[Editor’s Note: Alicia’s series began here and continues here.]

It is not often that a will is contested, but in the case of John Dickson, we have a nice, brief example.

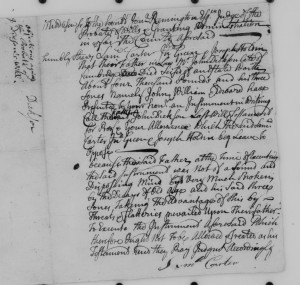

John died on 22 March 1736/37, and by 4 April 1737 a formal petition had been submitted to the judge of the probate court by Samuel Carter, John Green, and Joseph Holden claiming that “their Father in Law Mr John Dickson late of Cambridge Decd Died Seised of an Estate Worth About four Thousand Pounds and his three sones namely John, William & Edward have Presented to your honr an Instrument in Writing Call[ed] their Father John Dickson[‘s] Last Will & Testament for Proof.… [The petitioners] beg Leave to Oppose – because their Said Father at the Time of Executing the Said Instrument was not of a Sound and Disposeing Mind but Very Much Broken by the Decays of Old Age and his Said three Sones Taking the Advantage of this by – Threats & flatteries prevailed Upon Their father to Execute the Instrument Aforesaid Which therefor Ought Not to be allowed….”

Samuel Carter was the husband of the youngest daughter, Margery Dickson. John Green was the second husband of the oldest daughter, Jane (Dickson) Robbins, widow of Joseph Robbins. Joseph Holden was the second husband of second daughter Elizabeth (Dickson) Russell, widow of Hubbard Russell. Clearly they all thought the payments ordered to the daughters in John’s will were insufficient.

On the same day the judge ordered the heirs of John Dixon to appear before him at his house in Cambridge on the next Monday at 10 o’clock, or, for the heirs who could not make that date, to appear on 23 May. William Dixon was ordered to serve the warrant to the rest of the heirs and report back to the judge, which he did. On the morning of 23 May, another warrant was issued to James Butterfield Jr. and John Butterfield of Cambridge to appear at 10 o’clock to testify regarding what they knew about the decedent’s state of mind, and on 6 June a third warrant was issued to Samuel Whittemore, Jonathan Butterfield, John Butterfield, David Dunster, Ebenezer Cutter, Joseph Russel and wife, Jabez Carter, and Joseph Belknap to give more testimony. Unfortunately for us, the oral testimony given was not recorded. All we know is that whatever was said on 6 June was sufficient for the judge to admit the will and issue the orders for probate on that day.

The decision could have been appealed to the Middlesex County Court and then to the Supreme Judicial Court, but there is no indication of any further action among the records here. My personal guess would be that once the dissenting heirs were convinced the estate was not worth £4,000, an extremely high estimate, they gave up on the contest.

Next, we’ll look at what is and what is not in the inventory.

A basic question–Where do we find or look for old deeds and wills? Especially in New England and NY in the 16 and 1700s?

Sam, great question. It just happens that NEHGS has an on-line seminar in March about just that topic — New England Land, Court and Probate Records by David Allen Lambert. Information about registration is at http://www.americanancestors.org/education/online-classes

Also see http://www.americanancestors.org/education/learning-resources/read/17thc-new-england-guide

and then there is http://shop.americanancestors.org/collections/new-england-resources/products/genealogist-s-handbook-for-new-england-research-5th-edition

Lots of resources on the open Internet, too.

On Family Search, I came across a one page note attached to probate papers with the mark of my 7-times great grandmother contesting a will of a cousin (presumably) of her deceased husband. She complains that the “Right of Dower in the Real Estate of sd Deceasd which belongs to your Petitioner has not bin assignd and set of[f] to be impound [?] in severalty but remains in Common with the heirs to sd Estate.”

The court issued a citation for her son to appear but nothing more about her complaint is contained in the Probate File Papers. It’s not clear how the complaint was resolved but the real estate ended up in the hands of the deceased’s intended beneficiaries. I wonder if the original files would contain more information regarding the complaint’s resolution.