A few months ago, I was searching for a marriage record in our microfilmed collection of New Hampshire Vital Records to 1900. I was able to find the marriage record between Jonathan W. Winter and Almira Goodhue, dated 5 August 1832 at Campton, Grafton County, New Hampshire. However, the marriage record had some information that I was not expecting: that Almira’s marriage to Jonathan Winter was her second.

A few months ago, I was searching for a marriage record in our microfilmed collection of New Hampshire Vital Records to 1900. I was able to find the marriage record between Jonathan W. Winter and Almira Goodhue, dated 5 August 1832 at Campton, Grafton County, New Hampshire. However, the marriage record had some information that I was not expecting: that Almira’s marriage to Jonathan Winter was her second.

The fact that Almira had been married previously contradicted other information that I had already found. In a land record filed between J.W. Winter, Elmyra B. Winter, and Daniel Goodhue [Jr.] dated 27 March 1848, J.W. Winter and Almira forfeited their share in the estate of a Daniel Goodhue, described as “our late father” in the deed. This indicates that Daniel Goodhue [Sr.] was Almira’s father, and that Goodhue would be her maiden name, not a married one. Similarly, census records indicated that Almira was born circa 1816, and therefore would have been only about sixteen years old at the time of her marriage to Jonathan Winter, a little young for her to have been married twice.

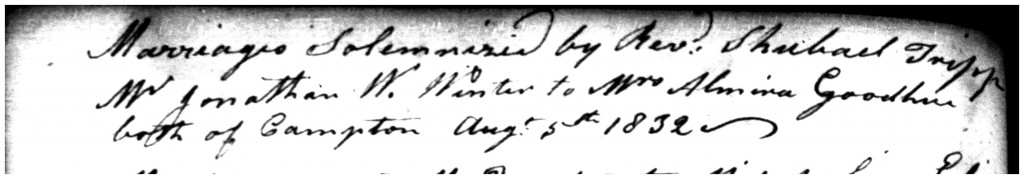

As these records offered different and contradictory information, I turned to the original town records of Campton, which we also have on microfilm at NEHGS. The original town record states that Mr. Jonathan W. Winter married Mrs. Almira Goodhue on 5 August 1832; there is no mention of her being a widow, nor is there any indication that she had been previously married, other than the fact she is listed as “Mrs.”

There is a common misconception that the prefix “Mrs.” on a record automatically signals that a woman has been married previously. An article written by Dale H. Cook on The Plymouth Colony Pages dispels that belief and provides definitions of several other antique usages.

According to the article, “in Colonial times the use of ‘Mrs.’ in an intention or marriage record did not mean that the bride had previously been married. In those times ‘Mrs.’ was the feminine equivalent of ‘Mr.,’ which was originally ‘Master,’ … signifying a person of some prestige in a community, such as a selectman, a minister, or a militia officer, and abbreviated ‘Mr.’ The wife (or soon-to-be wife) of a man entitled to be called ‘Mister’ was sometimes called ‘Mistress,’ abbreviated ‘Mrs.’”

It looks as though, following the town record’s use of Mrs., the individual transcribing Almira (Goodhue) Winter’s marriage record mistakenly assumed that her marriage to Jonathan Winter was her second. This is an object lesson in preferring the original source to a transcription!

For other commonly used colonial phrases and their interpretation, see Cook’s article as well as “Terms of Relationships of Colonial Times,” published by George E. McCracken in The American Genealogist (available at americanancestors.org).

Same use of the term exists in the Medway Massachusetts to 1850 records! It was quite confusing for a while until it dawned on me that it was just the clerks use of Mrs. as an abbreviation for Mistress.

Do you know when that erroneous “2nd” marriage record transcription was made … the one you found in the microfilmed collection of “New Hampshire Vital Records to 1900”? Was is distant in time and/or from the marriage itself?

“… and/or location … ” Sorry for the premature post-click.

The transcription was made on 9 March 1908 by G. Little, the Campton Town Clerk at the time.

Link to Cook’s article doesn’t work. Thanks for the “Mrs.” explanation.

The links are now fixed.

Wow, very interesting article. Did not know that “Mrs.” could likely have meant Master or Mistress. Great information for those researching during those times and stumbling upon Mrs. Thanks for sharing!

I found an image of a 1778 marriage in Dunstable, Middlesex Co, MA, between a Mrs. Lydiah Pike, age 18, and Enoch Jewett, of an adjoining town in NH. He had served with Washington at Valley Forge. At the time I first saw this, I assumed she was a widow, in spite of her youth, but soon learned that her father was Daniel Pike of Dunstable. This had to be another case of a “courtesy” use of the title “Mistress.” In this case perhaps it was because of his service with Washington

Very informative, thank you.

While the explanation of use of “Mrs.” is useful, it does not contradict the possibility that Almyra was, indeed, married earlier — even only months. She could have eloped to marry elsewhere. Annulment or early death, and even divorce of a husband are possible.

Jade, that’s what I was wondering with my earlier comment. If the transcription had been done close in time and place to this marriage, then might knowledge that it was her second have been well known in the community, if not well-documented. (Or not, of course.)

You are correct, an annulment could explain the use of Almira’s maiden name in her marriage to Jonathan Winter. My post was simply to point out the errors that can be found when a record is transcribed, as well as show the antique definitions of particular words that can mislead someone doing family research. I searched the Campton Town Records for a marriage involving Almira Goodhue prior to her marriage to Jonathan Winter, but if she was previously married, she did not marry in Campton, as there is no record of a previous marriage.

Town Clerk (one of the Godfreys, I think) of Taunton, Mass., habitually used “Mrs” as an honorific during the 1730s-1740s, indicating STATUS, just as Goodwife/Goody was often used throughout the 1600s.

The practice was not, however, as culturally wide-spread a usage as “Mr”, so when it appears a researcher’s default is to “huh, had a first marriage”. Have to keep the alternative in mind always.

Also, may be useful in distinguishing between 2 same-surnamed families in a town if one keeps getting the honorifics and the other does not. Which is what I still hope will confirm the correct parentage of “Mrs. Abigail Briggs”.

Thanks for the Dale Cook links. I did not have that bookmarked. Really, Dale needs to be encouraged to have that turned into a half-page filler note for the Register or an illustrated 3 pager for American Ancestry. Putting it on the record.

A rather obvious, perhaps too obvious, explanation is that if Mrs. is used with a female given name, then the term “Mistress” is the probable conclusion. If used with a male given name, a previous marriage is very likely: t.e. Mrs. Anne Smith vs. Mrs. John Smith. If any doubt — well we know the rest……

I have an ancestor “Mrs Hannah Porter: who married John Symonds in Beverly in Jan, 1763. She was 20 years old, and there was no evidence of an earlier marriage.

My notes say:

“From page 109 of John Howland of the Mayflower, Volume 3, it is mentioned that “Mary….was callled “Mrs Mary Childs, a term used for upper class unmarried women…”

Wayne

Excellent point. The family researcher must be careful to not attribute current meanings to descriptive older terms. “Junior” does not mean “son of,” and I have seen the term applied to women as well. “Esq.” or “Esquire” did not indicate that someone was an attorney.

This was very helpful. I came across a marriage record for a woman I thought was my ancestor’s sister. But, it said Mrs. So, then I wondered whether she was really a sister or just someone who had married a man with the same last name as my ancestor. I will go back and look at that record again and do more research. I am trying to find a record of my ancestor’s parents and so was also looking at siblings to see if I could find proof of their parentage.