Do you have an ancestor from New Hampshire who was working at sea at the young age of 10 or 12? Have you seen a U.S. Federal Census record that states that your ancestor was a “mariner” at age 13? Did you think it was a mistake or an oversight? In fact, many boys as young as 10 were working on ships in New Hampshire in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

After the close of the Revolutionary War, shipbuilding and commerce along the Piscataqua River in New Hampshire flourished. The merchants and traders of the ports along the river were quick to profit because they were no longer subject to direct British restraint. This was in stark contrast to earlier times as Portsmouth, New Hampshire, did not own a single square-rigged vessel in seaworthy condition before the close of the war.[1]

Ships, brigs, and schooners were constantly loading and discharging cargoes at the various wharves along the Piscataqua and Cochecho Rivers in New Hampshire. Outgoing cargo included fish, lumber, beef, and pork, plus live animals such as horses, mules, oxen, sheep, pigs, chickens, geese, and turkeys. The ships also traded and sold swords, guns, spyglasses, and other wares made locally. The ships returned from far-off locales bearing molasses, sugar, wine, and “sundry European goods.”[2]

There were also localized river traffic and occupations involving shipping in New Hampshire. From 1783 through the 1820s, many stores selling various goods opened along the waterfronts. Local trading was augmented during this time, and gundalows and packets plied the waters daily on scheduled runs to and from Maine and Massachusetts, delivering both freight and passengers to various destinations along the coast.[3]

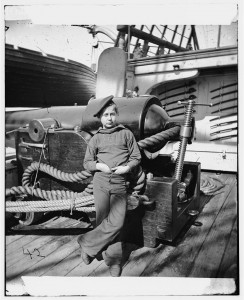

Some ships leaving New Hampshire were not trading ships but rather warships. In 1799 and 1800, the Portsmouth and the Scammel were launched from New Hampshire for the purpose of sailing the West Indies looking to capture French armed ships and to recapture American prizes lost years earlier during the war. Young men on these ships were employed as “powder monkeys,” carrying gunpowder from below deck to the gun deck and artillery pieces, either in bulk or as cartridges, moving with speed and agility.[4] When not in combat, the powder monkeys served as personal assistants to the officers, cook’s helpers, and general helpers for whoever needed them, assigned to whatever odd jobs needed to be done aboard.[5]

If you are researching your ancestors and come across a 12-year-old who worked as a mariner, remember that the age is not a misprint: working at sea at such a young age was certainly possible in the 1700s and 1800s.

Notes

[1] William G. Saltonstall. Ports of Piscataqu: Soundings on the Maritime History of Portsmouth, N.H. (New York: Russell & Russell, 1941), p. 118.

[2] Saltonstall. Ports of Piscataqua, p. 142.

[3] Robert A. Whitehouse and Cathleen C. Beaudoin, Port of Dover: Two Centuries of Shipping on the Cochecho (Portsmouth, N.H.: Portsmouth Marine Society, 1988), p. xii.

[4] J. Arthur Moore, “Powder Monkey and Ship’s Boy,” website of Up from Corinth: Journey into Darkness, at upfromcorinth.com/blog/powder-monkey-and-ships-boy-2.

[5] Brian Lavery, Nelson’s Navy: The Ships, Men, and Organization, 1793–1815 (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1989), p. 88.

I was surprised to see the statement that ships built in New Hampshire were sent out to capture French armed ships. The French had only 20 years earlier saved our bacon at Yorktown and became a lasting friend to America.

Such as the ironies of war…… the United States still has a difficult time in accepting that it was the French Navel forces at Yorktown that actually won the American rebellion and not Washington and his ill fitted militia. The French accrued a huge financial cost for their involvement in America’s rebellion …. which unlike the French Revolution ….. was only a rich man’s , mostly mercantile traders, rebellion !

It was the PRE-French Revolution that helped us. They were overthrown by the ones whose ships our privateers and naval vessels were going after.

Midshipmen, powder monkeys, and “ship’s boys” in the British Navy were often pre-teens during the 17 & 18 hundreds.

Such could be said about all of the British North American colonies …… this is by and large how seafaring skills were acquired !

A cousin of mine thought our joint great-great-grandfather, born along the coast in Wales, was pulling a fast one claiming to have gone to sea at the age of 10 after the remarriage of his widowed father. This would have been 1842 or 1843. (Having grown up learning something of maritime history, I do not find this as particularly unusual for the time and place). In my gggfather’s own words, on one voyage, to be his last, he “fell in” with a family going to join the Mormon migration, and married their daughter on board. They landed in probably New Orleans, then traveled up the Mississippi to Illinois to join the Mormon migrations there. (The marriage on board is not yet directly documented, but married they certainly were.) Their names appear in the records of one of the migration “companies” that went west to Utah. Research into his early life is complicated by someconfusion in the family records in Wales (nothing new about that), and the fact that somewhere along the line he seems to have changed his surname from the Welsh “Jones” to the English “Jackson”. Certainly by the time he appeared in America he was Jackson.

Annie, you might enjoy reading the historical novel The 19th Wife. http://www.amazon.com/19th-Wife-Novel-David-Ebershoff/dp/0812974158/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1426176474&sr=1-1&keywords=the+19th+wife+by+david+ebershoff

There is a section of the book where the story is about going overseas to recruit people from Europe. Lots of factual Mormon history woven into the novel.

Thanks– I have read it, and I confess it didn’t tell me anything I didn’t already know. The history of the mormon culture is not a comfortable history. Though one doesn’t hear much about it, the resulting stresses are strong within the culture, which is no longer as isolated as it once was. I grew up in a family with many apostates and non-practicing mormons, as well as those dedicated to the church. It made for an interesting (and challenging) childhood. No novel can beat what I learned and experienced growing up. The question that keeps nagging me now, though, is this one: what were the circumstances and drivers that drove so many of my ancestors to converge in a relatively short time period from many points in the US and Territories, and some directly from the British Isles, to converge toward each other as part of a religious movement like the LDS? What were they seeking? What were they leaving, and why? There is a largely unexplored stpry there that grew out of the same unsettled dynamics that were at work in the emerging United States. I would like to understand those dynamics better, and I think that the best way to do it is to study the larger culture first, to see how that particular period influenced what would become the mormon culture.

Annie–have you looked at the history of “the burnt over district” in New York, where Joseph Smith had his revelations? The Mormons and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) are two very different churches that came out of NY in the religious ferment of that time period. That doesn’t explain all your other ancestors attracted to the Mormons, but I’ve found that history helpful myself in such understanding as I have of the LDS. I have none among my ancestors, but have cousins who are converts, and friends whose ancestors go back to Brigham Young, but who have left the Mormons.

My gggdad signed on ship from Lubec, Maine at the age of 13. He got lucky: the capt. insisted he finish his schooling on board. Went round the cape up to California, overland to Nebraska and signed on to help build the UP RR. He learned the value of a good education from that man, and believed in it so much he built two country schools on his own land in Colorado, and at the second one installed his daughter as teacher. I’ve always got the impression that American ships weren’t nearly as “bad” on young men as the Royal Navy.

Now that Doretta mentioned a novel, I thought of “The Captain’s Wife”, which would also tie in to the recent article on “Deputy Husbands”. A good read! So is Dana’s “Two Years Before the Mast”.