Following up on my post last month regarding Revolutionary War pensions that can have troves of information, I remembered another subsection within Civil War pensions that are almost always filled with immense amounts of genealogical and biographical data. These are the “Parents’ Pensions.”

While most of us are probably familiar with veterans’ and widows’ pensions, the parents’ pension was claimed by one or both of the parents of a deceased Civil War soldier. The pension act of 27 July 1868 stated:

That the laws granting pensions to the hereinafter-mentioned dependent relatives of deceased persons leaving neither widow or child entitled to pensions under existing laws, shall be so construed as to give precedence to such relatives in the following order, namely: First, mothers; secondly, fathers; thirdly, orphan brothers and sisters under sixteen years of age, who shall be pensioned jointly if there be more than one: Provided, That if, in any case, the said persons shall have left both father and mother who were dependent upon them, then on the death of the mother the father shall become entitled to a pension commencing from and after the death of the mother; and upon the death of the mother and father the dependent brothers and sisters under sixteen years of age shall jointly become entitled to such pension until they attain the age of sixteen years, respectively, commencing from and after the death of the party who, preceding them, would have been entitled to the same: And provided further, That no pension heretofore awarded shall be affected by anything herein contained.

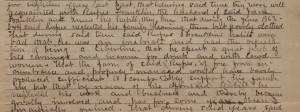

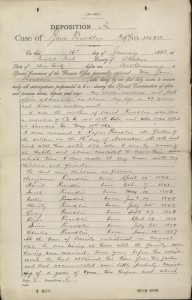

Essentially parents, and in some cases minor siblings, had to prove dependence on the labor of the deceased veteran who died unmarried without children. The most interesting example of a parents’ pension I have found was for my great-great-great-grandmother’s first cousin David Franklin (1841-1864) of Steuben County, New York. David was killed at the battle of Rasaca in Georgia, unmarried and with no children, and so his mother was a candidate to receive such a pension. The interesting thing in this case was that his father was alive but separated from his mother, and living in the poorhouse. The details of David’s father Rufus Franklin’s life were colorfully detailed by several affidavits describing his depraved habits as “bad [in] that he was an inebriate and had the reputation of being a libertine, that he spent a great part of his earnings and income for drink and with lewd women.” (This statement comes from the son of Rufus’s sister, with many statements confirming his bad character from several members of his family.)

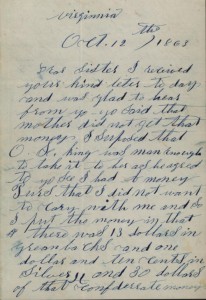

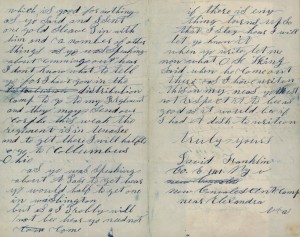

For this reason, the pension is filled with many juicy details, and provides a lot of genealogical information about a fairly poor family in western New York otherwise left out of the records. The pension goes on for nearly 300 pages, including letters David wrote home to his family from Virginia; a deposition giving his parents’ marriage date and names and birth dates of all of his siblings; and an interesting index of witnesses who provided testimony, indicating their reputation as excellent, good, fair, or “not very reliable.”

Ultimately David’s mother Jane received the pension until she died in 1888 and then David’s father Rufus was allowed the pension until his death in 1894. If not for their son’s service, their own tumultuous relationship, and the benefits of a parents’ pension, such details of their lives would likely never be known.

Note

Further information on this family may be found in Christopher C. Child and J. Kelsey Jones, “Family of John and Esther (Daggett) Franklin: A John Billington Line,” Mayflower Descendant 60 [2011]: 158-78.

Thanks Chris. I will look for the parent files. So many soldiers died. Visiting the National Archives has been so worthwhile for me.

I have one of those voluminous scandal filled pension files, too. The soldier was a bad character, and agents of the pension department tracked him relentlessly across NY, documenting his infidelities — naming names. He had deserted twice and rejoined without apparent consequences.

Wow! Thanks for such a colorful reminder. I take it these pension applications are not a separate record group? These would appear under the soldier’s name with a card notation saying “Parents App.”? So getting around to checking for a pension application for any soldier in a family might be a good idea, on the off-chance theory of things, eh?

My great-grandfather’s pension application includes the documentation for the widow’s application, which confirmed what I had already turned myself inside & out about among the Society’s stacks: the minister who married them had NOT submitted their marriage record to the Providence RI city clerk. She documented the train trip from CT and who she hunted down to get signed affidavits from, plus submitting a certified copy of the marriage scroll they had kept with the minister’s signature. 30 years after the event!

[Charles B. Paine (private, 7th Mass. Inf., 1861-1864), of Mass. and Bridgeport CT, m. in Providence with Georgianna Spinney; both were working there in nail factories. GS had spent almost all of the war doing the same job in Taunton factories. Which is where she met Charley’s sister Johanna Harlow Paine who invited her to Taunton’s Welcome Home 7th! party on the commons. And that was that, said my grandmother Emily.]

I have three pension files for my great grand fathers, and although I found many heart-wrenching descriptions of their illnesses and decline in health I did not find what I was really looking for- why did Jacob Sawyer abandon his family in Limington, Maine and go to northern Maine eventually having a second family ( and wife whom he eventually married 5 years after the 1st wife’s death). Well, at least I now know the answer is not there and I was not mistaken that this happened. Overall a great resource!

This is totally fascinating, even though it’s a record of a lot of suffering for his wife and no doubt the other children.

I don’t have a direct ancestor who served in the Civil War. But a collateral ancestor did, who in the 1880 census is listed as “insane.” His father’s will carefully protected the family real estate from this guy, making sure it went to more stable sons even though they were younger, and leaving him only minor property (beds, clothing). One of his descendants has told me horror stories that have come down in her branch of the family. Some of this may actually be documented in his pension file, if we, go looking for it. “Insanity” after the Civil War might well have been what we know as PTSD.

Suki…. In researching my families of the Limington area (Strout and Staples) I found that many of the men of that area went to Northern Maine to do logging. Jobs were few and far between and the mills in the region were not doing well. The term hardscrabble is often used for the employment situation in that area. Even families that owned land were reduced to sending sons to do logging. Many got “western fever” and took their families west to better land, as mine did.

You hit an important spot with this essay. I discovered that one of my g-g-grandmother’s brothers who served in the Civil War died in South Carolina and their mother claimed a Mother’s Pension. It was a wonderful treasure of information and filled in many empty areas in my DAR application and genealogical files. I would suggest that this is a great and significant avenue to use in research.

I sent for my second great-grandfather’s Civil War records a number of years ago. We always knew he was honorably discharged on account of disability in 1862, having served about 14 months, but what was the cause of disability? Could it have been a rebel bullet? A cavalry saber slash? Alas, nothing so glorious or colorful. According to his pension file, he suffered from a hernia “the size of a hen’s egg”, hemorrhoids “the size of chestnuts”, and varicose veins “the size of a pencil”! I suspect it was the first named malady that ended his army service. No wonder the biographies were not specific about the nature of his disability!