A great way to begin tracing your family history is to interview living relatives, asking for relevant birth, marriage, and death information. These interviews sometimes yield specific information (or at least an estimate), and you can then contact the appropriate authority to provide a copy of the original vital record.

But what do we do if grandma’s information fails to lead us to a vital record? Surprisingly, this is more common than you’d think, as people often misremember facts or were told the wrong information from the get-go. In this case, grandma may lead us on a wild goose chase trying to track down the correct location and/or date of a vital record. This may be especially annoying if the record is more recent, as statewide indexes for modern vital records are less common. To locate these modern vital records (civil records), we must first look for an alternative record to point us in the right direction. Here are some examples:

- U.S. Federal Census or state census. While census records often include birth and marriage information in terms of ages (e.g., how old were you at your first marriage?), they can provide enough information to determine when and where an event occurred. For example, if a person disappears from the census, or the spouse is listed as a widow, he or she may have died between enumerations.

- Social Security Death Index. The SSDI is the closest researchers come to a national U.S. death index (even though each state complies with the index differently). The index provides an exact birth date, as well as the month and year of death. Using this record group, you may also want to order your recent ancestor’s Social Security Application (SS-5), which will include parents’ names and employer information. (See “Tips for using the Social Security Death Index.”)

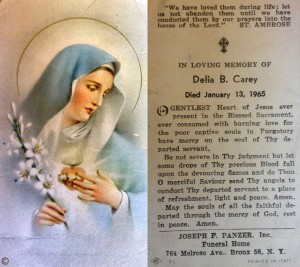

- Funeral prayer cards. My grandmother has a collection of these prayer cards, which gave me information about the death of several people, including my great-grandmother, Delia Bridget Carey. To locate funeral prayer cards, check with other family members, as well as local libraries, archives, and historical societies. (NEHGS has some funeral prayer cards in the R. Stanton Avery Special Collections.)

- Newspapers. Birth notices, marriage announcements, and obituaries are often printed in the newspaper. Several sites have large collections of digitized newspapers, such as GenealogyBank, Newspaperarchive.com, Newspapers.com, Google News Archive, and the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America Collection. To locate local newspapers, check with the local library.

- School records. Yearbooks, class books, and alumni directories often include personal information about students, such as their birth dates and spouses’ names. NEHGS maintains a large collection of class books for Harvard and Yale, as well as other colleges and universities; Ancestry.com has a database of U.S. school yearbooks from 1800 to 2012.

- Membership cards/applications. From the Masons to the DAR, membership cards/applications often provide specific information about their supporters. If your ancestor belonged to a society, you should research whether the organization maintained membership records.

- Bank or insurance records. Follow the money! If your ancestor invested, or held a bank account, his or her birth, marriage, or death information may be included in the records of that institution. For example, the records of the Massachusetts Catholic Order of Foresters (MCOF) contain a wealth of information, including the names of the insured’s children and parents.

These are just a few of the modern alternatives; many more exist. Tomorrow I will outline some of the common vital record alternatives for older generations, such as probate records and cemetery stones. Don’t forget to tune in!

We may speculate on things as well that Grandma never told us. For example, my Grandma Mary Wood Small was so dark that she looked “ethnic”. But she never revealed herself to be other than Irish and her family immigrating long ago from County Cork with a bit of Scots- —-Campbell and the poor side of the Argyles in the mixture. Because of her family names “Wood” and “Wing” an hypothesis was developed that she had to have American Indian in her….. in fact her own grandmother was a full blood so goes the theory. When I did genetic ancestral testing I was totally surprised that nothing “native ” was found….. other than a discovery that I am as French as I am German …. a nice touch to add to my known British Scots- Irish and German ancestry. And as far as the darkness . I am discovering a lot of the Wing side as in “Winge” is “dark”. Now if I could just figure out my French ancestry !

I always “knew” that my maternal grandmother was born on May 12, as that’s when we celebrated it. When I went to my grandmother’s hometown in WI in the 1970s looking for family gravestones, however, I stumbled on my grandmother’s original baptismal record. It showed her birth date to be May 13, not May 12. The pastor of the church holding the records told me that often 19th c. families were off by a day or two. Looking up my grandmother’s first birthday in a perpetual calendar, I discovered it fell on a Friday the 13th. So my surmise is that, Norwegians being as superstitious as anybody else, the family celebrated her first birthday on the 12th. She was from a large family, and eventually, her birthday “became” the 12th. So far, I can’t prove this hypothesis, as births weren’t recorded in WI back that far. But it makes a certain amount of sense out of an inconsistency between the only record we currently have and when her birthday was celebrated when she was an adult.

This must not be uncommon. I have one grandfather who celebrated on the 19th, as stated on his late-filed birth certificate; but his original one says the 21st. (Must not have been able to locate the original during WWII, so she filed a late one; but he must have celebrated on the 19th all his life). Have a grandmother who celebrated on the 27th all her life; her original certificate says she was born on the 28th. I usually remember the rule of thumb is to go by the most contemporary record, but it is a mystery, one which neither of them could answer. Then there’s the mystery of why my other grandmother’s certificate says her mother’s name was “not stated”. Not her father, her mother…….

These are good alternatives honestly in tracing your ancestors. It’s quite fun to know where we came from.

In spite of a “wonky” recorded and repeated family genealogy on my dad’s Hayhurst lineage, no one had listern to granddad William Hayhurst. He always said and told others that his father was from England and migrated as a very young child with his parents. To my astonishment I found the passenger list on the Montezuma that had departed from Liverpool UK mid Feb. 1850 and landed at the port of New York, March 11, 1850 that listed a three young old William and his parents Edward and Catherine Curran Hayhurst as his parents (apparently a younger son, John was a “stowaway”. In tracing the family back in England, Manchester Cathedral was the site of the baptisms of all the males and the marriage of the couple. Further investigation actually in Manchester, found that Edward’s parents were married in a Catholic Parish and John, the father, was a local “Publican”– that is, he either owned or managed a pub. The so interesting thing on the ship records, they listed the family as “Irish”. Not sure why? While I would assume that they had some Irish Catholic roots, they were actually very Church of England and recently online I witnessed an baptismal service at Manchester Cathedral using the same Font that they had all used.

Thank you for giving knowledge that all you mentioned can be useful to us to trace family. Nice post!

Thank you for sharing the list of alternative documents. This is a helpful article!

This is a great article. Full of information! Many people have trouble with vital records. This is helpful for them.