Josef Izsack’s case in the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) collection only spans one year, but it highlights an interesting tale spanning a longer period than twelve months. Deported after entering Boston as a stowaway in 1946, Izsack came to the United States again the following year, working as an engineer on the Norwegian liner S.S. Fernglen. He was denied the ability to come ashore, though, owing to that previous attempt at entering the United States. An old shrapnel wound became infected and Josef Izsack was forced to spend several months at a marine hospital on Ellis Island.

According to his case files, Josef Izsack had been a passenger on the S.S. Henrietta Szold, which sailed to take Jewish refugees to Palestine; the liner was stopped and forced to land at the island of Cyprus in August 1946. Izsack managed to escape, avoiding placement in the British internment camps set up on the island. Owing to a background in an underground Palestinian group, he was unable to safely return to Europe. Izsack also alluded to being shot and wounded by the Nazis, but gave few other details.

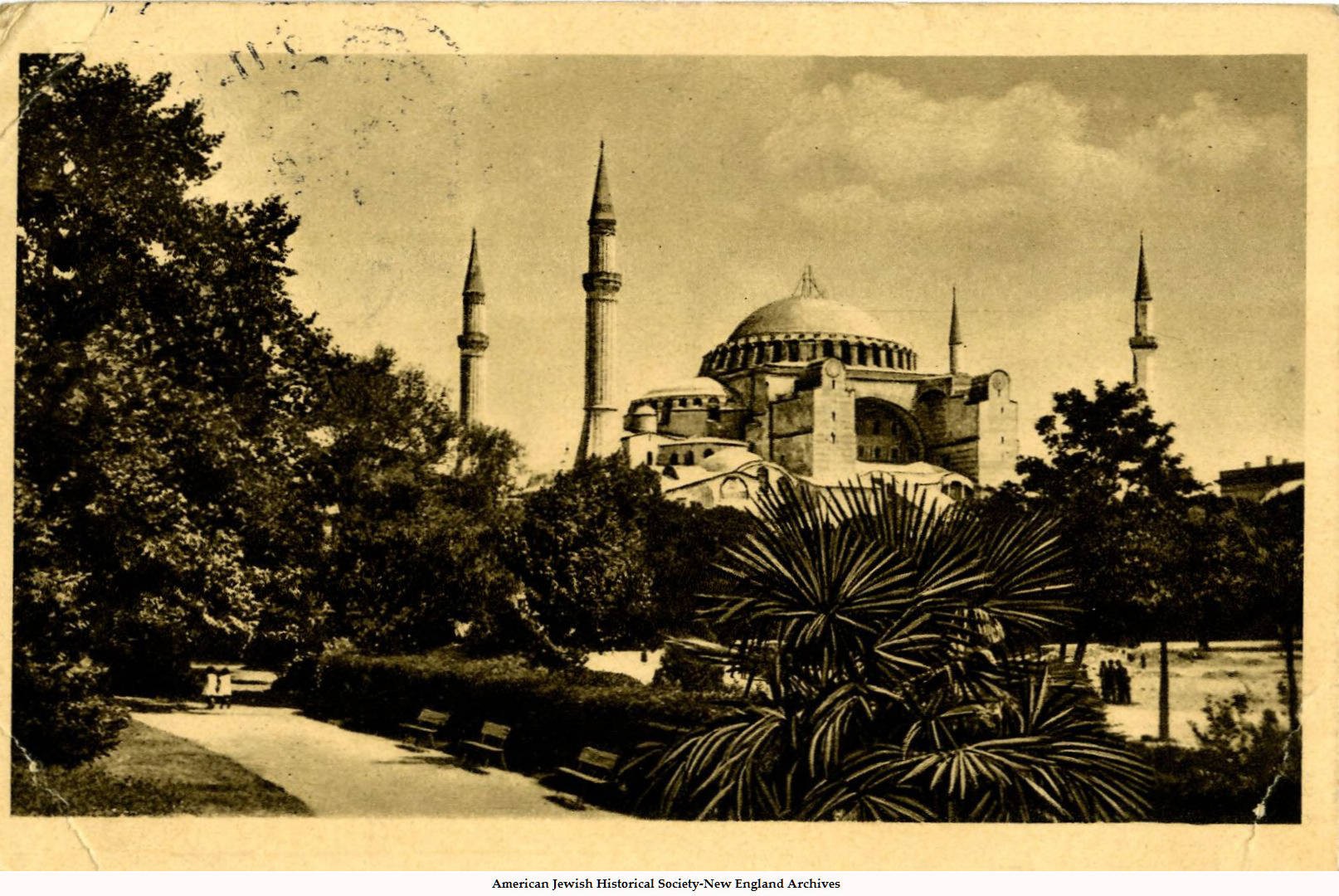

Within a few weeks of his escape from Cyprus, he made his first visit to the United States on board the Fernglen. Identified as a stowaway, he was sent back to Europe onboard the ship, with visits to Lisbon and then Istanbul. By January 1947, he had found a place in the Fernglen’s crew; on the other hand, he was now effectively stateless.

Owing to a background in an underground Palestinian group, he was unable to safely return to Europe.

Izsack’s grandfather visited him while he was in the hospital in New York, but attempts to have him join his grandfather in Canada were unsuccessful; relatives in the United States were only willing to write him affidavits and support him on the condition that he marry one of the girls from the family – which he refused to do. HIAS sought to settle Izsack in a Latin American country, but was unable to do so, despite repeated efforts and motions made to various consuls. At one point, Izsack was interested in reaching Bolivia through an associate, but was told that HIAS could not provide funds for that.

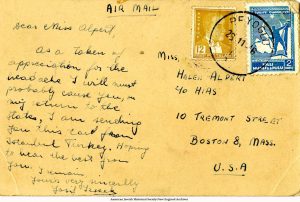

Izsack was less than pleased, and wrote frequently bemoaning the slow pace at which HIAS was operating, and even accused HIAS of actively trying to prevent him from succeeding; Izsack went so far as to threaten to tell people that HIAS was neglecting Jewish Immigrants. His complaints led to a rocky relationship with his HIAS representative, William Neabau, becoming confrontational at times; at one point Neabau gave Izsack “a good lecture” while he was in the hospital. The complaints prompted Neabau to remark that Izsack “is so profuse in his thanks and appreciation when talking to you … but is ready to use a stiletto when your back is turned.”

Under a ticking clock, as Izsack’s stay in the hospital neared its end, HIAS attempted to secure him visas and passage to the Dominican Republic and then Ecuador. The latter was rejected even after Isaac Asofsky swore before the consul that HIAS would take responsibility for Mr. Izsack while he was there, but the consul in New York refused to issue any visas to former deportees from the United States.

Izsack’s letters to HIAS-Boston became increasingly morose: he wrote that “I tried very hard to find a home and forget the past few years, but it just didn’t work out,” and “I do envy those who found death in Nazi concentration camps [sic], they are better off.” Neabau himself commented that “I am very much afraid that we have reached the end of the rope as far as this case is concerned.”

It’s unclear what happened to Josef Izsack after this, and whether he ever managed to find a country to call his home.

The Jewish Heritage Center’s Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), Boston Collection contains the case files and arrival cards of immigrants who received assistance from the HIAS Boston office between 1886 and 1977. Some records also include ship manifests, scrapbooks, passenger lists, photographs, and correspondence between immigrants, sponsors, officials, and HIAS Boston staff.

The case files are available to Special Researchers and NEHGS Research and Contributing Members. To learn more about the HIAS Boston collection, view the finding aid and the webinar, Using the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society Boston Collection. For more information or to request access to this collection, please email jhcreference@nehgs.org.

To learn more about Jewish Heritage Center and its collections, visit the website.

Well written, informative and timely. Thank you.

A very interesting story…and go Beavs!

Being stateless is a frightening experience. A friend, Chinese by birth, who grew up in Malaysia during WW II, was sent to the US for her education, as was the man she ultimately married. They were told, incorrectly, which US customs office to apply for naturalization through. After they finished their PhD studies, they moved to get professional jobs, informing that customs office. They weren’t told that now they needed to transfer to a different customs office, closer to their new home. As the date for their naturalization came nearer, they were finally told they had to begin the process all over again. Worse, the country of Malaysia no longer existed. They were stateless for almost a decade, afraid they would be deported with nowhere to go. The story ended well, with them becoming US citizens, but they had lived with that fear for years, afraid to travel outside the US for professional meetings and to visit family. They didn’t realize how frightened they had been until the day they went through the naturalization ceremony and were finally citizens.