The British constitutional historian Walter Bagehot (1826–1877) wrote that “When there is a select committee on the Queen, the charm of royalty will be gone. Its mystery is its life. We must not let in daylight upon magic.”[1] There is something uncanny about royalty, a mystique that can be hard to value according to its merits. This phrase of Bagehot’s – with its reference to “mystery” and “magic” – came to mind as I was thinking about the question of morganatic marriages in Germany.

For Queen Victoria’s contemporaries among the royal houses of Europe, the idea of “unequal” marriage – one undertaken by two people of differing ranks, generally a royal male with a non-royal bride – was particularly obnoxious. When a member of a royal house married an opera singer or an actress, his bride and her offspring were to have no place in the succession. The bride might receive a title of lower rank than her husband’s, and this could be passed along to their children, but these misalliances were outside the ken of the official histories of the kingdom, duchy, or principality in question.

And, of course, such misalliances – called morganatic marriages – happened with some frequency. Their cost in terms of the participants’ self-respect and future prospects was prodigious, but in general the system was successful in keeping the bloodlines of these royal houses “untainted” by non-royal blood.

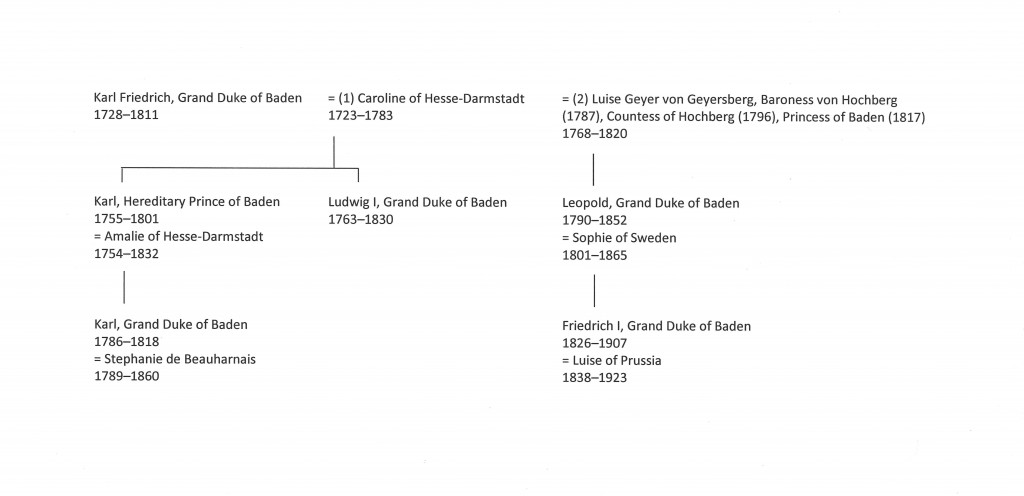

When the succession of the royal house was in question, however, all bets were off. One fascinating example is the way in which the Grand Dukes of Baden (1806–1918) handled the almost immediate failure of the elder grand ducal line (from Grand Duke Karl Friedrich’s first marriage) by turning to Karl Friedrich’s second (and morganatic) wife, the Countess of Hochberg, and her children.[2]

The Hereditary Prince of Baden died in 1801, before his father assumed the title of Grand Duke, leaving a son (later Grand Duke Karl) and six daughters (including the Queen of Bavaria, Empress of Russia, and Queen of Sweden). In 1806, Prince Karl married Napoleon’s adopted daughter, Stephanie de Beauharnais, and three months later his grandfather proclaimed himself Grand Duke. When Karl Friedrich died in 1811, he was succeeded by his grandson, but Grand Duke Karl’s two sons died young and his three daughters could not succeed him when he died in 1818.

Grand Duke Karl’s uncle, Prince Ludwig, succeeded him, but already the grand ducal house had taken steps to address the looming succession crisis. Karl Friedrich had had a second family with Luise Geyer von Geyersberg, who was created Baroness von Hochberg in 1787 and Countess of Hochberg in 1796. Soon after taking the rank of Grand Duke, Karl Friedrich had included his Hochberg children in the succession to the Grand Duchy, and in 1817 his widow and their surviving children became Princes and Princesses of Baden.

Grand Duke Ludwig died in 1830, at which point he was succeeded by his half-brother, born Leopold Freiherr von Hochberg in 1790. A Prince of Baden from 1817, Grand Duke Leopold took the not-uncommon royal step of marrying his great-niece, Princess Sophie of Sweden, in 1819! In due course Leopold and Sophie’s son, Grand Duke Friedrich I, married Princess Luise of Prussia, daughter of Wilhelm I, Emperor of Germany – Friedrich’s unusual pedigree was evidently no bar to an alliance with the ruling family of a newly united Germany.

All of which is to say that the offspring of such marriages could be both attractive and useful. Two other examples come to mind: the father of Princess Victoria Mary of Teck (1867–1953), later Queen Mary, was the product of a morganatic marriage,[3] and the Queen’s good looks and good sense could well be attributed to her father’s family. In the same period, Queen Victoria’s granddaughter Princess Victoria of Hesse-Darmstadt married her cousin Prince Louis of Battenberg (1854–1921), of a non-dynastic branch of the Hessian grand ducal house: their children included Princess Andrew of Greece and Denmark, the mother of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (1921–), and Queen Louise of Sweden, not to mention Earl Mountbatten of Burma (1900–1979), the last Viceroy of India.[4]

Notes

[1] Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution and Other Essays, rev. ed. (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1884), p. 127.

[2] Burke’s Royal Families of the World, 2 vols. (London: Burke’s Peerage Ltd., 1977–80), 1: 196–99.

[3] Ibid., 184–85.

[4] Ibid., 213–14.

Morganatic marriages have always fascinated me, and thanks to both morganatic marriages and to cross-social class liaisons resulting in children, I have royal cousins through my German grandmother that commoner folk would not normally be linked to by blood. (As described in my forthcoming article in American Ancestors.) Sometimes love conquered all even in the most rigid of royal or aristocratic families. Thanks for this, Scott!

Thanks, Grant!

Morganatic marriages could involve not just obvious mésalliances, like an opera singer or an actress, but also brides of non-royal nobility. In the old days, Diana, as the daughter of an earl, would have been considered morganatic for a royal groom, especially for the heir to the throne, as least by European standards. The classic example is that of the Austro-Hungarian imperial heir.

Thanks, Gerald! Certainly in European royal circles, both Lady Diana Spencer and Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon would have been considered ineligible to marry a future monarch.

Queen Victoria had little time for such views, and generally recognized the marriages of her female subjects to foreign royalty — and, of course, allowed her younger daughters to marry the Duke of Argyll and Prince Henry of Battenberg, neither groom of suitable rank by German royal standards.

Edward VII and George V’s daughters, successive Princesses Royal, married non-royal British peers — and in the case of the former, the daughters of the Duke and Duchess of Fife were given the novel rank of HH Princess of Fife. Both George VI and his brother the Duke of Gloucester married Scottish peers’ daughters, so by the time of Charles and Diana such alliances were perfectly normal — even a bit old-fashioned!

Thanks, Scott. Fun read — now; of serious consequence then, even if always farcical. I’d say Kate Middleton, with William co-conspiring, is out to achieve Walter B’s objectives (keeping the family business going) by turning them upside down. Going for “a little Harry in the night” & day & every week. The Badens went only 90 degrees. (Principles! I say, Principles — ah, more like guidelines, me poppet.)

My mother’s father’s family were early 1870s migrants from Baden. They seem to have arrived as part of a church membership following a charismatic minister who set up shop in New Haven, as his people where tradesmen/mechanics and not farmers. (Bob Anderson’s “ministerial companies” never really stopped coming to the New World.) Families drifted off pretty quickly to other CT cities and towns and on to other religions. Moving, recombining, moving again–the American story.

Hello Robert and Scott, this is great! I always enjoy posts from both of you.

My mother’s paternal ancestors migrated from Renchen and Unsbach in Baden in the 1870s, and my husband’s paternal ancestors reportedly came from Kreishiem, Baden, through the efforts (or inspiration) of William Penn, and settled in Pennsylvania in perhaps the 1670s. In the case of my mother’s ancestors, I never considered whether they came with a religious leader as part of a “ministerial company.” Great hint! Thank you.

As long as we are referencing the British royal family, I’m waiting to see, if and when Prince Charles becomes King along side his wife Camilla Shand Parker Bowles, whether she will be referred to as “Princess Consort” (according to the official statement when they were engaged) or given the title of “Queen.” Scott, is their marriage properly considered a “morganatic” marriage?

Thanks, Candy! In my view, Charles and Camilla’s marriage is not morganatic — both because morganatic marriages are not recognized in UK law, and because they married in Berkshire with the permission of the Queen, permission given in spite of their respective divorces.

I suspect that, when Charles succeeds, they will become King and Queen, and that the titles Duchess of Cornwall/Princess Consort will be quietly dropped: the novel titles were used to quiet public discomfort about there being a second Princess of Wales during the reign of Queen Elizabeth II.

Scott, I suspect you are (alas!) correct, and that Camilla will be crowned “Queen.” Thanks to NEHGS and Gary Boyd Roberts, I learned that I share several New England ancestors with Diana Spencer, the first wife, so I’m not a fan of the second wife!

Camilla is being allowed to wear many pieces of royal jewelry — including some of my favorites, the “Honeycomb Tiara” so often worn by the Queen Mum, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon and major necklaces — never allowed to Diana, which I find quite telling. (So much private royal jewelry is loaned within the family, not given, like the “Halo” tiara Kate Middleton wore for her wedding, worn previously by Princess Margaret, Anne The Princess Royal, and so on.) I suspect Queen Elizabeth II herself decided that Camilla should not publicly anticipate being crowned “Queen” for the duration of her reign, knowing perfectly well that when and if Charles succeeds her, he will countermand that. Hmmm, what would Victoria think? (Thanks for indulging my fascination with the British royals and their jewels.)

So, back to Baden ….

Hmmm I just saw the census for my Schlieker,Tappe, Pontius families, and they listed their place of birth as “Baden” & Prussia, and I wondered, “where is that” and how do I research this family??

I am a Pontius descendent, too. This organization has a lot of information and help:

http://www.pontiusfamilyassociation.org

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margraviate_of_Baden