When I first began researching at the NEHGS Library, I was drawn to the wide array of cemetery records that could be found in published books and donated manuscripts. It’s not by choice that I spend time locating cemetery records; it is because many family members had the ‘misfortune’ of living in New York State, where, outside of New York City, vital records registration did not start until 1881. Instead of using cemetery records to supplement birth and death dates, they often represent the only vital information on my ancestors.

Before the advent of findagrave.com, JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry, Interment.net, or billiongraves.com, one hunted for cemetery inscriptions the old-fashioned way – by spending hours looking through library catalogs using search terms such as “inscriptions/epitaphs/cemeteries” paired with a town/county/state. It was a long process, but not without success, especially given the NEHGS collections.

I often wondered how the Society came to acquire so many cemetery inscriptions, some dating back to the 1880s. Since a “Committee on Epitaphs” was mentioned by authors who submitted transcriptions, I sought out NEHGS Archivist Sally Benny, who hunted through annual reports and Council proceedings until she located the records.

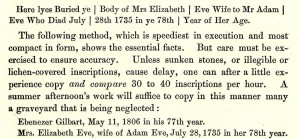

In March 1899, the NEHGS Council voted that a Committee be appointed “…to whom shall be referred the whole matter of the preservation of inscriptions in the ancient burial places of New England…” The Committee on Epitaphs began work that year, recruiting Society members “to arouse local interest” in copying the memorials, at the same time establishing basic guidelines for proper transcription. Manuscripts began to flow in, yet by 1903 the Committee was already looking for ways to quicken the pace: “While everything on the stone is valuable, names, dates, statement of the social relation, mortuary verse, decorations, and even the stone cutter’s evident errors; yet the copying of everything, delightful and fascinating though it is, takes time, and for lack of time many stones remain uncopied and the inscriptions in danger of being lost through the destruction of the stones.”

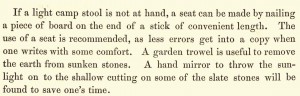

To that end, in 1904 a four-page Circular was prepared offering three methods for copying gravestones, “the choice depending on the skill and patience of the copyist.” Four hundred copies of Suggestions as to Copying Inscriptions were distributed to NEHGS members and allied organizations in an effort to standardize and speed up the transcription process.

Some of the helpful hints in the Circular still ring true today:

As one who continues to make use of the Society’s collection of cemetery records, I now know who to thank for the abundance. I salute the NEHGS Committee on Epitaphs who, 115 years ago, had the foresight to begin the effort to document and preserve these records.

Ah, New York … the giant black hole of genealogy. I have the misfortune of having nearly all my relatives from the early 1800s on in this beautiful but frustrating state, and yes, cemetery records can be all that is available for some of them. It’s one of the reasons I photograph cemeteries for Find a Grave.

Unfortunately, in this area (near Rochester, New York) the old stones are often made with a very soft, porous stone that even with mirrors and a comfortable seat, transcription is nearly impossible without aid of other techniques. The method I employ the most frequently is foiling — using very lightweight (read: cheap stuff bought at the dollar store) aluminum foil set over the inscriptions and tapped into the old lettering with a soft paintbrush. Sometimes this doesn’t even work, but it can be a nearly-magical, totally non-invasive technique for bringing up otherwise illegible inscriptions. The only stones this doesn’t work on are those few that are so unstable on their bases that even touching them might send them toppling over.

And better than a hand trowel for removing sod from near-buried stones: a silicon pie server made for nonstick pie tins. It has a useful triangular shape with a pointy end, one edge made for cutting pie crust, and it’s made not to scratch delicate surfaces. Still use with caution, but it’s much less likely to damage the stone while you’re trying to unbury an inscription.

But like with all records, one must be careful. My grandfather’s tombstone and cemetery record has the incorrect date for the year of his death and we don’t know how that happened.

A great grandfather’s cemetery records say he was a Confederate soldier … a to9tal fabrication based on his claim.

Foiling! What a great idea! @20 years ago I was in Oxford and Guilford NY trying to use white shaving cream and a squeegee. Rain was coming, good, as I was up on a hill and had no bucket of water to wash the stones…but it started to snow! I found Asa Sherwood’s stone and SAR badge but not his father, John. Old records have him there, but he died on a British prison ship and was probably thrown overboard. How to correct this error? And his name isn’t listed on the monument for those men, either. Asa’s younger brother, Levi, is my ancestor, but his house and tombstone are also gone. Curses, foiled again!

I think the flyer is a great idea. If there are any still available or any thought to reproducing them, I would like to have at least one with permission to reproduce and hand out to our Society.

How those people a hundred years ago would love a digital camera. Can’t beat it except when the stones are really old.