The legacy of Salem-born author Nathaniel Hawthorne is that of a great American writer, one whose tales of New England life and Puritanism were a focal point of the Romantic literary movement. His 1835 short story “Young Goodman Brown” became one of his most well-known works. Inspiration for this work was derived from a family history that haunted Hawthorne throughout his life and resulted in a number of literary classics that dismiss or re-evaluate this legacy.

The history of the Hathorne family in America begins with Major William Hathorne (1607–1681), a well-known prosecutor of Quaker heretics.[1] Before Nathaniel, the most famous member of the Hathorne family was his great-great-grandfather, John Hathorne, a respected magistrate in Salem. John Hathorne was the third son of Major William and Anna Hathorne. Some of John Hathorne’s titles and positions included Deputy of the General Court (1683), Assistant to the Bay Colony (1684), Magistrate Judge of the Court of Common Pleas, Commander in Chief against the Native Americans (1696), and Judge on the Superior Court (1702).[2]

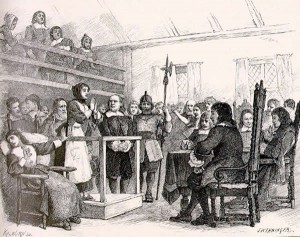

Perhaps his most famous role was as one of the most prosecuting judges during the Salem Witch Trials. According to one historian, “Hathorne’s task was to query the victims about serious accusations in a time when virtually all Christians believed in witchcraft.” A number of people accused of witchcraft – or members of their families – are said to have cursed the judges, and literary scholars suggest that this history was on Nathaniel Hawthorne’s mind when he wrote The House of Seven Gables, a tale in which an established Salem family confronts its ancestral guilt.[3]

Prior to the trials, the Hathorne family had prospered through shipping and farming, and all five of John’s sons turned to seafaring lives. (Today, the gravestone of John Hathorne can still be seen at the Charter Street Burial Ground in Salem.[4]) Nathaniel’s great-grandfather, Captain Joseph Hathorne, was born during the year of the Salem Witch Trials in 1692. During his lifetime the family’s economic position declined, although at his death in 1762, Joseph’s estate inventory included funds in excess of £1,600 and an extensive list of possessions.[5]

Certainly by the time Nathaniel Ha(w)thorne, the author, was born in 1804, the Hathorne family had become less socially and economically prosperous. As a result, Nathaniel’s family was barely able to gather up enough money to send him to Bowdoin College in 1821. By the time he graduated, Hathorne had been convinced by one of his sisters (it is unknown whether it was Elizabeth or Louisa) to add a ‘w’ to his surname as a way to distance himself from the pernicious Hathorne legacy. He found himself fascinated by the ideas of Puritan sin and suffering, concepts which played a key role in his writing.[6]

By writing through this family legacy of inherited sin, Hawthorne created great art. Even if there are not always direct models or parallels for his characters and situations, Hawthorne’s own family history provides a useful prism through which to view his themes and arguments.

Notes

[1] Luther S. Luedtke, Nathaniel Hawthorne and the Romance of the Orient (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989), p. 19.

[2] Margaret B. Moore, The Salem World of Nathaniel Hawthorne (Columbia, Mo., and London: University of Missouri Press, 2001), pp. 37–38.

[3] Ibid., p. 38.

[4] FindAGrave.com entry for Judge John Hathorne.

[5] Moore, The Salem World of Nathaniel Hawthorne, pp. 38–39.

[6] Rosemary Guiley, The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca (New York: Infobase Publishing, 2008), p. 156.

For those of us who enjoy knowing about family history beside the genealogy your background story of Nathaniel Hawthorne is splendid. I lked reading of the effect on him of what his ancestors did in his family.

Among my clutter of antecedents are Judge Hathorne, numerous accusers, several accused, and one executed (John Proctor). Makes research interesting to try to follow contemporary, shifting, points of view. Challenging to try to assess significance of socio-economic statuses (?stati), and ‘otherness’.

Thank you, Zachary Garceau! I very much enjoyed your piece on Hawthorne’s ancestors and his chosen literary themes.