom of the chart and call attention to yourself with an arrow. Add your siblings and their key medical conditions – older siblings to the left and younger siblings to the right, with vertical lines upward from the gender symbol. Join your siblings by a horizontal line. Next add your parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. Detailed instructions for the drawing process may be found at the National Human Genome Research Institute.[4]

As genealogists we have a responsibility to preserve the past. We can also safeguard the future by using our skills to accurately and reliably collect, and ethically share, information about our medical heritage. Keep in mind that medical information is private and the medical genogram you create should be treated with the same degree of respect as your own medical record. This is not meant to deter you from the quest for information, but to caution you about its sharing. After all, with your newfound knowledge the life you save may be your own!

Notes

[1] L. A. Mucci et al., “Familial Risk and Heritability of Cancer Among Twins in Nordic Countries,” Journal of the American Medical Association 315 [2016]: 68-76. Abstract accessed at http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2480486 on 30 May 2016.

[2] Sanjay Gupta, “Are you a Functional Alcoholic,” Everyday Health, accessed at http://www.everydayhealth.com/sanjay-gupta/are-you-a-functional-alcoholic/ on 30 May 2016.

[3] World Health Organization, “Genetics and Asthma,” http://www.who.int/genomics/about/Asthma.pdf, accessed 30 May 2016.

[4] National Human Genome Research Institute, “Your Family Health History,” url: https://www.genome.gov/pages/education/modules/yourfamilyhealthhistory.pdf, accessed 30 May 2016.

Ann,

Many doctors ask for information similar to this, but in list form. There usually isn’t room to lay it out properly. I, for instance, am a breast cancer survivor. So was my mother, and her mother. Her paternal grandmother died of it. Only in the case of my mother and myself do we know the type of cancer. Another genetic disease has come down in the family from a gg grandparent to at least myself and two first cousins and in all probability two third cousins. Putting all this in a genogram like this would, I’m guessing, make it a lot easier for a doctor to grasp at a glance. Trying to cram it into a few too-short lines on a form has always been frustrating. If I create a genogram, just as I do a list of my medications, and give a copy to my doctors, I’m guessing most of them would appreciate it. Thanks for offering a format!

Doris

Oddly, one of the reasons my family gave for doing genealogy (this in the mid-20th century) was so that we knew what diseases ran in the family. Probably spurred by a medical study done on my extended family in the 1930s to track a hereditary skeletal anomaly (and again in the 1990s to run the genetics), and several severe cases of heart disease, including some sudden deaths at young ages. Thus my first chart at about age 12 listed all the people of several generations and what health issues they had. I did my chart for my science class, and I can’t recall my teacher’s reaction, but my extended family was impressed. Many copied it down (by hand, of course, no scanners or copiers then!). We are still at it. I encourage others to do this. It is a shortcut for your doctor in diagnosis, and a heads up for family members who might be at risk.

I think it’s important to remember that a death certificate may/may not record the real cause of death. There was an interesting article in the New Yorker (google Final Forms – The New Yorker), that noted that most death certificates are completed by people who may be in their first year of residency or interns and have little knowledge of the person or their death. And older deaths may have been caused by diseases as yet unknown to the doctor attending the patient. It’s really a very interesting article.

This is so important. My maternal and paternal families have so many people who presented cardiac problems. And I now carry on the traditional, although that did not become apparent until my mid-70s. (Now 82 and appears likely to require bypass surgery of a more difficult kind.) But somehow we overlooked thinking or talking much about this until the probabl e results became apparent. My father died at age 41 after many years of barely escaping death due to his congenital heart condition. It seemed to have skipped me, his only child. But now it appears to have struck with a vengeance my son’s children, many of which either died before birth or sometime afterwards, suffering searing heart problems. Had we put this together, my son would not have agreed to have more children without serious consultation with doctors knowledgeable of these issues.

I had expected twins for my first pregnancy, but lost one at about 2 months. Too naïve to understand what had happened, it went unrecorded and unnoticed. My son’s wife gave birth to twins, but one was already dead from a heart condition. The other baby had to be flown to another state to save her life due to a heart condition. (It forced them into bankruptcy for the expenses.) The surviving twin has now given birth to two healthy babies, but then gave birth to twins with the same problems she and her twin had experienced, except that both were born live. Both have heart defects. Both narrowly survived, with one doing fairly well, but the other severely disabled for life.

There are also mental health problems. In my husband’s family, my research has brought to light many unpleasant facts about an important family member, courtesy of explicit newspaper reports of the events. One can only assume these facts were covered up as they are news to most of the family and coldly received by others. A closer look reveals the possibility that some form of mental health problems are in this family, both in prior generations and in subsequent ones. In my families, there is a history of alcohol abuse and some suicides. Some of these tendencies or traits may well show up in any generation before or after. Today I hope we have a better understanding of mental health and can use this information to help current and future generations.

Hopefully, our goals will be to present accurate and fair histories of our families.