[Editor’s Note: As part of the Society’s commitment to serving as a repository of original documents, preserving (and, when necessary, conserving) them for future generations in all their forms, NEHGS has a state of the art document conservation laboratory about which both Jean Maguire and Deborah Rossi have written for the blog.]

From Conserving an historic family tree by Deborah Rossi:

“NEHGS is always looking to acquire family trees to add to our collection. They come to us through donation or purchase, and their condition on arrival varies from pristine and framed to dirty and frayed. Many a family tree crosses the threshold of the Society’s new Conservation Lab, where it is cleaned and repaired, resulting in a piece which can be safely stored or displayed.

“The Lathrop family tree, which was featured in the Fall 2013 issue of American Ancestors magazine (p. 64), is a recent acquisition and can be used to demonstrate some of the preservation steps…

“When the Lathrop piece was removed from its enclosure, the first task was to remove any surface dirt. We used a Chinese bristle brush, moving from the center of the piece outward. We then used a plastic eraser to remove additional surface dirt. There were also paper tears needing repair. This was done by using wheat paste to attach strips of Japanese paper on the back of the piece, thus stabilizing the paper of the family tree.

“Dry surface cleaning was sufficient for this piece, but in some cases a piece must be washed. General practices for aqueous treatment of paper are to submerge the piece in a bath of distilled or de-ionized water (whichever is available) for a period of ten minutes. This process may have to be performed a few times until the object in the bath no longer retains any signs of dirt. This does not, as you may fear, dissolve the paper. However, I would not recommend doing this at home.”

From Conserving some NEHGS treasures by Deborah Rossi:

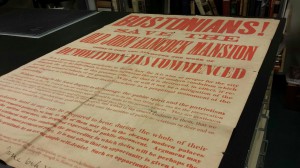

“One of the things I like most about my job at the Society is that, because we are such a small operation, we tackle a wonderful array of projects. For example, for the past month I have been cleaning and backing this 29” x 42” broadside [shown above left]. It was an announcement made/published by T.G.H.P. Burnham on 6 June 1863 to protest the already-begun demolition of the John Hancock mansion. Sadly, the protest amounted to just that; where the mansion once sat is now the west wing of the early twentieth-century addition to the Massachusetts State House. To my knowledge, the only surviving external piece of John Hancock’s home is the [exterior] stairs, later incorporated into the embankment of Jamaica Pond and leading to the former Perkins estate.”

From Behind the scenes in the Conservation Lab by Jean Maguire:

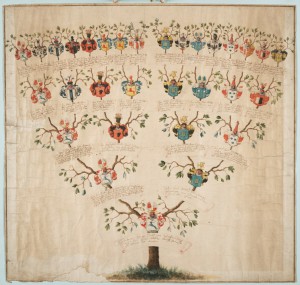

“When large color-illustrated items like pedigree charts, maps, and family trees come into the Conservation Lab for treatment, a digital photograph is taken before any other work is carried out. The next order of business is to review the condition of the piece. The von Wolfframsdorff chart [at right] appears to have been rolled at one point and suffered a great deal of mishandling before it arrived at NEHGS. There are many wrinkles throughout the piece, indicating that it may have been pressed down or bent when rolled up.

“Many of the tears on the outside edge were mended with a one-inch strip of paper matching the paper of the chart and adhered to the back with mucilage glue. The strips will be removed and replaced with Japanese mending tissue known as kozo to improve the repair. The mending will be lighter in weight without compromising the strength of the repair, and it will be less noticeable. Missing pieces along the outside edge need to be infilled – a process of replacing paper where it has been lost…

“In spite of the chart’s history of mishandling and the acidity in the paper, the colors of the gouache paint have remained remarkably vivid. Paint is always tested in the lab before any item receives water treatment, and in this case we can see that the green gouache would bleed, and therefore water treatment will be limited…

“The von Wolfframsdorff chart will be put back into its original frame, but the housing materials will be traded out for acid-free ones, and a barrier will be created between the glass and the object. It will be returned to its place on the wall here at NEHGS, stronger and healthier thanks to the time it spent in our version of a hospital/spa for treasured books and manuscripts.”

What should a person do with their unfinished family genealogy notes, etc., when no one else in the family is interested in carrying on the search? Should they make a note in their will that the information be donated to their local genealogy society so others in the future can look at them for research?

My gr.daughter is headed off to college this August and is majoring in Anthropology – at Miami of Ohio; thus, recognizing she had special interests, I designated her to receive the family genealogy records. All one can do is hope that someone in the family has an interest in genealogy and pray your work carrys-on!

On the other hand, I wish I knew where some notes were. My grand aunt’s husband hand drew a descendancy chart for 10 generations, which also includes three other interconnected families. The full chart is 40 inches wide by 30 inches high. I have used that plus many other sources to have a 13 generation descendancy chart (and book). But, as I said, I would love to have the notes from the original chart; I have asked many members of that branch but to no avail.

I’m getting older and have so many files of notes and documents which are way too bulky for any one person to keep after I am gone. I have been able to keep it all because I’m single and choose to use “extra” space to house these things, but the upcoming generation is SO invested in “Less is More.” So, I’ve put in my will that the information for family lines which pertain to certain places are to be donated to that place’s University, Genealogy Association, or other interested place. Besides being in my will, it’s also notated on each box for my executor to follow through. That way, the notes will be available for a long time to whatever presently unknown family and/or researcher might be able to use them. The gifting of these things is the only guarantee of preservation. Perhaps there could be some more articles about this topic? My generation is dropping like flies and our files usually simply disappear with us.