My great-grandmother was one of a large family, and when her mother died in 1924 the family house was evidently broken up, its contents divided between Wally and her nine surviving brothers and sisters. A fascinating family register, listing my great-great-grandfather’s twenty-three children and (most of) their birthdates descended to the youngest daughter: her granddaughter, my second cousin once removed, now has it. My great-grandmother Wally received a curious trove of documents associated with her father, a well-known musical instrument-maker: her portion included an 1845 passport from the Grand Duchy of Baden, an 1863 receipt for a soldier substitute, and an 1899 condolence letter from William Boucher Jr.’s half-brother to his widow.

These papers descended to my grandmother, to my mother, and then to me. They are like Brigadoon, though, as I’ve had them, misplaced them, had them, and (for now) misplaced them again. They are almost certainly lurking on a bookshelf in my apartment … but which one?

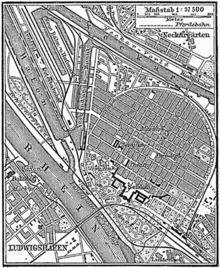

The passport would be nice to find, as it would settle a current argument. When registering the births of a number of his children, William Boucher Jr. (1822–1899) listed his birthplace as the City of Hanover in the then-Kingdom of Hanover, since 1871 a part of Germany. This conflicts with the passport, which states that he was born in Bielefeld, a suburb of Mannheim, in Baden.

Based on this information, in 1981 I visited Mannheim and found my way to the City Archives, where I had an awkward but ultimately successful talk with the archivist in my fractured high school German. He found my great-great-great-grandparents’ 1822 marriage and the birth, later on that year, of my great-great-grandfather in Bielefeld. The passport was issued so that he could join his father and stepmother in Baltimore, Maryland. In 1850, he returned to Baden to help settle the estate of his maternal grandmother, Johanna Elisabeth (Hoffmann) Förstner, and the passport reflects his arrival in Mannheim.

And why do these papers – very much desired by museum curators with an interest in William Boucher Jr.’s career – keep slipping through my fingers? The reasons, I suspect, will be familiar ones: I graduated from high school in the same year that my mother abruptly moved from Florida to Massachusetts, at which point the Boucher papers disappeared into the chaos of the move. They then resurfaced when my mother died, and I carefully had them conserved. They returned from North Andover in pristine shape, and I set them reverently down … somewhere … and now I can’t find them!

All of which will be a familiar tale to genealogists and non-genealogists alike. The Boucher papers are my version of lost car-keys, or – as I would prefer to think – Brigadoon, and one day soon they will turn up (and be scanned at once – a story for another day, I hope!).

Oh yes, I’ve misplaced family papers too and kick myself throughout desperate searches to find them. They’re here somewhere. My greatest fear is I will die and the kids will throw stuff out without even looking to see what they are throwing out. OK! I’m going to look again. Right Now!

Good idea, Deane. I will be using the snow day tomorrow to do the same!

Scott, when you find your papers, I think you’ll find a lot my lost ones with them!

Yes, Alicia, I think it could also be a “Socks Lost from the Dryer” situation — somewhere there are a lot of unmatched socks…

You’re adorable, Bro.

🙂

Oh my, old story. I actually have bona fide institutional archives lined up for a lot of family stuff, but everything is scattered, interfiled with desk-jet printed Web junk, etc. I keep meaning to set up dedicated boxes for each destination, but . . . This even with a certain somebody in my house warning me that she’s certainly not going to sort through all my stuff.

Scott, you mentioned the papers returning from North Andover; this presumably is the NE Document Conservation Center. Can one, as an individual holder of fragile family papers, actually have work done there? I’d thought it was really strictly for institutions…

Michael, Now that you mention it, I’m not really sure! As I remember it, the NEDCC did the work, but perhaps that’s just where I started looking for conservators. (I have the vague recollection that the whole project took a long time!)

I should note that I was working at NEHGS in those days, so perhaps the work was done for me under that institutional umbrella…

Sounds like a certain family photograph album I’ve not been able to locate for some time! Regarding the car keys, it is not time to worry if you cannot find them; it IS time to worry if you can’t remember for what they are used! 😉

My mother inherited over 200 family letters starting in 1840. I managed to persuade her to donate them to the LSU library Archives for preservation. Earlier, my father had donated papers related to starting his business and her election to the School Board during integration. After her death, all papers, photos, documents were collected from all corners of the 4 generation home and put into the Archives. I know if I kept it, I would misplace or damage it. I have access whenever I need information, but the originals are safe from me.