In the first year of Kenny and Alice McLean’s daughter’s life, labor strife at the Telluride mines was affecting the community.

On 1 September 1903, difficult and scary times came to Telluride. Union members demanding an eight-hour rather than a twelve-hour workday walked out of Telluride’s ore processing mills. This shutdown caused the closing of area gold and silver mines. When the Tomboy gold mine tried to reopen with nonunion workers (strikebreakers or “scabs”), the union posted armed picketers to prevent the new workers from entering.

On 26 November, the Telluride Journal reported that local law enforcement disarmed and arrested five men at the Tomboy for “making riotous demonstrations.” The paper continues: “The men were hog-tied, their arms being fastened close to their legs by ropes about the wrist, then they were tied together and the rope attached to Deputy Runnells saddle horn, and in that way they were marched down the trail.” When their union president came to the jail to talk to the men, he was also arrested and “put with the bunch, where he can talk to his heart’s content.”

On 26 November, the Telluride Journal reported that local law enforcement disarmed and arrested five men at the Tomboy for “making riotous demonstrations.” The paper continues: “The men were hog-tied, their arms being fastened close to their legs by ropes about the wrist, then they were tied together and the rope attached to Deputy Runnells saddle horn, and in that way they were marched down the trail.” When their union president came to the jail to talk to the men, he was also arrested and “put with the bunch, where he can talk to his heart’s content.”

At the request of mine owners, Colorado National Guard troops were called in to help keep the peace. In a letter to Kenny’s sister Christine on 3 January 1904, Alice laments that it didn’t seem at all like Christmas to her because of the strikes, saying “all the miners working here now are from the outside. . . The soldier boys have been here for a month or two . . . and nobody can go to the mines without a pass.” Local deputies took to arresting striking miners for vagrancy. Once the mines were successfully operating with imported nonunion labor, the troops left Telluride in January 1904.[1]

It seems the bad feelings over the labor wars did not die quickly. A year later, in early December 1904, the Telluride Journal reported on Kenny taking care of business in wild-west style: “Among the returning exiles is John Conn [one of the men arrested during the strikes], a Finnlander prominent in the palmy days as proprietor of a blind pig whiskey joint in the basin, an alleged fence for ore thieves, and busy agitator.

“Sunday night he met an honest workingman and abused him like a horse thief for working for a living . . . and declaring that as soon as Adams is inaugurated that all the scabs will have to leave this camp. Night Marshal McLean heard of it and looking up Mr. Conn yesterday morning interviewed him as to the truth of the report. The anarchist did not deny it and proceeded to give the Marshal some of his lip reiterating his threats against scabs. When Kenny got through with him Conn’s eyes were in mourning and his face is hardly recognizable by his most intimate fellow agitators. The Marshal then warned him if he heard any more of his threats calling people scabs, etc., yesterday’s punishment wouldn’t be a marker to what he’ll get. This system has its advantages over giving the disturbers a free ride out of the country or even letting them walk out unmolested.”

In late December, the paper was able to report on a happy event, the birth of Marshal McLean’s son, my Great-Uncle Fred: “Mrs. Kenny McLean presented her liege lord with a Christmas gift at 8:30 this morning, in the shape of a little son. Dr. J. Q. Allen, master of ceremonies, says the youngster is a fine specimen and all are doing nicely.” A few months later, there was more good news: on 4 April 1905 Kenny was elected City Marshal, which meant no more night duty – something that Alice believed was the cause of the stomach problems he’d been having over the last year or two.

A harbinger of the sad times to come ran in the 20 April 1905 paper: “Kenny McLean has been unfitted for the work of patrolman for the past two nights by sickness.” However, things seemed back to normal a few weeks later: “Mrs. K. A. McLean, her daughter, and son, Chief of Police, Jr., went down to Dolores this morning on the Durango train for a visit with Mr. and Mrs. Fred Pheasey [Alice’s brother and sister-in-law]. Kenny has promised to be good while they are away.”

In May 1905, Kenny seemed quite fit for duty: “Chief of Police McLean took in a fellow last evening for making a race course out of Main street. He had a livery horse going at the top of his speed down the street and into [the] J. W. Rogers stable where the horse belonged and where the man fell into the hands of the officer. Kenny gives it out cold that this business must stop, and any one who thinks different can be put right by simply trying the scheme.”

Continued here.

Note

[1] Colorado Labor Wars, Telluride strike, September 1903; Carrol D. Wright, “A Report on Labor Disturbances in the State of Colorado,” Senate Document No. 122, 58th Congress, 3rd Session, 1905.

“Great-uncle”? Or is he a granduncle?

Sharon’s grandmother’s brother is her great-uncle. Grand-uncle is sometimes used, but it becomes awkward when considering great-great-uncles and -aunts.

This is an area that needs addressing on several fronts, one of which is consistency: First, how do we spell granduncle and grandaunt, with a hyphen? If so we then need to spell “grand-father” and “grand-mother” as such which we don’t. Second, if we improperly call a sibling of a grandparent a “great aunt or uncle” it implies a missing generation. I’ve personally been thru this, looking for the missing generation that didn’t exist. In the 1600’s kinship terms were loosely used, creating conumdrums as to relationship. In the 21st century we ought to be doing better, and realize and publish as such that a great uncle is a sibling of a great grandparent, not of a grandparent.

Ross, peevishly

Thanks for the story – very interesting. Those were rough and tumble times!

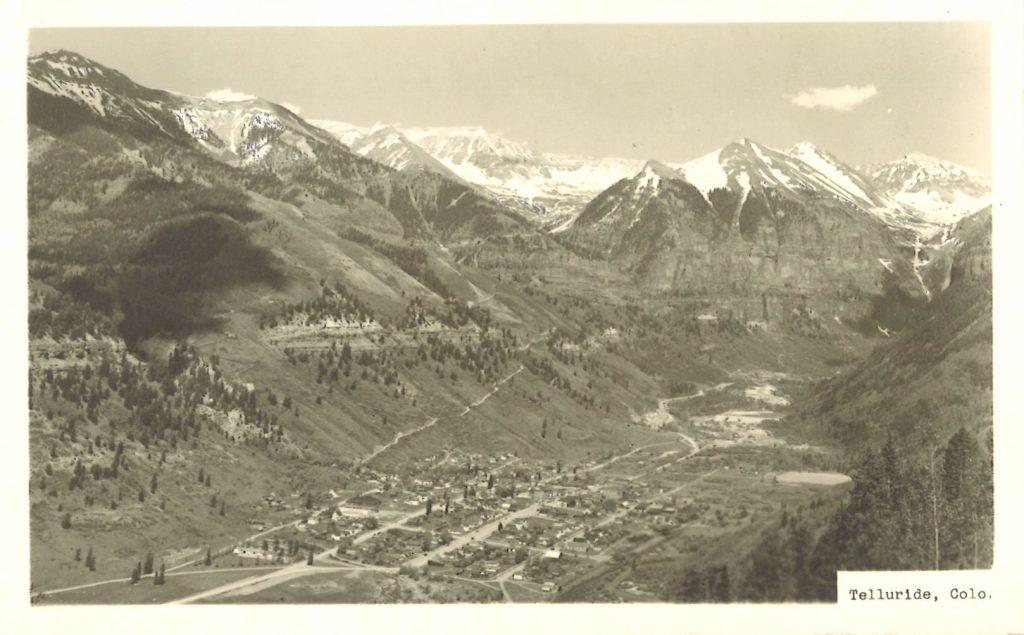

I visited with my husband and kids about 10 years ago. It is a very different place now. Trendy shops and skiing and film festivals. What was the Cosmopolitan Saloon is now an art gallery.