After the turn of the nineteenth century, the number of medical schools around the world increased significantly. While the increase in these institutions led to monumental developments in the medical field, it also had previously unforeseen consequences. One such consequence was a shortage of bodies for dissection and examination.

After the turn of the nineteenth century, the number of medical schools around the world increased significantly. While the increase in these institutions led to monumental developments in the medical field, it also had previously unforeseen consequences. One such consequence was a shortage of bodies for dissection and examination.

In the early nineteenth century, only the bodies of executed criminals were legally allowed to be dissected, and the number of new medical schools opening their doors in England and Scotland in those years greatly exceeded the supply of bodies available.1 More lenient punishment for crimes resulted in about 50 people per year being executed, a figure which did not meet the needs of medical schools.2

The sudden demand for more bodies of deceased individuals led to “an ever-increasing epidemic of grave robbing for medical use.”3 Concerned family members, inspired by a high profile case in which two men were found to be murdering their lodgers to sell the bodies to medical schools, began forming graveyard watch groups to protect the tombs of their loved ones from being disturbed.4

Despite the formation of watch groups, a growing number of incidents of grave robbing led to the creation of an invention known as the mortsafe. First constructed in 1816, mortsafes were heavy iron and stone devices which were often locked on top of recently filled grave sites to prevent the theft of bodies.5 In many cases, these devices were padlocked together using two different sets of keys which required two people to remove them. In Paisley Burns Club, 1805-1893, the mortsafe of Dundas S. Porteous is described as “a hollow casting of about six feet long and two feet square inside, having a door on the one side.”6 It is said that the weight of these devices served as the most significant discouragement from the robbing of graves, as mortsafes generally weighed over one ton.7 After a period of about six weeks, when bodies were determined to be sufficiently decomposed and, therefore, no longer useful to medical schools, the mortsafes were removed.8

Because they were only needed for six weeks, mortsafes were usually either rented or purchased by burial societies, and their owners charged fees to use them.9 For this reason, there are very few mortsafes remaining, as only a small number were needed (perhaps only one per town or village). Sometimes, these devices were purchased by churches who rented them out to families of the deceased for a fee. The fee for the rental of a mortsafe was usually about 1 shilling per day, or about 2 pounds and 2 shillings for the six weeks they were required.10

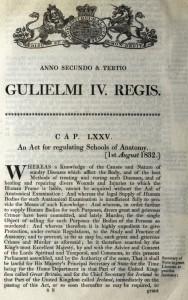

The passage of the Anatomy Act of 1832 played a significant role in the disappearance of mortsafes. This act, passed 1 August 1832, allowed physicians, surgeons, and medical students to legally acquire the bodies of individuals who died in prison, in workhouses, or had donated their body at the time of their death.11 In the text of this act, the Parliament of the United Kingdom acknowledged that the dissection of bodies was necessary to advance medical science, and also that the supply of bodies for such work was insufficient.12 Also mentioned were the crimes committed in the name of procuring these bodies. Therefore, a change was required in order to make bodies more accessible.

The passage of the Anatomy Act of 1832 played a significant role in the disappearance of mortsafes. This act, passed 1 August 1832, allowed physicians, surgeons, and medical students to legally acquire the bodies of individuals who died in prison, in workhouses, or had donated their body at the time of their death.11 In the text of this act, the Parliament of the United Kingdom acknowledged that the dissection of bodies was necessary to advance medical science, and also that the supply of bodies for such work was insufficient.12 Also mentioned were the crimes committed in the name of procuring these bodies. Therefore, a change was required in order to make bodies more accessible.

Today, very few mortsafes remain intact. Given that they were virtually obsolete after 1832, many of these devices were recycled for their metal or left to rust where they lie. Most of the ones that can still be found are located in churchyards in Scotland. Recently, a mortsafe with the body still inside was found buried in a churchyard in England’s West Midlands, surviving as a relic of a brief period of English and Scottish history.13

Notes

1 “The Mortsafe: Or How to Protect Your Loved Ones from Bodysnatchers,” Kuriositas, 28 May 2013 http://www.kuriositas.com/2013/05/the-mortsafe-or-how-to-protect-your.html.

2 Ibid.

3 Anetta Black, “Greyfriars Cemetery Mortsafes,” Atlas Obscura http://www.atlasobscura.com/places/greyfriars-cemetery-mortsafes.

4 Ibid.

5 “The Resurrection of a Mortsafe,” Strange Remains, 22 February 2014 http://strangeremains.com/2014/02/22/the-resurrection-of-a-mortsafe-that-protected-a-corpse-from-body-snatchers-and-saved-the-bones-for-archaeologists/.

6 Robert Brown, Paisley Burns Club, 1805-1893 (London: Alexander Gardner, 1893), p. 190.

7 Dane Love, Scottish Kirkyards (Hale, 1989), unpaged.

8“The Mortsafe,” Kuriositas, 28 May 2013 http://www.kuriositas.com/2013/05/the-mortsafe-or-how-to-protect-your.html.

9 Love, Scottish Kirkyards.

10 Ibid.

11 Medical Dictionary, Free Dictionary, Anatomy Act of 1832 http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/Anatomy+Act+of+1832.

12 Gulielmi iv. Regis, CAP LXXV, “An Act for Regulating Schools of Anatomy” http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/hommedia.ashx?id=8077&size=Large.

13 “Archaeologists in West Bromwich Find Grave-Robbing Evidence,” BBC, 17 January 2013 http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-21044770.

James Bridie’s play The Anatomist, about the 1820s Burke and Hare scandal, is worth reading in this context.

I’ve heard of grave robbing for the purposes of dissection in medical schools. But a mortsafe to keep this from happening is a new one on me. The fact that you even found a picture of one makes it even more fascinating. Thanks for digging it up, Zach!

There is a somewhat similar story about my great-great-grandfather. Hiram Leonard was a farmer in LaSalle Township, Monroe County, Michigan. He died in January, 1881. In this rural farming community, the common practice was to store the deceased, in the casket, in an outbuilding on the farm until the Spring thaw allowed for digging a grave. At the same time, medical schools (some quacky) were popping up in Detroit, Michigan and Toledo, Ohio. LaSalle was only ten miles from Toledo, making it a convenient hunting ground for graverobbers, who did not even have to dig for the cadaver at that time of year. Hiram’s obituary includes the fact that “his body was removed to the mausoleum in Monroe to save him from the ghouls”. His remains were returned for burial in LaSalle the following Spring.

Never heard of a mortsafe but can understand the reasoning. Good story for Halloween this month.