Family Tradition versus Fact, and a few shades of Gray

One story often repeated in my family concerned the mystery of my grandfather’s uncle, Morris Larned Healy, who reportedly had died of “lead poisoning” at a bordello in New Orleans . . . or Atlanta. My grandfather, who told the story, was known for his vivid imagination, so I decided to see if the story had any validity.

Morris Larned Healy was born at Dudley, Massachusetts, 22 February 1875, son of Lemuel and Elizabeth Eaton (Larned) Healy. I can find him in the 1880 census, with his parents in Dudley, but in no later censuses. According to Healy History Revised,[1] Morris Healy died in Atlanta, Georgia, 28 September 1909, was buried at Dudley, and was married, with no children. I also found a record of Morris L. Healy getting married in Boston, Massachusetts, on 11 January 1910—four months after his supposed death—to Milla E. Clark, born Milla Eliza Kendall, at Townsend, Vermont, 21 April 1870, daughter of Amos Gould and Gertrude A. (Bruce) Kendall. Milla was first married to Norman F. Clark, by whom she had two children; they divorced in 1902. Her marriage to Morris Healy in January 1910 listed this marriage as her second.

In the 1910 census, however, Milla is still listed with her first husband’s surname, living with her widowed mother, Gertrude. Morris Healy is nowhere to be found. Even stranger, Milla gets married for the third time in 1915 in Leominster, Massachusetts, to Edmond Metcalf, but she is using the name of Milla E. Clark, and still claiming this is only her second marriage! What happened to Uncle Morris?

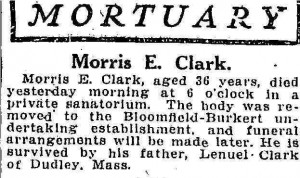

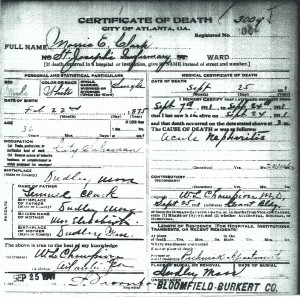

Healy History Revised had claimed he died 28 September 1909, but his tombstone in Dudley shows he died in 1911. Perhaps the genealogy got the year wrong, and he died 28 September 1911. I checked the Webster Times, the newspaper of Dudley’s neighboring town, for funeral announcements in the fall of 1911. There I found a notice for funeral services for Morris Healy at his parents’ house October 5, which mentioned that he died September 24. I then checked the Atlanta Constitution for fall 1911, and on September 26, I found the mortuary notice for Morris E. Clark, aged 36, who died the previous day at a private sanatorium, survived by his father Lenuel Clark of Dudley, Mass. This is partly why Morris has been so hard to find: he was using an alias. Perhaps he used the surname Clark as this was the last name of his wife when he married. His death certificate from Fulton County, Georgia, listed him as Morris E. Clark, with his correct date and place of birth, and as the son of Lemuel and Elizabeth Clark. His cause of death was acute nephritis that lasted two weeks. So much for “lead poisoning”!

I cannot find what happened to Morris’s wife after her 1915 marriage to Edmond Metcalf. Of her children, her son Guy Norman Clark was in the Windsor County Jail at the time of the 1930 census. Guy’s wife, Sarah Elizabeth Castor, was the daughter of Louis Castor, a man convicted for uxoricide, for the murder of Sarah’s mother! Several of Sarah’s descendants, as I have traced them over several generations, have met untimely deaths, which have opened up a whole new series of stories to tell when anyone asks, “So what happened to Uncle Morris?”

Addendum: Thank you everyone very much for the comments regarding lead poisoning as cause of acute nephritis. The implication my grandfather was going for was that this was a “lead bullet,” so perhaps there was some basis for his embellishment. I should also point out that my grandfather was born five years after his uncle Morris died.

Notes

[1] Ethel Eliza Pearl Brown Carrier, Healy History Revised (privately printed, Longmeadow, Mass., 1968), 34.

I think you have the makings for a great historical novel if you fabricate the missing information for each character!

I heartily agree!

Great job, Christopher! I’m sure you’re feeling quite satisfied at finally finding out what happened to Uncle Morris.

Actually, I did a quick google search and nephritis can be caused by lead poisoning, so your grandpa may have been right!

I, too, found that same information, Toya. Kidneys take the brunt of many toxins that enter our bodies.

Poor Uncle Morris. No wonder your grandfather gave him a new ending. I’m glad you were able to find him, though, and solve his mystery. The two stories of his death have an air of pathos about them. Perhaps in a magical way Uncle Morris is in that bordello yet, enjoying himself in a way that seemed to have escaped him in life. “Lead poisoning” doesn’t carry over into the spirit world, so I’m told anyway.

And what a wonderful example of creative and tenacious researching you gave in telling this story!

nice piece of research, Chris

A fascinating bit of research. Thank you for presenting this.

It seems, however, that prolonged exposure to lead is a cause of nephritis.

This CDC document (“http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/csem/csem.asp?csem=7&po=10) says: “…continued or repetitive exposures [to lead] can cause a toxic stress on the kidney, if unrelieved, may develop into chronic and often irreversible lead nephropathy (i.e., chronic interstitial nephritis).”

This association appears to have been made as early as 1904: (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1558679/pdf/amjphnation00916-0097b.pdf): “As far back as 1892, Turner called attention to juvenile nephritis in Brisbane children. The subject was subsequently related to lead poisoning by Gibson in 1904.”

“

On pages 233-4 of this July 1911 edition of the Bulletin of the Bureau of Labor (Vol 23, No. 95), which devotes 282 pages to industrial lead poisoning and worker exposures, is a claim that physicians often did not list lead poisoning as the cause of death. “In Illinois it was said that a certificate bearing the diagnosis ‘acute lead poisoning’ would bring the case under the jurisdiction of the coroner and therefore physicians avoid this expression and instead write ‘acute gastro-enteritis’ or ‘acute nephritis’ etc.”

Here’s the URL to the previous source, which was apparently dropped when I submitted the comment: https://books.google.com/books?id=sKYnAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA234

Thank you very much for these links! The implication my grandfather was implying was a lead bullet, but perhaps there was somewhat of a basis for his colorful description

Well done, Christopher! I’ve spent many years unearthing the real facts in “strange” family stories, but none as exciting as yours. The best I’ve done is 1) prove my grandson and his male ancestors were NOT named after a racehorse, 2) that a distant cousin was NOT the twin of her half-sister born 3 weeks later but a product of incest, and 3) that 20-something husbands who father three or more children in quick succession then “die” can usually be found very much alive in another county or state with a new family.

That said, I agree with the poster who suggested turning Uncle Morris’s story into a page-turner of a novel by slightly altering the facts. It wouldn’t take much altering, since Morris certainly led a life that very well could’ve ended with a chunk of lead delivered by a handgun or rifle!