Jimmy Fallon recently aired his recurring segment, the “Do Not Read List,” which pokes fun at books with unfortunate titles or unconventional subjects. To my surprise, one of the books featured on the spot was the popular genealogical resource, List of Persons Whose Names Have Been Changed in Massachusetts, 1780-1892. Fallon introduced the book with a sarcastic joke: “420 pages of names … changed names. That’s a page turner.” Then, he proceeded to mock those who changed their generic names to something comical.

While I can appreciate his joke, I have to respectfully disagree with Mr. Fallon’s suggestion to avoid a List of Persons Whose Names Have Been Changed in Massachusetts, 1780-1892. Don’t get me wrong, I am not offended by his sarcasm. Any medium that exposes the general public to genealogy is a boost for the field. Instead, the joke renewed my sympathy for those researchers (including myself) whose ancestor changed their names. To only be so lucky as to find your ancestor on one of those “boring” 420 pages!

Why then, did our ancestors change their names? Contrary to popular belief, surnames were not changed at Ellis Island, Castle Garden, Angel Island, or any other immigration station, as often depicted in pop culture (i.e., The Godfather: Part II). Frequently, it was the immigrants themselves who decided a change of name was necessary, and who did so after coming to the United States. They may have changed their names in an effort to assimilate to their new environment, or out of fear of discrimination, or because the surname was difficult to pronounce or spell. For whatever reason, a name change often hinders the progress of even the most seasoned researcher.

To locate a record of a name change that occurred in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, you may want to begin searching for your ancestor in newspaper databases (and on microfilm). While the laws varied from state to state, some courts required an announcement of identity change to be printed in a local newspaper. You could search several different websites that have large collections of digitized newspapers, such as the subscription sites 19th Century U.S. Newspapers (available to NEHGS members here: http://www.americanancestors.org/external-databases/), GenealogyBank, Newspaperarchive.com, or Newspapers.com, or free sites like the Google News Archive and the Library of Congress’ Chronicling America Collection. These modern name changes may also be filed in a regular court with divorce jurisdiction. Again, these collections will vary from state to state.

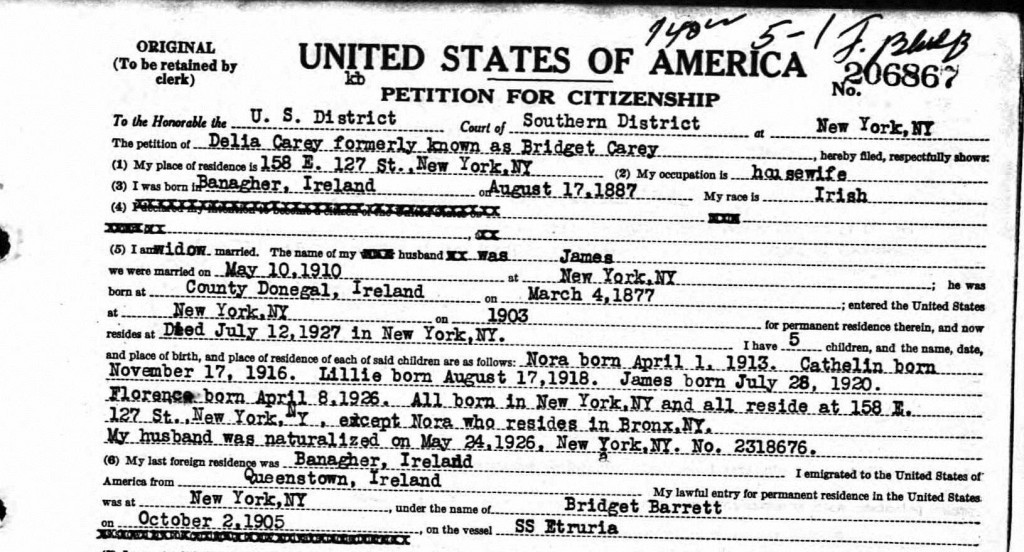

Additionally, naturalization records after 1906 may also provide evidence of a name change. For example, my great-great-grandmother Delia Carey filed her petition for citizenship in 1932. The record indicates that she emigrated from Queenstown, Ireland, aboard the S.S. Etruria on 2 October 1905 under the name Bridget Barrett. Happily, because the record provided this previously unknown name, I was then able to locate her baptism in Ireland and her passenger record in New York City, a feat that would have been impossible had I not located evidence of her name change.

Whew, what a lot of information is contained on this card. Can’t imagine why she’d have wanted to change from Bridget to Delia however, but the last names are the important ones here. However all those children’s names and her husband’s information as well. Important little card:)

My own great-grandmother x2 did the same – our family always called her Delia, but her name when she was born in Ireland was Bridget. Not sure of the origin of the name Delia – perhaps it was a nickname for Bridget (such as the name Peggy is for someone named Margaret which also never made sense to me).

I am forever amazed when people don’t know WHY their parents were given the names they were. There must have been a reason for naming your baby — perhaps a family members name or from a book read or even because it was popular. I was named for Grandmother but no one could tell me why she was named Daisy.

Donna, you are correct! The given name Delia and Bridget are often interchanged in Ireland. But, when I was a beginner to genealogy, I was unaware of this tradition. As a result, I didn’t know to check for Bridget as well as Delia when I was searching for my great-grandmother’s passenger list and baptismal record. Once I found the naturalization record, I was able to locate so much more about her life in Ireland!

Place names and name changes. One of the mysteries in my husband’s lineage is why his great-grandfather, who immigrated from Sweden to northwestern Illinois, changed his name.

His surname was Johnson and when he got to the area of Illinois in which there were a lot of other Swedish immigrants, he was not happy to be one of the many persons with the surname of Johnson. So he changed his surname to Boo! Yes, hard to believe, but there was a reason for the choice of this new surname. When my husband and his sister took there mother to Sweden a few years ago they discovered that the farm hr grandfather grew up on was called Bukara! We think the surname Boo was a direct connection to the place he left behind in Sweden.

The first Piatt came to New Jersey in 1676. His name was originally Rene Lafleur and he changed it to Rene Piatt. No one knows why. There are a several generations of Lafleur on the Isle of Jersey and even a few in northern France.