The value of family letters can go far beyond the sentimental, providing important genealogical information on extended family and in-laws that may have been previously unknown. But what if, when attempting to piece together this puzzle of information, you are missing its most basic piece: a surname?

The value of family letters can go far beyond the sentimental, providing important genealogical information on extended family and in-laws that may have been previously unknown. But what if, when attempting to piece together this puzzle of information, you are missing its most basic piece: a surname?

I recently helped a woman who wanted to know the names of her great-grandmother Caroline Ames’ parents. She knew Caroline’s birthdate and that she had grown up in North Carolina, but could not find her on any census record prior to her marriage, creating a road block in attempting to locate information on Caroline’s family.

However, this woman did have a collection of letters that Caroline had written to her maternal aunts. Her letters were filled with references to “Aunt Lizzie,” “Aunt Lill,” “Aunt Maggie,” and “Uncle Charlie,” along with several important clues: the addresses of Caroline’s aunts and the married name of Aunt Lizzie.

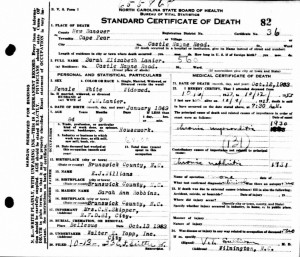

The death certificate of Aunt Lizzie, also known as Sarah Elizabeth Lanier, can be found in North Carolina Death Certificates, 1909-1979. Luckily, Lizzie’s death certificate listed her maiden name: Williams. Though I had a potential surname, I wanted to verify it with the other family members mentioned in Caroline’s letters. Since the addresses of these family members were preserved, I then browsed census records for the address of Aunt Lill and found a woman named Caroline Morill, who seemed like a potential match.

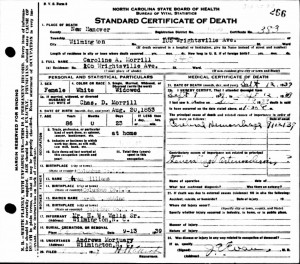

Once again turning to North Carolina Death Certificates, 1909-1979, I located Caroline Morrill’s death certificate, which listed her maiden name as Williams.

Once again turning to North Carolina Death Certificates, 1909-1979, I located Caroline Morrill’s death certificate, which listed her maiden name as Williams.

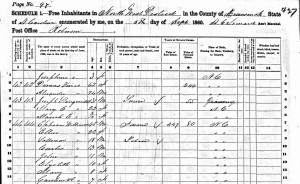

With this new information, I searched the 1850 United States Federal Census for a Williams family with children named Sarah Elizabeth, Caroline, or Maggie. An Ephraim Williams, living in Brunswick County, was married to a woman named Sarah. Ephraim and Sarah Williams had three daughters: Margaret, Helen, and Sarah, along with a son, Charles. Given the information from Caroline’s letters, if “Aunt Maggie,” “Aunt Lizzie,” and “Uncle Charlie” are actual relatives, then that would leave Caroline’s mother to be the Helen Williams, daughter of Ephraim and Sarah Williams and sister of Margaret and Sarah.

The Williams family found in the 1850 Census does not have a daughter Caroline, so I went forward ten years, to the 1860 Census, to see if this family had a daughter named Caroline born later. Ephraim Williams was still living in Brunswick County in 1860. There is an Ellen Williams listed on the census who is approximately the same age as Helen; given how similar the names Helen and Ellen are, they are probably the same person. Sarah, the wife of Ephraim, is not listed on the 1860 Federal Census, so she most likely died between 1850 and 1860. However, the 1860 census does list two additional daughters: Mary, born circa 1852, and Caroline, born circa 1853, the same age as the woman I had thought was Aunt Lill.

The Williams family found in the 1850 Census does not have a daughter Caroline, so I went forward ten years, to the 1860 Census, to see if this family had a daughter named Caroline born later. Ephraim Williams was still living in Brunswick County in 1860. There is an Ellen Williams listed on the census who is approximately the same age as Helen; given how similar the names Helen and Ellen are, they are probably the same person. Sarah, the wife of Ephraim, is not listed on the 1860 Federal Census, so she most likely died between 1850 and 1860. However, the 1860 census does list two additional daughters: Mary, born circa 1852, and Caroline, born circa 1853, the same age as the woman I had thought was Aunt Lill.

Using Caroline Ames’ letters, combined with census records and death certificates, I thought I had found her mother: an Ellen or Helen Williams. With this potential name, I searched North Carolina Marriage Records for an Ellen or Helen Williams marrying an Ames, and came across a marriage record for a David Ames marrying Ellen Williams in Brunswick County in 1861. And with that, we had determined the parents of Caroline Ames.

Great detective work! I love hearing stories about this kind of challenge and such creative ways of finding the solution. I did some similar detective work proving my Mayflower ancestors.

Thanks for your great article! I have a fragile letter sealed with a red substance written in 1847 in Lyman, (now Monroe) Grafton, NH by my 2nd gr grandmother. She signed her letter with her first and married name and listed several family members by first name as well as shared about the prices of some of the crops. I transcribed it as best I could because I didn’t want to keep handling it and have been attempting to investigate each of the names and places mentioned. I have 2 other shorter letters written by her daughter as well. It is the only tangible evidence I found that connects my great grandfather to his parents. I love to read them again and again and seem to find new clues each time. So precious!

Just a suggestion, if you haven’t already done this —instead of repeatedly handling the fragile letter, take a photo of it! Then you can revisit it without worry of damaging the original. What a precious treasure!

Good work, indeed. An example of what can be achieved in short order using the Society’s resources or material accessible through it, Hope the letters or transcripts thereof are attached to the report in the Archives. Remember, fellow members, Make PLANS for Your Stuff!

A cousin had a family letter written to “Dear Uncle James” in Michigan from his nephew in Boston in 1859 which mentioned a “Sister Hannah” and a man named Mr. Richardson who had passed away the year prior, who was Hannah’s husband. The nephew who wrote the letter signed his name, but wouldn’t you know it, there was a hole in the page where his first name should have been! Thankfully his surname appeared and it was Babcock. These few clues allowed me to find the sister of my gr-gr grandfather (James) and eventually two of his siblings. Anyone who has an old letter in the family should not discount the clues that might be there, no matter how remote. It just takes some detective work!

Letters are indeed a valuable resource. My mother saved every letter she received starting the day she departed for college in 1928. They included hundreds from her mother, who religiously wrote her every week. I’ve finished reading those predating her marriage and am currently working those dated 1945 and after. I cannot count the number of my grandmother’s references to vital facts — mostly dates, places and causes of death, but also records of children not otherwise recorded — of relatives that have led me to fill out important information in our tree.

I have a museum studies certicate from Tufts. As part of that I researched some of the quilts at the house museum between Burlington and Middlebury. At the time my daughter was a student at Middlebury so I had dinner with her. The gal that I worked for at the museum published a book that included some of my data.