[Editor’s note: Alicia’s probate series began here.]

On the same day that the letter of administration and bond were made, 4 April 1787, the judge appointed three men to take the inventory of Joseph Alden’s estate: Joshua White, Esq., Seth Eaton, yeoman, and Silas White, yeoman, all of Middleborough.

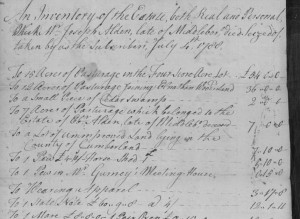

Inventory

The original inventory is in the probate file and a copy is in the copybook, which can be easier to read but should be compared to the original when one exists. In the copybook version in this case, the real estate was subtotaled, showing the curious fact that Joseph’s personal estate totaled £106.2s.2d. and his real estate totaled £106.10s.

Joseph’s real estate is itemized: 15 acres pasturage in the “Four Score Acre Lot,” 12 acres pasturage “joining Elnathan Woods Land,” a small piece of cedar swamp, 7 acres of pasturage “which belonged to the Estate of [his son] Ebr Alden, late of Middlebo deceased,” and a lot of unimproved land “lying in the County of Cumberland [Maine].” From deeds we learn that Joseph had already sold all of his other land, including the farm his father had given him, to his sons Abner and Eliab in May 1781.

Three pieces of “property” other than land are included: a pew (location not given), a pew at “Mr. Gurney’s meeting House,” and a horse shed (probably near the meeting house – parishioners who came from a distance to church were allowed to build shelter for their horses to stand in during the services). Parishioners owned their pews in the church and they could be inherited and sold.

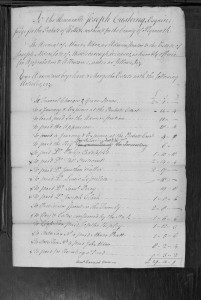

On 2 March 1789, Abner Alden submitted an account (which is in the probate file, but not the copybook) that included funeral charges, costs for his travel to the probate court, payment to the appraisers, payments to six doctors, provisions for the family and the livestock, state taxes paid, costs of recovering debts owed to the estate, and debts paid by the estate. This totaled £45.12s.8d. and Abner reported that in addition to the £106.2s.2d. of personal estate in the inventory, he had collected £109.7s.2d. in debts with £62.14s.6d. still due to the estate.

Often the probate includes division of the real property and/or allocation of both personal property and cash among the heirs as directed by the judge or by a committee of three men appointed by the judge, but in this case, there is nothing about how the estate was divided. Turning to deeds again, we find that on 29 August 1789 the widow Deborah Alden (step-mother to the Alden children) quitclaimed her dower rights in the estate for £34.17s.2d. This deed identifies the heirs as Abner and Eliab Alden, both of Middleboro; Lewis Hall and his wife Fear, Lois Alden, Orpha Alden, and Polly Alden, all of Raynham; Hannah Alden of Bridgewater; and the minor children of Ebenezer (Joseph, Ruth, and Ebenezer Alden under the guardianship of their maternal grandfather, Joshua Fobes, and paternal uncle, Abner Alden).

In August 1811, when two Alden cousins, Noah and Amasa Alden, needed to clear title to “a certain strip of land from Seth Eaton’s house to near the house of Levi Murdock,” they acquired a quitclaim from some of Joseph’s heirs: Abner Alden of Bristol, Rhode Island; Elias Alden of Cairo, New York; Lewis Hall and wife Fear of Raynham; and Samuel Paddleford and wife Lois of Taunton, for a total of $10.[1] These quit claims from scattered family members may be some of the best discoveries any genealogist can find.

Next, we will conclude with a look at guardianship records.

Note

[1] Refer to Esther Littleford Woodworth-Barnes, comp., and Alicia Crane Williams, ed., Mayflower Families Through Five Generations, Volume 16, Part I, John Alden (Plymouth, Mass.: General Society of Mayflower Descendants, 1997), 379-80, and the sources cited therein for more details.

Great series! After carefully reading estate settlement documents on my Seward line, a division of property in 1845 in Ohio turned out to be very interesting. The division stated that one of the girls was entitled to an equal share of property, like the other children. However, prior to reading the document, it was not clear that she was indeed a daughter, but perhaps a grand daughter as her birth was not recorded like other siblings. There is still some question because she could have been an illegitimate daughter of one of the sons, which at this point is likely, also based on her birth year. It is complex, but the fact that she was awarded an equal share of property, and that one of the sons (who could have been her father) declined to receive his share, is certainly interesting. There were lawsuits of brother vs. brother as part of this situation as well. Ah, the intrigue!

I also look forward to the guardianship record post.

Carole, verrrry interestingggg, indeed!

Carole, in the list of family members receiving bequests from my 5th great grandfather, was one daughter who wasn’t listed in any other document. I finally found her to be the widow of his deceased son.

Probate records sometimes can solve the mystery around colonial military deaths. In two cases of men who have no death record in town vital records, the probate records–in one case the deceased’s wife’s accepting administration, and in the other the siblings’ quitclaim deed of their brother’s estate–told the campaign in which they died, and for one even the date and name of the battle (Battle of the Snowshoes). My reaction in both cases was– OMG!!!!!! What a thrill!

But what is the reason for 18th century military deaths not being reflected in a town’s records?

Everybody must have known eventually. Seems pretty cold. Any possible explanations?

Eileen, many possible explanations. One of the most likely is that because they did not die in the town and the clerk had no official notice of the death, he did not enter it on his records.

Thanks, Alicia. I suppose that is the case. There are two local records of young men who died in military service–one “in the spainish expedition…as they hear…in the island of Jamaica” in 1740, and the other “in his majesties service up Mohawk River” in 1759. But there were so many others who served from this community in the colonial wars.

And thank you for doing these series on probates and deeds. You are answering so many questions. Looking forward to info on guardianships.